Naked If I Want To

Moby Grape then and now

By Louis Black, Fri., Jan. 8, 2010

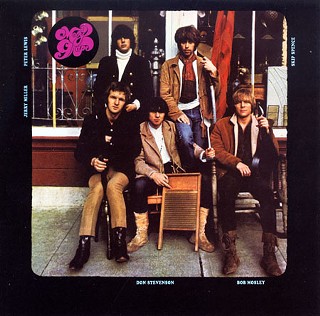

Moby Grape Personnel

Skip Spence: rhythm guitar, vocals

Don Stevenson: drums, vocals

Bob Mosley: bass, vocals

Peter Lewis: rhythm guitar, vocals

Jerry Miller: lead guitar, vocals

'Moby Grape,' the Album

"Hey Grandma" (Miller/Stevenson)

"Mr. Blues" (Mosley)

"Fall on You" (Lewis)

"8:05" (Miller/Stevenson)

"Come in the Morning" (Mosley)

"Omaha" (Spence)

"Naked, If I Want To" (Miller)

"Someday" (Miller/Spence/Stevenson)

"Ain't No Use" (Miller/Stevenson)

"Sitting by the Window" (Lewis)

"Changes" (Miller/Stevenson)

"Lazy Me" (Mosley)

"Indifference" (Spence)

Producer: David Rubinson

Label: Columbia Records

Dates: Recorded March-April 1967; released June 1967

The tale of San Francisco's Moby Grape has become one of the great tragic fables of rock & roll, assuming almost Orson Welles proportions in terms of vast creative loss. Both Welles and Moby Grape came out of the gate at full speed; both produced a first release that reached an aesthetic height rarely achieved. But this accomplishment, rather than an opening benediction to a long career, became an impediment in that it was not only never matched again, but it also became a standard used to judge subsequent work disparagingly.

There were a number of years during which the music coming out of San Francisco was one of the most important forces in American music. Bands began forming by the mid-1960s, but it wasn't until 1967 that the S.F. scene went from rumor to reality to myth.

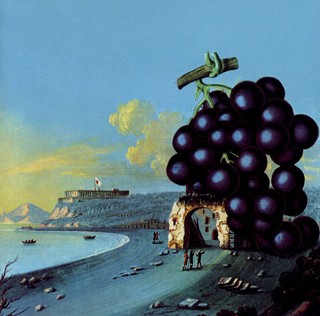

Moby Grape consisted of five singer-songwriter musicians who, after getting together in autumn 1966, spent the next couple of months just practicing. When the band finally began to play clubs, it soon became one of the most popular area acts. In March 1967 the group cut its eponymous debut, Moby Grape, released in June that year to glowing press. The band, however, was hindered by missteps made by its record company.

The label overhyped the band and the album so much that it invited ridicule and derision rather than positive attention. This was just the beginning, as almost anything that could hurt the album did. The band only survived a few years, with members coming and going so that by the last of the four original albums Moby Grape was a trio.

This tragic interpretation still sounds rote and hackneyed. There's this one great album and a number of other terrific records that were recorded and released. There are also the five guys who joined a band and mostly didn't know one another, yet they continued playing together in different combinations for the rest of their lives. The four remaining members still jam on occasion. They're bonded in a very special way. Is there a moral to this story? Maybe there is and maybe not. Regardless, there's this one truly great album.

Moby Grape, one of the very first albums I bought, has stayed in regular rotation on my playlist ever since. Right off I liked it, but when I became a freshman in college a year later, my friend Alan taught me to love it.

Often toward the end of a party, when the earliest light of dawn was beginning to seep through curtained windows, I'd put Moby Grape on the turntable. Turning it up to maximum volume, I'd drop the needle onto "Hey Grandma," the first track. The buzz saw guitar at the beginning of the song would rip through the room, house, and neighborhood. Inevitably, if any guests still remaining were guitarists, they'd ask me to turn it up even louder.

There is no particular reason for this piece at this time. There's no new box set being released or a lot of unreleased material suddenly discovered and available. A while back the four albums officially released by the band were reissued (see "Reissues," Dec. 14, 2007). Almost immediately the band's four-decades-old feud and marathon legal battle with original manager Matthew Katz took Moby Grape and Wow/Grape Jam out of print. There are several excellent compilations.

