Figure in the Frame

The exhibit 'Arnold Newman: Masterclass' gives us all a lesson in the power of the photographic portrait

Reviewed by Katherine Catmull, Fri., March 15, 2013

Portraiture: It's a curious no-man's land where art and commerce can cease hostilities, sometimes even be besties for once in their mistrustful lives. In the heyday of the great oil portraits – and that's been quite a while, as you may have noticed – patrons with pocketsful of cash managed to order up exquisite and eternal pieces of art.

In the 20th century, the two masters of photographic portraiture were Richard Avedon and Arnold Newman. Avedon stuck to the studio, photographing his subjects under controlled conditions against clinical white backgrounds. But Newman entered his subjects' own domains and composed visual poems made of environment and subject, of line, shape, and shadow.

You've probably seen Newman photographs. His portraits of artists, scientists, composers, businessmen – even a notable war criminal – studded Life, Holiday, Look, and other mid-century magazines. His Picasso – hand pressed to face, one eye in shadow – is iconic. His grainy, disheveled Marilyn Monroe is heartbreaking. His portraits manipulate the subjects' own environment to work on every level: emotional, symbolic, and aesthetic.

Newman's remarkable portraiture is the focus of "Arnold Newman: Masterclass" at the Harry Ransom Center. Curated by William Ewing for the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography, this is the first Newman retrospective since his death in 2006 at 88. The 200 framed prints include 28 from the HRC's extensive Newman collection, and for the exhibit's first American stop, HRC Senior Research Curator Roy Flukinger has supplemented them with other selections from its Newman archives.

Newman studied painting at the University of Miami, but money problems forced him out of art school and into his first real job: taking photos in a Philadelphia department store at 49 cents a pop. It was a tough, purely commerce-oriented apprenticeship. In the marvelous Masterclass companion volume, Ewing tells of Newman suggesting that a family group be "lit like Frans Hals." That went over about as well as you might imagine. "Don't try to be an artist," barked his boss, "just take the pictures the way we tell you."

But on his own time, Newman ignored that terrible advice, roaming the streets of Philly with other young photographers who were influenced by the documentary work of Walker Evans and other photographers of the Farm Security Administration. His love for painting, especially abstract expressionism, was now expressed through abstracted photos of buildings and landscapes.

Although Newman ran a Miami portrait studio from 1939-41, he made frequent trips to New York to take photos of those same contemporary artists in their studios, merging portrait photography with his more abstract building and landscape photos.

Those photos of artists in situ became a December 1945 solo show at the Philadelphia Museum called "Artists Look Like This." It was a turning point for Newman. By that February, both US Camera and Life ran stories about his work, and he was on his way.

"There are many things that are very false about photography. You must recognize this, and build on it, and then maybe you'll have art." - Arnold Newman

Newman was commited to getting the print he wanted by any means necessary. "Photography is one percent talent and 99 percent moving furniture," he said, and he never hesitated to rearrange a subject's setting with precision and intent.

He was equally bold in the darkroom, and with permission from the highest authority: photographic pioneer Alfred Stieglitz, who Newman met in New York. Though Stieglitz was, says Ewing, "a famous curmudgeon" who "could be heartlessly cruel to those who sought his approval," he encouraged Newman. The young photographer asked Stieglitz whether commercial-style retouching was legitimate in his more serious photography (specifically, "Can I retouch my relative's pimple?"). According to Flukinger, Newman "said [it] was like going to the Pope and asking for dispensation before you go out and commit the sin. But Stieglitz, to Arnold's surprise, said, 'Whatever you have to do to make the final print. It's the final print that counts.' ... So that became [Newman's] dictum throughout his life."

Newman's cropping could be almost crazily, thrillingly bold. Take what is arguably his most iconic image, his portrait of Igor Stravinsky. The composer sits behind a black grand piano, face propped against his hand. The curving black piano lid towers over him like an enormous, backslanting musical flat. The photo is radically cropped, so that the piano is only a thick black line at the bottom of the frame, and Stravinsky himself a small figure at the bottom left, whose tiny angled elbow mimics the enormous, angled lid. As the wall text says, the portrait "would not have a fraction of its power without the stringent crop."

