Can't Get There From Here

While suburban rail spends and stumbles, Cap Metro's transit-dependent riders wait at the end of the line

By Lee Nichols, Fri., Jan. 22, 2010

There's something to be said for having a captive customer base. Remember Lily Tomlin playing Ernestine the Telephone Operator in the old Saturday Night Live skit? "We don't care. We don't have to. We're the phone company."

The management of Capital Metro, as well as its board of directors, insists it doesn't share Ernestine's sentiment. But for people who truly depend on public transit for their basic transportation needs, good intentions are hardly enough – and it's a fact that Cap Metro doesn't have to worry much about losing that business to another entity. As a quasi-governmental monopoly company, the agency bears a certain resemblance to AT&T before the feds mandated competition in that industry. Don't like changes that Cap Metro makes? As Ernestine snorted: "Why don't you try using two Dixie cups with a string?"

Of course, Cap Metro operates a transit agency, not a phone company. But if you're poor, handicapped, or otherwise don't have access to an automobile, Ernestine's suggestion is about as good as any.

Sure, those citizens do have avenues to complain. The Capital Metro board is composed of either elected officials or people appointed by elected officials. But lately, the board has voted to raise fares, trim bus routes, change policies regarding services for the handicapped, and halve the yearly funding to upgrade the accessibility of bus stops – all while pouring more than $100 million into a new commuter train, the opening of which is two years behind schedule. Is this any way to treat your most loyal customers?

Obstacle Course

"The less frequently a bus comes or the fewer routes there are, the fewer opportunities you have to be able to travel quickly," says Jennifer McPhail, an organizer with ADAPT of Texas, an activist group dedicated to removing obstacles for individuals with disabilities. McPhail lives near Oltorf and Pleasant Valley, and she's in a wheelchair. "As it is right now, if I want to go see my family that lives in North Austin on the edge of Williamson County, it takes about four hours. That's one way. I got so frustrated, and so did my family, that they said, 'Never mind, we'll come pick you up.'"

Many people on the bus or other Cap Metro vehicles are not there by choice. These folks are called the "transit-dependent." They either can't drive themselves or for whatever reason – choice or poverty – don't have access to a motor vehicle. According to a 2008 customer service survey, 27% of Cap Metro riders do not have access to a vehicle. On some routes, that number is higher than half the riders – topped out by the No. 350 Airport Boulevard bus, at 67%.

I am not one of these riders. If I realize the bus won't get me where I want to go, it's a mere annoyance. If I'm lucky and circumstances allow, I just ride my bike instead. Or I get in my car and bitch about air pollution, traffic, and the price of gasoline and Downtown parking. And I move on with my life.

For McPhail, there's no moving on. It's not an inconvenience – it's a barrier. When Capital Metro cuts back its service, it makes a life already filled with hardship that much harder. Getting to the job or the grocery store becomes more difficult. But transportation is more than that – getting around is crucial to the simple act of being a human being and part of the world. "I can get to Dallas quicker on a Greyhound," she continues. "Is it an acceptable service? No. ... I'm not making any plans to spend the holidays or go see [my nieces and nephews] play soccer."

With the downturn in the economy, Cap Metro insists those cuts are necessary. As has been previously detailed in these pages and elsewhere, Cap Metro has financial problems. Cap Metro's particular crisis is complex: Like many other governmental entities and other transit agencies, a big part of it is a downturn in sales tax revenues. But it's also partly due, by Cap Metro's own admission, to financial mismanagement, including burning up an approximately $200 million reserve since 2002.

That makes the budgetary measures all the more galling to McPhail, one cut in particular: reduced funding to make bus stops more accessible. In May 2008, Cap Metro staff made a shocking presentation to the board: Of the bus system's more than 3,000 stops, two-thirds do not meet updated requirements of the Americans With Disabilities Act for full accessibility. In fiscal year 2009, progress was made – 130 stops were brought up to current ADA requirements – but that pace will likely slow in 2010.

"The board last year committed to us that they would spend $3 million every year for the next five years to address bus stop accessibility problems, but then this year they cut it down to $1.5 million, and some of that is going to be what they call 'amenities,' so it's even less than $1.5 [million]. And if that level of commitment remains, it will take 10 years before we can access all the bus stops in their inventory. That's too long." ("Amenities" can include benches, shelters, trash cans, and other items in addition to accessibility upgrades. Capital Metro says it expects that $1.25 million will be spent directly on accessibility in fiscal year 2010.)