Any serious conversation regarding American popular music of the last half-century has to begin with a discussion of silence. Not exactly in the same sense that John Cage composed Silence. (NRBQ recorded it, but cut it down to two minutes.) Instead, silence as the backdrop and contest. If anything, as much as American life, media and communication technology have changed the nature of silence. It's not what it was 50 years ago.

Listen My Friends

Moby Grape was released during that astonishing time for rock music between the early 1960s and early 1970s. This was when rock mutated from basic rock & roll into something far more complex and ambitious. Much of this change came about because the many different music genres being listened to were incorporated into rock. It wasn't just genre mixing. It was disregard for any kind of classification with defined boundaries.

This massive cross-fertilization was dependent on and caused by the extensive musical knowledge of the musicians as well as the expertise of so many of them in a variety of genres. How did this come about? Music by Robert Johnson, Dock Boggs, Memphis Minnie, Jimmie Rodgers, Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Bessie Smith, and Bob Willis among so many others was available on recordings. Except they weren't easy to find in the 1950s, when most of this generation of rockers came of age. In many cases there were only a limited number of records pressed and distributed.

It was a time of AM Top 40 radio featuring limited playlists with only a few FM free-form radio stations in the nation. Since only a few musicians, at best, had access to significant libraries of music, most of them just played the records they could find over and over.

The nature of silence and access to music has completely changed how music is consumed. Just a few decades back, listening to music required an effort, as the ways to hear it were by listening to the radio, attending live performances, and playing records. What the radio played and bands' touring schedules were both out of the listeners' control. The only way to hear the music one wanted when one wanted was by playing records.

When Moby Grape was released, albums were very much the standard. Music was criticized, categorized, purchased, collected, cataloged, and chronologically divided by albums. This was before there were 8-tracks in cars or Walkmans, much less the Internet, downloading, iPods, music festivals, extensive rock music media, and rock on TV (except for a few variety shows); forget dedicated channels or a constant soundtrack presence on commercials and shows.

Accessing music is totally different now, most of it regularly available without much in the way of restrictions. Concurrently, most forms of communication – computers, phones – also serve as portals for music. The technological advances of the last decades have changed the very natures of media and interpersonal communication. Now music is mostly listened to as free-floating songs downloaded online, with albums no longer of much value or consequence.

Changes (Changes)

San Francisco was a key location in the lifestyle revolution and generational changes that took place during the 1960s. The Bay Area, long home to alternative lifestyles, was an incubator for the imaginations, thinking, and philosophies of people more interested in looking forward than backward. Music, one of the most important sources of these communities' senses of identity, was also the best way of conveying these new ideas to the outside world. The bands, their stories, records, and music were of an importance that is hard to explain or understand now. Even the names of the groups conveyed mystery – Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grateful Dead, and, of course, Moby Grape.

By the mid-1960s, "San Francisco" had become a term signifying an "other" way of life from what was considered normal America. The city's lifestyles and ideologies were seen as being in opposition (and reaction) to what the "United States" had come to mean – a monolithic nation with a strongly established interlocking set of ideological, economic, social, political, and cultural ideals. The San Francisco lifestyle, centered on expanding consciousness and alternative ways of living, abandoned accepted structures and established traditions.

It was an exotic world with an endless variety of unique looks (long hair, tie-dye, face-painting, psychedelic posters), smells (patchouli oil, incense, marijuana), tastes (brown rice, whole-grain, wok-cooked, no sugar), and lodgings (tepees, Buckminister Fuller domes). A world of different beliefs (American Indian and Eastern religious beliefs) and health supplements (drugs, meditation, and alternative medicinal ideas). Not even distantly linked to suburban American values, its sensibility was pure outlaw, with conformity and personal gain rejected in favor of personal growth and the general good.

More than a specific rock style or overall sound, the "San Francisco Sound" had more to do with the sensibilities and lifestyles of the bands and communities than it did with a shared sound (experience "The San Francisco Sound," Dec. 7, 2007).

The year 1967 kicked off with the Human Be-In: Pow-Wow: A Gathering of the Tribes, Jan. 14, 1967, at the Polo Grounds in Golden Gate Park. Twenty thousand people came together to enjoy a free concert featuring most of the best-known S.F. bands, including the Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother & the Holding Company, the Sir Douglas Quintet, and Country Joe & the Fish. There were guest speakers as well, including Timothy Leary famously urging the audience to turn on, tune in, and drop out for the first time. Allen Ginsberg chanted as Owsley Stanley handed out hits of acid and Dick Gregory and Jerry Rubin preached politics. The crowd, filled with hippies, freaks, and flower children, also counted both the diggers and Hells Angels, each there to help in their own way.