Newman also played with tonality, as in his simple, abstract, and spectacular photo of modernist architect I.M. Pei. The photo consists mostly of a vast, deep blackness, broken by three ovoid lights that float near the top of the frame like flying saucers in deep space. Across the bottom right frame juts a single pale rectangle, through which peers Pei's impish, bespectacled face.

Flukinger notes that Newman also "did his homework" on subjects. Thus, on the one hand, the avant-garde 12-tone composer Pierre Boulez is framed by sharp lines and angles; while on the other, trees are reflected in the sliding glass door of Ansel Adams' home, and in Adams' eyeglasses, so that he merges with the natural world. The high-energy American choreographer Jerome Robbins splays forward on a stool, limbs spread in all directions, while the classical British choreographer Frederick Ashton is framed as a single vertical line, standing straight beneath a column of black cloth, only his angled umbrella providing witty relief to the perpendicularity.

Newman told a student that his "primary artistic influence had always been Vermeer," that master of environmental portraiture. And yet Newman disliked that term, thinking it "very restrictive," Flukinger explains. "To him, a photograph was more symbolic than environmental. He said 'environmental' sounded more like a document, and he wanted to let people know he was seeing symbols, seeing rhythms, seeing tones, seeing combinations and juxtapositions that all went into that final compilation of an image." No matter how small the figure in the frame, "the person was the important subject. The picture was about them."

Also key to Newman's masterful work is the fierce and unexpected emotionality of his portraits – not only his subjects' affect but his own, as seen in two photos of key figures from the Holocaust. (Newman was a Jew and a strong supporter of Israel.)

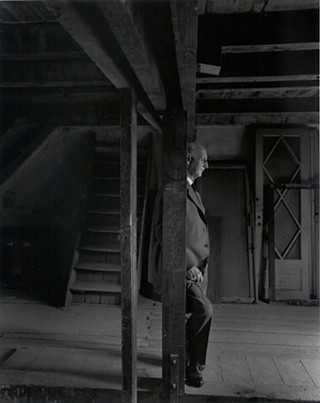

In 1960, at the dedication of the Anne Frank house, Newman photographed Otto Frank in the attic where he had lived with the wife and daughters who died in the camps. Frank is pictured in profile, in half-darkness; he leans against a wooden post, head down, fist loosely clenched. It is a portrait of exhausted, unassuageable grief.

In 1963, Newsweek commissioned Newman to photograph Alfried Krupp, the German industrialist who spent three years in prison as a war criminal for using Jewish slave labor in his factories. (How's that coffee taste now?) Newman reluctantly agreed, but he kept looking for the shot that would express his abhorrence. When he asked Krupp to lean forward between two side lights, his subject's face became dark and demonic. That is the dramatic, disturbing shot Newman chose. "I want my statement about Krupp – I want it known," he said.

The exhibit is called "Masterclass" in part because Newman liked teaching and took on students as assistants over the years. (Examples of his precise instructions, scribbled in red on contact sheets throughout the exhibit, are fascinating and telling.) But it also uses HRC archival material to turn viewers into learners. Beside his portrait of the composer Aaron Copland is Newman's contact sheet with three other, near-identical Copland poses. Why did he choose this pose for his final print? Is it the pose I would have chosen? It's when you begin to think about why Newman made the bold and original choices he did – and why you make the choices you do – that you begin to learn something about portraiture.

These days, we're all photographers, even if only on Instagram. You may be surprised at how this exhibit changes the way you frame your iPhone photos, makes you think about the lines and shadows behind the birthday girl in the family pic. Even amateurs can learn a lot from a master class.

"Arnold Newman: Masterclass" continues through May 12 at the Harry Ransom Center, 21st & Guadalupe, UT campus. For more information, call 471-8944 or visit www.hrc.utexas.edu.