What constitutes an inaccessible stop varies. In almost all cases, the stop lacks a 5-foot-by-8-foot concrete pad; more extreme problems can also include a lack of full connectivity with nearby sidewalk or streets, or perhaps there are no sidewalks with which to connect (which also brings the city of Austin or other municipalities into the discussion; more on that below). I went looking for such stops, and it didn't take long to find them. Within walking distance of my house, on Burnet Road, I found a stop with a pad and bench, but it was separated from the street by a drainage ditch (a pain, I might add, even for fully mobile customers).

A little farther up, I was stunned to find a 2.1-mile stretch of Burnet Road – from Highway 183 north to where the street dead-ends at MoPac – where 12 of 14 stops were simply on grass, in some cases in ditches, or in one case, separated from the sidewalk by a mud pit.

Such conditions are more than an inconvenience for McPhail. She showed me a video of her attempt to get to one such stop, and it's harrowing. She drives her motorized wheelchair into the street, sharing a lane with oncoming, fast-moving traffic, and it's hard not to cringe as each car approaches. "I resent having to risk my life to do everyday things," she says. "It's been a problem throughout Cap Metro's existence, and you can kind of live with it and be patient if people are making a real, sincere effort to provide you access, but this isn't a sincere effort. No one can tell you the exact amount that's being spent on accessibility – so how sincere is that?"

Cap Metro says it can't quantify how many passengers have been injured or killed due to accessibility problems, because it does not track incidents according to that criterion.

MetroAccess

To be fair, McPhail does have another choice in these situations: MetroAccess, the paratransit service, which will deliver her to locations within Cap Metro's service area. But McPhail doesn't want to use it. First, it's not convenient, requiring reservations by 5pm the day prior. And more importantly for McPhail, it violates ADAPT's core mission: integration of the handicapped into society. "ADAPT is supportive of paratransit for those who need it, but it's not really meant as the form of transportation for people with disabilities," McPhail says. "We've always worked for integration of the entire system so that it makes it better for the people who can't ride the bus."

It's a philosophy that she says benefits both the taxpayer and the disabled community. "Paratransit costs about $40 per trip, as opposed to a ride on mainline transit, which is about two bucks a trip, maybe $2.50," McPhail says. That's the total cost of the trip – and on MetroAccess, under the new rates, only $1.20 of that is covered by fares (or less, if the customer uses a multiride pass). The disabled pay no fare on the bus, but the cost differential to Joe and Jane Taxpayer is obvious.

And the benefit to people with disabilities goes beyond dollars and cents, says McPhail.

"People just assume it's okay to force people onto MetroAccess, but it's really not an acceptable answer to the problem," she says. "Not just because it's too expensive but because it segregates people with disabilities from the rest of the community. I've met a lot of my neighbors because we've sat at the bus stop waiting on a bus together. ... It's like a little community gathering. ... You meet a lot of people that way, you forge relationships, and there's a great deal of beauty and purpose in that service. I've seen kids in my neighborhood grow up, and now they have kids of their own."

You Don't Need to Go There

But if you do use MetroAccess, you're feeling the squeeze, too. First off, that $1.20 single-trip fare is a hike from the previous 70 cents. The bigger issue for some MetroAccess users, however, is the new 30-minute pickup window. Riders must call in their requests a day prior, before 5pm. Cap Metro then schedules an actual pickup time, which can be anywhere from one hour before to an hour after your request. Previously, Cap Metro was supposed to show up no later than 15 minutes after promised pickup time, and if it showed up early, the rider was not required to be ready to go. Under the new policy, Cap Metro can arrive up to 15 minutes early or late, and riders are expected to be ready to move anywhere within that time frame. Riders complained in a public meeting last fall that this expanded time frame is just one more drain on their time already disproportionately eaten up by transportation needs.

"That's not as bad if you're at home, but if you're at the mall or anyplace you'd be coming home from. ... If you're at a place that doesn't have seating, you can't just stand there 30 minutes until ... your ride shows up," says Diane Bomar-Aleman, who chairs Cap Metro's Access Advisory Committee and who is visually impaired.