The first major, highly regarded S.F. acts to break into national consciousness were Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead. Interestingly this was not via their music, which had yet to be heard, but rather through national news stories

Jefferson Airplane was part of the scene almost from the beginning. In early 1965, Marty Balin decided to start a band. Soon after he was at a club when a "weird looking guy" carrying two instrument cases entered. Balin gave up his spot on the bill to the newcomer. "He started to play," recalls Balin, "and then just stopped. He said 'I can't do this.'" As Paul Kantner walked off stage, Balin approached him to ask if he wanted to help start a band.

Bass player Bob Harvey and drummer Jerry Peloquin soon joined, as did singer Signe Toly Anderson. One afternoon Balin was sitting around in Kantner's apartment thinking that in order to really rock the band needed a great guitar player. Just then Jorma Kaukonen, having finished giving a guitar lesson upstairs, wandered by and was recruited by Balin.

Soon the Airplane began to play clubs, quickly attracting a large following. When drummer Peloquin left the band, Balin went looking for a replacement. Across the room at a coffeehouse he saw Skip Spence. Liking not only the way he looked but his vibe, Balin asked him to join the band. Spence was a guitarist, not a drummer, though he soon became one. Signed to RCA, this was the lineup of the band that recorded debut LP Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released in August 1966.

Spence not only played drums but contributed two songs to the album. Toward the end of the recording sessions, however, he disappeared, so Spencer Dryden was brought on to replace him as drummer. Jack Casady, an old friend of Kaukonen's, was hired to play bass after the band fired Harvey. When singer Anderson was asked to leave the band, Grace Slick was lured away from her band the Great Society to replace her. This rounded out the lineup of the Airplane that soon would carry it to fame and fortune. Slick proved crucial to that success not only because of her extraordinary voice, but because she brought along with her two songs, her own "White Rabbit" and her former brother-in-law Darby Slick's "Somebody to Love."

Released February 1967, Surrealistic Pillow, the band's second album, proved a phenomenal success, peaking at No. 3 on the Top 100 list while producing two Top 10 hit singles, "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love." This success resulted in national media attention on both the band and the scene exploding exponentially. Soon the other S.F. bands went from just being heard about to finally having their music actually heard.

If the Human Be-In was the scene's kickoff, the Monterey Pop Festival, held June 16-18, 1967, was its coming-of-age. Again, most of the main S.F. groups played, including the Airplane, the Dead, Quicksilver, the Steve Miller Band, Country Joe & the Fish, Moby Grape, and Big Brother. The festival, according to Geoffrey Stokes in Rock of Ages, worked for "the mostly unrecorded San Francisco bands ... who proved they could hold the stage as equals with the festival's certified stars."

Big Brother & the Holding Company, featuring Janis Joplin, blew everyone away, resulting in Albert Grossman becoming the band's manager and CBS Records President Clive Davis signing them. The Grateful Dead was signed to Warner Bros. in 1966, and Quicksilver Messenger Service landed a lucrative record deal from the festival, while the Steve Miller Band was signed to Capitol for an unprecedented $50,000 advance.

Following Monterey, the last half of 1967 saw a flurry of releases by San Francisco bands. Concurrent with the festival, Moby Grape was launched. Big Brother released its first album on Mainstream Records in November 1967. It wasn't until the following year when Columbia released the single "Piece of My Heart" in August and the album Cheap Thrills in September that the band hit the charts. When that happened, it hit big as the album went to No. 1.

Country Joe & the Fish's first album, Electric Music for the Mind and Body, was released in April 1967, with the eponymous Grateful Dead having come out a month earlier. Although the Dead had already begun attracting large audiences to its live performances, for a long time the band was more famous than successful. It wasn't until Workingman's Dead in June 1970, soon followed by American Beauty in November, that the band began to sell albums. Quicksilver Messenger Service didn't come out with an album until May 1968, at which time singer and songwriter Dino Valenti was in jail.

Lifestyle has always been a critical part of the cultural packaging of film, music, and art. Interestingly, new culture usually spreads from its source city outward at its own pace. Frequently when it achieves widespread impact and attracts media attention, it has changed significantly in the place it originated. The last half of 1967 saw the music of many San Francisco bands being available and listened to across the country. In the city, however, the Summer of Love in all its meanings was declared over in October with a mock funeral for the death of the hippie held in the Haight.

What's This Song You're Bringing?

