Don't Stop Thinkin' About Tomorrow

Norman Bel Geddes didn't – and we're still dreaming about his future

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., Nov. 2, 2012

Yeah, yeah, everybody wants to know where the flying cars are.

Now that we've reached the future – at least as it was measured by the imagineers of yesteryear – we ought to have jetpacks and robot butlers and food replicators and all the other fantastic gadgets and mechanized marvels they dreamed up, including those winged jalopies that'd let you zip on over to the H-E-B by air as easily as by road. So where are they?

Well, I'm sorry to say that most are still on some R&D drawing board, the ones closest to realization likely awaiting a corporate bean counter to calculate the cheapest means of mass production to ensure profitability, the rest languishing in the minds of dreamers. But the fact that we still want these things, we still fantasize about futuristic gizmos from 75 years ago, says something about the power of their ideas, what they mean to us.

Yes, they were cool. Those visionary contraptions played to our imaginations, allowing us to defy gravity and rocket across great distances and travel through the most inhospitable environments in ease and comfort. They let us create things in the wink of an eye, like magic – or like God. We could even, following His lead, make machines in our own image.

Moreover, they looked cool, those devices of future past: streamlined and sleek, built for speed and efficiency but elegant, too, their seductive curves and polished metal surfaces just begging you to run your hands over them, to feel the future.

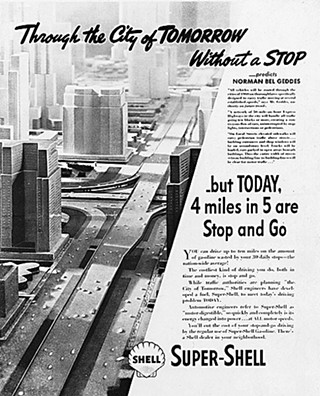

When you look at designs by Norman Bel Geddes – and how convenient, you can in the book Norman Bel Geddes Designs America, being released this very week by Abrams, and in its companion exhibit, "I Have Seen the Future: Norman Bel Geddes Designs America," at the Harry Ransom Center through Jan. 6, 2013 – you'll see those forward-looking inventions of yore in all their shiny appeal, and in their most sophisticated form. See, Bel Geddes wasn't just one more illustrator dashing off bullet-nosed spaceships and lightning-barreled rayguns for the sci-fi pulps. He was a sort of born designer who cut his teeth creating sets and lighting for theatre and opera productions, then moved into industrial design, where he developed the look and style of commercial products from radio cabinets to cocktail shakers, kitchen stoves to typewriters, before turning his hand to more ambitious objects: autos, yachts, airliners, cities. He had a highly developed sense of space and understanding of functionality, so when he smoothed the surface of an object, rounded its edges, it wasn't just for the aesthetics, though that mattered. He was imagining its use, and if it moved, how it moved; he was addressing aerodynamics and improving mobility.

Take a gander at his vision for an airliner. It's really a hotel for the sky, built to carry 450 passengers and 155 crewmen on intercontinental trips, with 302 cabins, 13 pantries, three kitchens, two bars, a veranda cafe, three private and two public dining rooms (one of which converts into a dance floor for 100 couples), an orchestra platform, a promenade deck, a gym, four courts for tennis and six for shuffleboard, a doctor's office, a barber shop, a hair salon, two solariums, and a library spread over nine decks, with a massive engine room and hangars for two emergency airplanes. The scale of it is monumental, which is part of its fascination – nothing like it has ever been built. But Bel Geddes actually designed it from a practical standpoint; it's thought through in exceptional detail, with the flying wing and giant pontoons representing innovative, functional design, as well as looking crazy cool.

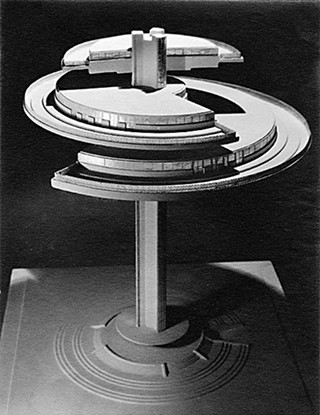

That approach is what makes Futurama, the scale-model City of Tomorrow that Bel Geddes created for the 1939 World's Fair in New York, his masterpiece, and inspired 24 million people to see it. I mean, it was this massive diorama – some 36,000 square feet, with a half-million miniature buildings, two million tiny trees, and 50,000 teeny cars of the future, 10,000 of which raced along on 14-lane highways – and who wouldn't love that? But Bel Geddes was serious about this being a working city that tackled the myriad problems of the modern metropolis – limited land for housing and food production, airport location, stop-and-go traffic – and envisioned solutions: pedestrian walkways above highways, traffic controlled by radio, floating airports, experimental farms. He was pioneering the kind of urban planning that we take for granted today, projecting long-range growth and proposing revolutionary methods for dealing with it. Bel Geddes figured tomorrow ought to be better than today, and he managed to show on an epic scale how it could be.

That's an idea that lost its currency as we slouched toward the future in the waning half of the 20th century. Starting with the Cold War paranoia of the Fifties, the future became ruled by the atom, and between the bomb and the radiation unleashed by it, tomorrow was nothing but the birthplace of freakishly outsized insects or a bombed-out shell of the present – in which case, you might find it lorded over by talking apes or bloodthirsty mutants. By the time we hit the don't-trust-the-establishment Seventies, the future had been bought by corporate interests and was either making meat patties out of people, pushing ultraviolent roller derby, or filling amusement parks with murderous robots. Not surprisingly, at this point, the future also grew increasingly industrial and logo-splattered. About the only time it looked as pleasant as in the era of Futurama was when the government killed you as a 30th birthday present. The future has been pretty much down in the dystopian dumps ever since, either riding down the acid rain-washed mean streets of Blade Runner megalopolises or across the mohawk mutant-festooned Mad Max moonscapes following this or that apocalypse.

Now, those tomorrows have their places, as social critiques of where we are today and cautionary tales of where we'll wind up if we aren't careful, as environments in which our humanity is tested and its virtues – courage, compassion, individuality, imagination, love – can be affirmed, frequently in inspiring ways. What they don't do is inspire us about the future itself. You don't want to think about those tomorrows, much less live in them. They're too dispiriting.

Embedded in the future of Bel Geddes is hope, the hope of a better tomorrow, a world that can improve upon the present through a marriage of ingenuity and engineering. That's a quality that continues to attract us as much as the teardrop shape of his roadsters or rounded edges of that winged hotel. (Speaking of rounded edges, think the ones on that iPhone sprang full-blown from the brow of Steve Jobs? Try a testament to the enduring influence of Bel Geddes' design.)

It's tough to talk about the future and how we perceive it without mentioning Bel Geddes, as will be evident this week as the Ransom Center hosts the 2012 edition of its biennial Flair Symposium. Its title is "Visions of the Future," and a host of prominent scholars, architects, industrial designers, science fiction writers, historians, and futurists will be weighing in on how the future gets imagined, designed, marketed, and driven. Don't expect them to know when we're getting our flying cars, but they probably know why we keep asking for them.

"I Have Seen the Future: Norman Bel Geddes Designs America" is on view through Jan. 6 at the Harry Ransom Center, 21st & Guadalupe, UT campus. For more info, call 471-8944 or visit www.hrc.utexas.edu.

Bruce Sterling delivers the keynote address to the 2012 Flair Symposium, "Visions of the Future," Thursday, Nov. 1, 7:30pm, at Jessen Auditorium in Homer Rainey Hall, UT campus. The public is welcome. For more info, call 471-8944 or visit www.hrc.utexas.edu.