"Here's another thing that's scary: If you can't get to a bus stop, they're [now] saying, 'Okay, we'll give you service to your nearest transit center,'" instead of giving a full point-to-point ride, Bomar-Aleman says. "So picture having a 30-minute window of when they might pick you up, and then all they do is take you over to the transit center, and then you get on the bus.

"The point is, riding the bus isn't just the exercise in and of itself – it's where you're going on the bus that's the difficult part. It's where you're getting off. For me, for instance, there are no pedestrian walkways across parking lots. And so when you get off somewhere that's not Downtown – Lakeline Mall is a good example, because they don't even pull into the mall. Or now they want us to be able to name the places we can't get to on the bus and explain why, and then they will go and investigate and determine if they think we actually could get there on the bus and give us what they call trip-by-trip eligibility. ... If they think you could get there on the bus, you're denied the trip."

Bomar-Aleman also complains that Cap Metro is making it harder to get certified for MetroAccess eligibility. "The application for service hasn't changed, the law hasn't changed, the way people are filling it out hasn't changed, but now they're denying people based on the same answers that have been given for the past 20 years for recertification. People that had the same disability two years ago now are being denied eligibility. This is going on big time right now. There are a lot of appeals being scheduled, but there are a lot of people who just won't schedule appeals [for themselves]. Or they're only approving service for May through August, when they think that it's hot. But in Texas it can be over 100 degrees in April. ... [Capital Metro] is trying to make the service so difficult to use that people just won't use it."

And these changes are on top of a general reduction in service earlier this decade, Bomar-Aleman says. The ADA only requires MetroAccess to provide service to locations within three-quarters of a mile of a bus stop. That makes sense in dense places with lots of transit stations, like Manhattan or Washington, D.C., Bomar-Aleman says, because that effectively covers the whole city. "But they expected [lawmakers] would use common sense," when ADA was enacted, Bomar-Aleman says. "They would use that as a starting point." MetroAccess, then called Special Transit Services, covered a far greater area than just along bus routes, she says. "But around 2002, about the time [recently retired Cap Metro CEO] Fred Gilliam came in, they started restricting. Keep in mind that ADA had already been in effect 11 years, but they used ADA as an excuse to cut back on what they already had, which was better than what ADA required. They can say they're following ADA, but they're misusing the law. The point of the law was to enhance the lives and opportunities of people with disabilities, not [to be used] as an excuse to restrict what already existed.

"They are limiting people with disabilities to do just what the bus does, only that small area that the bus covers," Bomar-Aleman says. Reflecting the position of ADAPT's McPhail, she continues, "So being excluded from anything outside of that ... for instance, they used to go to the Oasis. People have different views on what transit should cover. A lot of people who don't use it think of it as setting trip priorities. 'So what if people don't get to go to the Oasis,' or another place that's just for recreation, that it should only be used for necessities. But to be fully included in society, people have to be fully included in everything. What's the point of living or working or anything if all you can do is get to your medical appointments? You can't have full inclusion without transportation. If you can't get there, you can't be included in it."

The Cincinnati Solution

And then there's the transit-dependent group least likely to show up at Cap Metro board meetings to complain: the poor. Instead, they're more likely to be represented by social service providers and advocates, such as Texas RioGrande Legal Aid.

In 2008, the single-trip bus fare crept up from 50 cents to 75. Now it's up to $1, and other fares have made similar increases. That might not seem like much to most riders, and Cap Metro can make a good case that fares were kept at 50 cents for far too long, lagging well behind its transit-industry peers. Cap Metro currently has one of the lowest fare recovery rates (the percentage of expenses paid by the riders themselves) in the nation. But that's little consolation to the cash-strapped.

"The origin and destination studies Capital Metro has provided show that a majority of low-income and minority riders buy [the] 31-day pass," says D'Ann Johnson of Texas RioGrande Legal Aid. When the single-trip fare went up to 75 cents, the 31-day pass climbed from $10 to $18. Now it's $28.