The exact origin of Moby Grape is a bit foggy, with some histories having the band recruited by manager Matthew Katz in a street hip parallel of how the Monkees came together. One version of this has Katz finding Jerry Miller, Don Stevenson, and Bob Mosley first, then Peter Lewis, and finally Spence. Others claim that it was Spence alone who started the band or else it came together more naturally. The version that rings truest is that Katz, who had also managed Jefferson Airplane, knew Spence, so together they decided to build a band around him. This is most likely the accurate version, though it's mentioned only with regret in that it bestows so much credit on Katz, the band's nemesis.

When the band members first came together in the fall of 1966, they didn't really know one another. Way too much has been made of this given that at the beginning of so many bands the musicians come together as relative strangers. What's notable is that they've continued to play together in one configuration or another, up to and including the present.

The strength of the group was that each and every one of them was exceptional in every way. Thus the real story is that these five outstanding singers, brilliant musicians, and excellent songwriters created a cohesive, brilliant body of music in a very short period of time.

Most of them had spent their formative years as musicians working in bar bands. Don Stevenson (drums and vocals) and Jerry Miller (lead guitar and vocals) were from the Pacific Northwest, where both had played the bar band circuit. Miller was in the Bobby Fuller Four, played guitar on "I Fought the Law," and toured the South with the band. Stevenson had also backed jazz and R&B legends such as Big Mama Thornton and Etta James. Stevenson and Miller both ended up in the Frantics, a very popular Northwest bar band that was one of the first to cover "Louie, Louie," though they never recorded it. In an effort to help launch the band nationally they moved to S.F., where they ended up backing topless dancers.

Bob Mosley (bass, vocals) briefly joined the group. Before that he had played with the Misfits in San Diego. Peter Lewis (rhythm guitar, vocals) came aboard next. Lewis, actress Loretta Young's son, had played with surf band the Cornells and Peter & the Wolves. Stevenson, Miller, Mosley, and Lewis: All four were working journeyman musicians who had played any number of gigs in a wide variety of situations.

Besides drumming for Jefferson Airplane, Skip Spence had also briefly been a member of Quicksilver Messenger Service. Spence's impish, soulful spirit and glowing charisma personified Moby Grape.

When the lineup was in place they began to rehearse for eight hours a day at the Ark, a paddleboat turned into a Sausalito, Calif., club. The practice continued through September and October. "In the process [they] went from being an extraordinary collision of strangers to the tightest, most talked about band in San Francisco. The sessions became an off-hour magnet for other Frisco musicians and visiting dignitaries," writes David Fricke.

Even before they began playing public gigs, word on the band brought record companies to hear them. Interest in signing the five was expressed by a number of major labels. After a bidding war the group was signed to Columbia by David Rubinson, who produced not only the exquisite debut album but the next two as well (Wow and Moby Grape '69). When the band began playing out in November 1966, their incendiary performances immediately made them the talk of the town.

One of the last major San Francisco groups to form (late 1966), they were among the first to release an album. Together for some six months, they went down to a studio in Hollywood in March 1967. Three weeks later they finished recording their first album at the cost of $11,000. In the Bay Area there was enormous excitement about this forthcoming album. Unfortunately the record company was about to screw that up.

Columbia overhyped the band in every way imaginable, most notably by releasing five singles simultaneously off Moby Grape that June (10 of the album's 13 songs). The release was celebrated with a gig/party at the Avalon Ballroom, thrown by Columbia. With writers flown in from all over the country, the excess was more repellent than exciting. "Ten thousand purple orchids floated down from the Avalon ceiling, but once on the floor, the slippery petals had people falling ass-over-elbow all night," relates Fricke. There were also 700 bottles of wine that had on them special Moby Grape labels that the record company had printed up, though according to at least one source they had forgotten to have any corkscrews there. The hype was so embarrassing it turned off the critics.

The bad news didn't end there. In the very early hours of the morning after the party, Jerry Miller, Peter Lewis, and Skip Spence were arrested for being with underage girls. Miller was also busted for possession of marijuana. The charges were later dropped, but by then the damage had been done.

The bad mojo continued to mount. Someone at Columbia finally noticed that in the band photo on the cover of the album – already in distribution – Don Stevenson, holding a washboard, was giving the world the finger. Immediately a sticker was put over the offending finger on the copies already printed. The finger was airbrushed out of subsequent pressings.