"We know that increase has a significant impact on people," Johnson says. In fact, it means the transit-dependent poor have seen their travel expenses go up almost $200 per year. "That's for people on fixed incomes. And they aren't choice riders. People at the lower income scale are already making choices between medicine and transportation or food and transportation. If you have less money, those are still choices you're going to have to make."

Cap Metro argues that it has no choice but to raise fares in this time of lowered revenue, especially since it still distributes a number of free or reduced-fare passes to many social service agencies around town.

Management thinks it may have a solution to both the hits the agency takes on the discounts as well as the squeeze put on the poor. The agency wants to form a nonprofit organization to meet the needs of transit-dependent customers, which could seek outside funding. The idea isn't out of the blue – it's been tried in the Cincinnati area as a program called Everybody Rides Metro, and by all accounts we've seen, it's regarded as a success.

But as previously reported in the Chronicle, the reception by some Central Texas charitable organizations has been negative at worst and befuddled at best (see "Nonprofits Not Impressed by Cap Metro Proposal," Nov. 6, 2009). Both board members and management have publicly stated that Cap Metro is a transportation company, not a social service agency. But Johnson and others see it as Cap Metro trying to duck out of its direct obligation to the needy.

"They're a public entity," says Katie Navine, chair of the Basic Needs Coalition of Central Texas. "We're not sure why this isn't part of their mission, to work with their low-income customers. Would another public entity say, 'Oh, I just don't want to deal with this problem'? Could the city say, 'Oh, well, I don't want to deal with this particular population; I think I'll spin this off'? ... Capital Metro is the entity that deals with transportation issues."

Just Ain't Fare

I sat down with Cap Metro top officials for a wide-ranging interview on the issues of the transit-dependent, and their answers almost always came back to the same theme: poverty. Not of their riders, but the agency.

On the reduction in funding for upgrading bus stop accessibility: "Our sales tax is down pretty dramatically," says interim president and CEO Doug Allen, who took over in October when Gilliam stepped down. Cap Metro receives a one-cent sales tax within its service area, which accounts for 72% of its revenues in the 2010 fiscal year budget. "With that sales tax," Allen notes, "we have to operate all our services, and then we also use it to do improvements like the bus stops. When the sales tax went down dramatically, we had to make some tough decisions in all areas. ... It's not a matter of wanting to do it; it's a matter of what kind of resources we have."

Cap Metro also complains that it needs help making the stops accessible. That two-mile stretch of Burnet Road not only lacks concrete pads, it lacks sidewalks to get to the pads – and sidewalks need to come from the city of Austin. "Even if we put a pad there, it's not going to be accessible," says John-Michael Cortez, Cap Metro's community outreach specialist. "We should put a pad in, and I think we have a plan to try to upgrade these stops, but it can't be our responsibility alone to make the whole city accessible."

"We actually do coordinate with [Cap Metro] pretty closely," responded Sara Hartley, spokeswoman for Austin's Public Works Department. "We're trying to build an entire network of ADA-compliant sidewalks throughout the city, but obviously, that's a massive undertaking. Any time we can coordinate with new construction from either Capital Metro in a transit area or put something in knowing something like that is coming, then of course we're going to coordinate that."

Michael Curtis of the city's Neighborhood Connectivity Division says that in fiscal year 2010, his department expects to spend about $4 million on making existing sidewalks ADA-compliant and another $2 million on new sidewalks, which together should result in about seven miles of sidewalks. "And that's just out of my program," Curtis says. "If other departments are engaged in a street reconstruction project, they must put in compliant sidewalks, and that will probably account for another $5 million."

As for complaints that the stops were due to be compliant in 1995, Allen says all Cap Metro stops actually are compliant with the law as it stood at that time, but the two-thirds now considered inaccessible fail to meet the 2006 ADA update. Those stops were grandfathered, although Allen says Cap Metro is still committed to upgrading them. (Actually, that's not quite accurate – in a Jan. 13 presentation to the board, a week after our conversation, John Hodges of Cap Metro's Facilities Design and Construction Department reported that 93 stops are not in compliance with ADA at all, and never were.)