Finally, the album's release was concurrent with Monterey Pop Festival. Moby Grape also performed at the festival, but whereas the event helped the careers of so many groups, manager Matthew Katz refused to allow the band's inclusion in the subsequent film and live recordings.

Not surprisingly, only one of Moby Grape's five singles broke into the lower rungs of the Top 100. Over time the album has come to be labeled a commercial failure, but it actually did surprisingly well, staying on the charts for six months and peaking at No. 24.

One of the greatest ironies in modern music history is that although the Columbia people were idiots in the execution of the promotion, they were right on target. Five singles off the album could have easily charted. Moby Grape doesn't just live up to the ridiculous hype of its release, it's even better. Not only is it transcendent, it's still so remarkably fresh. Mainly this is because though widely and deeply loved, the album has really not been that influential. Highly regarded it still hasn't passed into legend like Love's Forever Changes or the Zombies' Odessey and Oracle. This may well be because it is not a concept album in any way.

The Byrds albums, for example, from Mr. Tambourine Man through Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde, have been strip-mined for every idea or even hint of one. The last decades of alternative country music are like an index to the Byrds' output, referencing lyrics, music, content, presentation, and narrative. The only way to really relish the brilliance and wonder of those Byrds albums is memory. The Grape's songs have certainly inspired subsequent songwriters but not nearly to the same extremes, so the music comes across as much fresher, not so hackneyed and, ironically, imitative.

Just a Bell Ringing

Moby Grape, released June 1967, is a songwriter's album, as all five members of the band wrote songs and were all truly gifted with no standout songwriter among them. Obviously during those months of rehearsal the five not only came together as a band but had concentrated as a group on recording their best material no matter who had written it to a soulful spit polish.

It was a time when culture was in transition, a period of change that considered the grander questions of living on this planet while effectively changing many of the most mundane aspects of how one lived his or her life. Rather than describing what was going on, Moby Grape's songs were grounded in emotional snapshots of life tightly focused and coming out of the group's daily lives. And there was nothing mundane about their lives.

The Grape neither pushed the musical limits as much as the Grateful Dead nor were as political in their lyrics as Jefferson Airplane. The songs are not calls to arms. They lack polemics, and they neither share morbid visions nor predict the future. The tightest and most polished of all the S.F. groups, it's not that the band didn't push limits or project a unique powerful sound. They just did it their own way. Whether a rock anthem or painfully beautiful ballad it was a Grape song.

Recording the album, the group approached each and every song on its own terms, each loaded with interesting ideas, unique dynamics, and innovative construction. Thirteen songs; each one carefully arranged, performed, recorded, and produced so that though the songs are legendarily tight, they still rock without guile or restraint. Whatever accepted style the songs seem to fit, they're always unique and often surprising.

The album's opener, "Hey Grandma," by Jerry Miller and Don Stevenson, is a rock anthem that begins with stinging electric guitar. It rips from silence to 60 in less than 10 seconds. When the band comes in singing harmony it begins to get unusual. The chain-saw guitar is layered over with lovely harmonies, the ringing sound contrasted with the lyrics: "Hey Grandma, you're so young/Your old man's just a boy/Been a long time this time (pow-pow-pow)/Been a long time this time (pow-pow-pow)."

Almost the "answer" song to the Airplane's "Come Up the Years" although not nearly as specific; it's a work of profound contradictions. The opening lines of the final verse add to the oddness: "Robitussin make me feel so fine/Robitussin and elderberry wine/Hey Grandma."

It's an anthem, or at least it sounds like an anthem, with the music driving forward and the vocals soaring above. But it's not a traditional American rock anthem. Certainly it isn't "Born to Run," "Born to be Wild," or "Roadrunner." It's not "London Calling," "We Will Rock You," or "I Love Rock & Roll."

Whether they're dumb or brilliant, usually American rock anthems at least try for the mythic, yearning for the open road, freedom, romance, and the unknown. They celebrate the outlaw life, sex, revolution, and/or drugs, while frequently being about the singer or the coolness of the band.

Bruce Springsteen is one of the few artists who comes to mind who probably has put out albums with as many anthems as Moby Grape, though the latter lacks his bombast and ambition. Rather than celebrate classic American myths, the Grape's subject matter is more eccentric. Arguably "Changes," "Hey Grandma," "Fall on You," and "Omaha" are all anthems. But the songs are done the Grape's way, not according to any presumed rules or accepted standards.