On slimming MetroAccess to the three-quarter-mile service: "It gets back to the resource allocation issue," says Allen. "There's [only] so much money available to the agency, and we have to prioritize the best use of funds. ... To allow us to continue to provide that service, we had to make some adjustments to stay within the ADA requirements. These trips can become very expensive, so we want to do the ADA requirements, but we have to make sure that's what we're doing and not going too drastically beyond that, because when we do, we have to take resources away from some other program, like bus stop accessibility or the ride share program."

That doesn't sit well with critics of the agency such as Bomar-Aleman and McPhail, who feel that at least one program never gets its funds cut: "The thing that bothers me the most is how much they cut the [MetroAccess] service area right after the train referendum passed," says Bomar-Aleman. (Voters approved the building of the new – and still not operational – MetroRail commuter line in 2004.) "They'll say it's a coincidence, but why is it that they can support and encourage people who can drive and already have express buses coming in from Leander and the suburbs and they can put a bunch of money into a train that's just a commuter train, and at the same time cut the services of people who have no other choice?"

"We made a commitment," counters Allen. "We worked with the community, went through a pretty extensive outreach, and went to the voters, and the voters approved the rail project. Once you commit to doing that rail project, you have to complete it. You can't stop it. You have to finish the stations and those things. ... It's just not practical to say, 'Let's stop this a few years until our finances come back around.'" And there were rail cutbacks, says Chief Financial Officer Randy Hume. "If things hadn't been so bad, we'd have purchased more vehicles," he says.

"Going down the road of pitting one against the other is simply not something that I care to get involved in," says Austin Mayor Pro Tem Mike Martinez, one of only three holdovers on a Cap Metro board of directors that was restructured, beginning this year, by state law. "As a policymaker and as a leader and as a board member, I don't have the luxury of saying, 'I'm only going to focus on this.'"

As for the nonprofit to help the poor: "How do we get our passes into the hands of people who really need it but do it in a way that's more fiscally responsible?" asks Allen. "We're still putting a lot of money in it," says Cortez, Cap Metro's point man on the idea. "We're going out and chasing down money from outside the community to put into this fund."

"If we weren't doing this, we'd probably have to contract the program," says Hume. "This is a way to actually expand it to serve more people. ... Cincinnati did this, and they're serving more people than before." (Indeed, sources I spoke with in Cincinnati, both inside and outside Everybody Rides Metro, expressed surprise that Cap Metro's version has encountered opposition.)

Overall, as Allen puts it, Cap Metro is in a bit of a "damned if they do, damned if they don't" position. "A year ago," he says, "there was a lot of justified criticism of the agency of not having their finances in shape and not paying attention to the bottom dollar. Just about everything we've talked about just now has related to getting back to a more fiscally prudent way of doing business, while being compassionate and doing what we can to keep making improvements to bus stops, while making passes available to people with low incomes; so it's a balancing act. ... People don't like to have change made, but it's necessary."

Meanwhile, folks like McPhail will continue rolling their wheelchairs into the Cap Metro board room in East Austin and insisting it's not enough. If history holds, she and other advocates will receive a hearing, but changes will not be radical.

"They're polite, but that doesn't keep you safe," McPhail laments. "I'd rather they do their job and dislike me than to be polite to me and be personable and leave me in oncoming traffic."

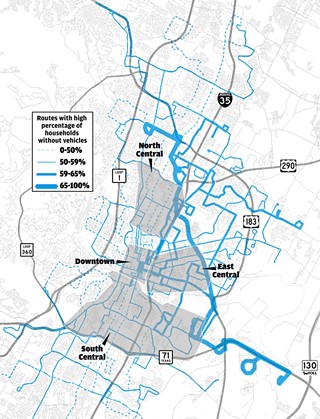

Bus-Dependent Neighborhoods

| Route | Avg. Daily Boardings | Households Without Vehicles |

| 350 – Airport Blvd. | 2,491 | 67% |

| 4 – Montopolis | 1,472 | 63% |

| 15 – Red River | 2,744 | 61% |

| 300 – Govalle | 6,342 | 60% |

| 320 – St. Johns | 1,842 | 60% |

| 37 – Colony Park | 2,694 | 60% |

| 17 – Johnston | 3,514 | 59% |

| 26 – Riverside | 2,248 | 59% |

For bus route changes and fare increases, see "Cap Metro Changes Bus Routes, Hikes Fares."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.