One of the recurring motifs of these Grape anthems is a grandiose chorus hooked to a much smaller lyric picture. In the musically exuberant but lyrically downbeat "Changes" (Miller and Stevenson), this contrast is further enriched by the seeming philosophical differences between the chorus and the lyrics: "Changes! (Changes!)/Changes! (Changes!)/I'm sure the cure is not there/Anywhere to be found."

The chorus celebrates the mood of the times, but the underlying alienation of the singer is emphasized in the verses: "I try to sympathize with their problems/But my changin' self/Won't keep up with nobody else."

Finally, the song ends with the odd variant on the chorus: "Everybody changes/But the weather's fine/Everybody changes ...."

The song is about changes in the culture, in lives, in relationships, and in general is a carefully constructed contradiction. The tension between the chorus and verses only enriches the song's meaning.

Overall the Grape's lyrics acknowledge these changes going on in the culture and in their lives. There's a strong current of optimism in most of these songs, though failed romances and misplaced dreams are not denied. Still, the melancholy can subvert that optimism as with the moodiness and despair of the singer of "Changes."

Listening to Skip Spence's "Omaha" makes it clear why he was such a legend, a towering talent who simply did things his own way. The verses are classic power song rock & roll, only they're a little spaced out, almost like street hipster haiku except more gleeful: "Now my friends/What's gone down behind/No more rain/From where we came."

And then: "You thought never but/I'm yours forever/Won't leave you ever."

Those simple rock verses become quite literally transcendent set against the big and bold anthemic chorus, a neon electric sign of the times: "Listen my friends/Listen my friends/Listen my friends."

Originally the song was called "Listen My Friends," but Spence for no apparent reason changed the name to "Omaha," even though there's no reference to anything associated with that city. "Omaha" has been covered live in concert by artists such as Bruce Springsteen and on record by groups such as the Golden Palominos on Visions of Excess (1985), with R.E.M.'s Michael Stipe on lead vocal.

The power of the band's eccentric anthems is matched, complemented, and offset by some extraordinarily beautiful love songs, including "Someday," "Sitting by the Window," and especially "8:05." These love songs, as with so much romance portrayed by the Grape, are mostly about separation. Some are outright laments for lost love, but more often they're about losing love, the songs seemingly written at the moment of rupture or shortly thereafter.

In Peter Lewis' "Sitting by the Window," he evokes loss rather than specifically describing it: "I was sitting by the window/Watchin' for the rain/I thought you were beside me/Just like before the rain." He was thinking she was beside him, but she wasn't. She was gone. Again, the melancholy is both amplified and redeemed by a great chorus. Just as subtly, the song talks about how the failure of the relationship comes not just from her but from both of them. The lyric variations in the final chorus show his pained resignation to what has happened: "But just the same/I'm playin' my game/And I guess you're playin' it too."

The achingly lovely "8:05" (Miller and Stevenson) is one of the most covered of the album's songs, by the Grateful Dead, Robert Plant, and Christy McWilson with Dave Alvin, among others. Lacking the undercurrent of driving rock that's either blatant or creeps up as in most Grape songs, it starts gently with guitars and tambourine: "Eight-oh-five/It's useless to try/I guess you're leaving soon."

Beautifully sung throughout, the exquisite harmonies begging a love that's leaving to maybe rethink things prompts electric chills. "Please change your mind/Before my sunshine is gone?" This is followed by a repeated line that becomes the heart of the song. The question it asks is a plea not a demand: "Do you think you could try?/Do you think you could try?/Do you think you could try?"

One singer's voice rises, a counter-rhythm to the harmonies it is riding above and leading to the song's end: "Don't fill my world with rain/You know your tears/Would only bring pain in my heart." You can hear the singers take a breath, then they sing "8:05," followed by a resigned last line: "I guess you're leaving, goodbye ...."

The instruments then drop out, leaving just the voices going high at the very end.

"Come in the Morning" (Mosley) is an anthem and a love song. The song opens with a spoken invitation, "Come on in people, we're going to tell you about good dreams and things to make you happy." Some regard this as the conceptual lead in to the whole album. This is followed by a very Haight-Ashbury hippie lyric: "Come in the morning/When the sun is shining/Bring me a dream/With the sun beams climbing."

Then comes the chorus, "Stay with me now, tomorrow .../Come what may/Girl, come what may." Clearly the singer's inviting a woman to join him, and the invitation is with some urgency. Combining verse and chorus, the song ends by setting the strength of the relationship – "You know I love you" – immediately against life's constantly haunted ambiguity ("Come what may"). It continues: "You know that I need you (Come what may)/I don't want nobody else, baby (Come what may)/I don't need nobody, nobody else, baby (Come what may)/I just want your love (Come what may)."

The genre blending in the songs is unique. When you listen to early Byrds there are elements of folk, hints of bluegrass, country, and country-blues all mixed into rock songs. Early on, even with the mix, the different elements are clearly identifiable. Gram Parsons' first attempts at country rock with the International Submarine Band sound crude and somewhat forced. When he joined the Byrds the resulting Sweetheart of the Rodeo leaned heavily toward country though clearly leavened with rock. Echoes, Gene Clark's first solo album (also released with some differences in songs as Gene Clark With the Gosdin Brothers), more organically incorporates and integrates a number of different styles, while also demonstrating how crucial if underrated were his contributions to the Byrds.

Moby Grape synthesizes so many different forms and genres into music where the original strands are not obvious enough to be easily color-coded. The end result is Moby Grape rock; to label it otherwise as folk-, country-, blues-, psychedelic-, or bluegrass-rock or to try to divine the threads and influences is to demean it.

Many of the songs are truly unique unto themselves.

Take Bob Mosley's "Mr. Blues," for example, an ode to the (Mr.) Blues. Although it's about the blues, it's not a blues but a rock song (with hints of blues and soul). The lyrics start by asking, "Where's that old Mr. Blues? I guess he's got a new home," suggesting the loss of accessible tragedy or the means for dealing with despair. Yet the tune has some sweet soul harmonies. The exception is Mosley's voice as it travels through the song.

"Where's that old Mr. Blues?/I guess he's stepping on through (now)/Pushing down places, all down and abused/Picking on people with nothing to lose."

At times Mosley's gravelly and well-traveled voice on its own seems a purer blues thread wandering through a pop-soul song. Sometimes the voice sounds close to sinking under the weight of sadness the singer carries. Still matched by the music, toward the song's end his voice rises into a kind of soul stuttering, featuring call-and-response phrasing and word emphasis.

"Got to, put down old Mr. Blues (let me tell ya)/Got to put blues down on the table/Got to let the blues go down/Down my throat now."

"Indifference" (Spence) opens with a chorus that immediately takes the song to some other plane. "What a difference a day has made/What a difference a day has made/What a difference and more of the same."

The first verse is more organic to the overall song than the verses in "Omaha."

"What's that song you're singing?/Just a bell ringing in my mind/What's that tune you're bringing?/Just part of what there is to find." The chorus reinforces this, but again, by soaring off itself above the song it ends up expanding it.

The only time Jerry Miller took a solo writing credit was for "Naked, If I Want To," a song that would have been out of place on almost any other album. Which may minimize its truly idiosyncratic status. Surreal, its stream-of-consciousness lyrics are of our world and not of it at all: "Would you let me walk down your street naked if I want to/Can I stop by your work on the Fourth of July/Can I buy an amplifier on time/I ain't got no money/But I will pay you before I die." What other song comes even close to this song's territory? Both Cat Power and Robert Plant have covered it.

In song after song of Moby Grape, there's an overriding sense of the importance of time and of today as separated from yesterday and tomorrow. "What a difference a day has made" ... "Stay with me now, tomorrow/Come what may" ... "Eight-oh-five/It's useless to try/I guess you're leaving soon" ... "I'm yours forever/Won't leave you ever" ... "Here today, gone away."

These songs out of a brave new culture are most often on traditional topics. Although obviously they're tied to San Francisco, they're not restricted by it. As firmly as they are set in the time in which they were written, the contrast between verses and choruses endow them with a timelessness not moored to any particular period.

Been a Long Time This Time Round, This Time Round

Ironically, though the perception that the band failed commercially was way off, any number of other factors did them in. The comedy of tragedies that surrounded the first album's release was a prelude to the band's increasingly bitter, time-consuming, and ugly battle with original manager Matthew Katz. Some of this was about unpaid royalties, but the biggest issue was that Katz owned the band's name. The litigation began in 1969 and continued into the early new millennium.

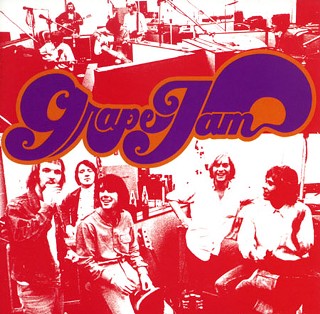

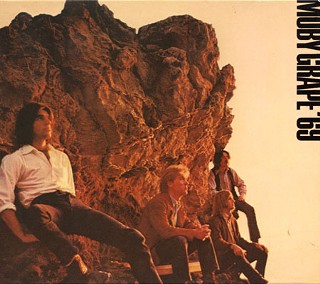

The band's next album, Wow, released April 1968, did even better than Moby Grape, peaking at No. 20. Unfortunately it wasn't as clean and tight as the first album. They also quite foolishly included Grape Jam, a bonus LP featuring special guests such as Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper. This jam LP has always seemed more disconcerting than a welcome bonus. It did, however, inspire Kooper to get together with Stephen Stills and Michael Bloomfield to record Super Session, released August 1968, which was a huge hit, as was its follow-up, The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield & Al Kooper.

The beginning of the end for Moby Grape was not the commercial performance of Wow but recording it. They began working on it at the same Hollywood studio, but all the negative incidents affected the band's morale. At the same time they began partying too much while not working together nearly as well as in the past. Columbia insisted they finish recording in New York. After getting there, Peter Lewis left the band to try and save his marriage. Toward the end of the recording sessions, Skip Spence, who had been teetering on the edge for some time, finally lost it and went looking for Stevenson with an axe. He chopped through the drummer's hotel room door, and not finding him there, he went to the studio. Spence was committed to Bellevue Hospital in the aftermath and remained there for the rest of the album's recording. When released, he took some record company money and his motorcycle to Nashville, where he recorded his lo-fi masterpiece Oar (see "The Memory of Music," Dec. 17, 1999).

In so many ways Spence was the first among equals in Moby Grape. In later years Spence would sometimes sit in with the band, and they would continue to record songs by him on the band's other albums, but he was essentially gone.

Bob Mosley left the band after the third album to join the Marines. Eventually both Mosley and Spence were diagnosed with schizophrenia. Spence died in 1999.

Early on, the Moby Grape record was thought to be an indicator of the band's seemingly unlimited potential. Unfortunately the band never really recovered from the album's disastrous launch or Spence's leaving, so instead it ended up as a document of the band's flaming brilliance.

Buy an Amplifier on Time?

Silence: The end of this story has to be where it began. In silence.

The period that most of the San Francisco musicians grew up in is the same as when I grew up. Silence was prevalent; listening to music was difficult. One did not walk home from school listening to music, and we were not able to find and download almost any music that interested us. Hiding under the covers meant listening to a transistor radio. The music made by the groups talked about in this piece began in silence. Sometimes the only sound was the painful clicking of the clock each time it marked off a minute passed. Sometimes this sound is unheard (and doesn't need to be – it's about the time, not the clock), but sitting in a classroom, praying for the end of the school day, the sound was sharp and brutal.

Silence can be a nurturing and comforting place to think, to dream. It can be graceful and majestic, but it can be boring as well. A half century ago technology was different, communication was simpler, and the dispensation of information more basic. There was sound and noise, and there was silence.

The musicians discussed here grew up, discovered, and learned music in a very different world than the one we live in now. Most important have been the extraordinary changes in media, its relationship to culture and its rapidly changing role in people's lives. In the age of computers and modern communication, the Internet, it's not even outlandish to point out that we used to listen to music (in general interact with culture) very differently than we do now.

Media for most of the last century and before was something that was participated in by people on their terms. They would read a book, go to the movies, listen to the radio, or read a magazine. It required a conscious decision and an effort to access media.

Over the last few decades technological innovations have changed the way we live and communicate. Using a typewriter or writing by hand is so significantly different from using a computer as to be separate, distinct experiences. It used to be that one tried to have most research done before beginning to work on a piece because research was done far from where one wrote. Now with computers connected to the Internet, the nature of research and the retrieval of information has completely changed.

Think about the phone. A telephone once was a landline dial phone unless you were on a rural party line. Dialing took time compared to punching out numbers, though to many even that seems slow. Cell phones now give us fairly constant and flowing access to communication from almost anywhere, but using phones used to be a much more specific effort that always required some planning (this was even before answering machines). The difference in interpersonal communication is almost too complete to contemplate.

But it begins in silence or at least when silence dominated. Silence always generously allows sound, which is far more emphasized when it occurs against that background. This album Moby Grape is by musicians that grew up at the same time as rock, and they created an album that transcends not just the time when it was recorded but all of rock's evolutionary growth stages since then.