Capricorn Jesus

Kris Kristofferson, Stephen Bruton, Momma, and you

By Melinda Hasting Wheatley, Fri., Oct. 16, 2009

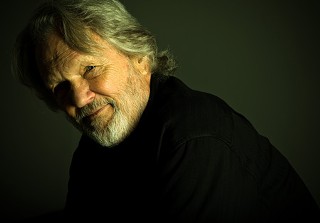

Kris Kristofferson won't let you worship him no matter how hard you try. He'll befriend you to prevent it, smiling widely and asking about you instead. You'll answer because he's shining on you like that.

He tells you he's not a good singer or guitarist. You accidentally nod in agreement because he's so convincing and clear about it. By the time you shake it off to argue his point, he's deflecting glory again. He admits he's a songwriter, but quickly.

You meet him in a local hotel conference room one Sunday afternoon for an interview and watch him chatting with some others, genuinely interested, curious. He's in town to tape an Austin City Limits episode.

His visitors ask where he went to school, and he says simply, "Oxford." His publicist pointedly reminds us that he's a Rhodes scholar. The conversation dies while he fiddles with bottled waters and coffee cups. When he's ready for your interview, he walks over straight-on and leaning slightly sideways shakes your hand stronglike. He sits, smiles, and waits. "You have all the time in the world," his left eye, the braver of the two, says.

He smells faintly of wet tobacco leaves, sweet and maroon. His hair is pale-soft, curled near his ears. He sits in the chair close to you, and the two of you are politely angled outward. He sits whole and open like a good mother would. He's big and broad and strong and looks nothing like 73-year-olds often do, waning. He looks wizened, more feminine and strong. He looks like he's been loved really hard and good for a long time now.

You imagine him in 1972 when you were 6 and your mother was 25. He's smiling on the cover of Jesus Was a Capricorn in dark aviators near long-legged Rita Coolidge in hers. You hold them on your lap on the way home from Kmart, up the hill into the woods where you were living after the divorce.

His beard was thick and dark then. You wanted to sit on his lap on some motorcycle, with Rita nowhere near, so you two could be alone. And you were only 6. But it was a dark-green, East Tennessee summer where women and their daughters can dream about music men and talk openly about it later.

Your mother played that record and received Kristofferson's blessings with soft eyes shut and smiling, tilting right and up, up, to, "Now that I know that I've needed you, so help me Jesus, my soul's in your hands."

You would sit in the yellow kitchen helping her break beans, smiling while she sang. You were her mom, and she was your kid. You were proud of her abandon. Momma was growing up.

You were literal then, so Kristofferson was Jesus, and he was a Capricorn. You held his 33-rpm-sized cardboard image as you listened flat-backed on the hardwood floor in front of massive stereo speakers, seriously reconsidering Jesus, wondering if he could be a hippie, because if so, well.

So anyway, you get this wild hair during the interview and tell Kristofferson an abbreviated form of this story, the part about him being Capricorn Jesus to you way back then. You're being too familiar. He loves it.

He's glad, he tells you, because he thinks some people probably didn't like what he was saying back then. You smile and say, "Not true, not true." You want to say how profoundly he and those outlaws helped your mother blossom. How he was country and strong and looked like your mother's people. How he sang her strongly to sleep after her divorce when she was innocent and lonely with three kids, 2, 4, and 6 years old.

You want to tell him how she trusted him more than the others. Willie Nelson was too dangerous despite her hot attraction. She just knew this. He might want to know that Waylon Jennings was on your momma's shit list for singing his own name first on the live version of "Luckenbach, Texas."

"Waylon and Willie and the boys" was blasphemous, she said. "After all Willie did for him!" she'd cry, gritting her teeth and singing "Willie and Waylon" over it each time, the right way.

So you and your little brothers would sing over it, too: "Willie and Dumb Butt and the boys!" And she'd hush you three, though she'd secretly smile.

But you can't say all this in a hotel conference room where others are waiting to interview him with real questions about the intricacies of songwriting. So you ask about Stephen Bruton, the Austin guitarist who played with him for 30-plus years and died a few months ago. You tell him that Bruton was one of your heroes for slaying the liquor beast. You think Kristofferson will talk of sobriety and the importance of serenity or something, but he launches into smiley, loving tales of his friend when they were both drinking all the time, everywhere.

He tells you of when Bruton was crazy and young and how they went to Russia and got bored one night and decided to play with street people in a gray square tucked into a stairwell to some lucky soul's walk-up. The Russians all around heard the music and began packing into the square in droves, digging the music, digging the Americans' vibe. It was a real impromptu party in a Communist country!

Kristofferson's squinting and gesturing broadly, describing the weird wonderfulness of it all, and you're excited, too.

Then came the military police with their sticks and started hitting the people away, and Kristofferson was standing there, wondering how to make the people safe. When he turned around to his friends, there was Bruton sticking his little mandolin right smack into the faces of the Russian soldiers. He was making some point, which wasn't at all what Kristofferson believed would work. You're watching him remember it slo-mo, shaking his head.

So, after they escaped, Kristofferson called a meeting with the band to discuss the importance of good behavior while in Russia, because after all, they were representing America, for God's sake. Bruton pulled Kristofferson aside after the stern meeting and said, "Sorry, boss," and then revealed that his stateside girlfriend had called to break up with him directly before the riot in the square.

You're thinking, "Well, hell, Bruton – it ain't the free world."

"I had no idea he was goin' through that," Kristofferson goes on, shaking his head again. He's quiet for a moment.

You peer at Capricorn Jesus, turn your body more squarely to him. You like the way he remembers stories about his friends. He notices you doing that and veils his eyes again and tells another Bruton story. You realign to a politer position and pick up your pen.

He was somewhere with Bruton and the band out West, white-water rafting. The water was rough, more aggressive than they were accustomed to, but they had beer and friends, and Kristofferson decided to jump out of the raft and float a ways down the river. He realized too late that the water was too swift and dangerous for swimming. He struggled hard before finally making it to shore. As he recovered his breath, he looked over and saw "Bruton's little head" bobbing rapidly downstream.

Kristofferson widens his eyes at you and says: "Too fast. Way too fast."

As Bruton came upon Kristofferson's shore, there was a look of fear on his face. They grabbed hands but lost grip. Kristofferson instinctively jumped in, and both struggled together, moving fast. He said they had a moment where they knew they were screwed.

Kristofferson pauses and looks you straight on, peering over invisible old-man glasses, and says, "And then a miracle happened," and his face resumes its light as he tells you that a big raft was right around the corner and inside were wet-suited divers who happened to be in the right place and who fished Bruton out of the water and saved him.

"And you, too, right?" you ask. "How'd you get out?"

He shrugs and says that it must've been the adrenaline, and that he got himself to shore. He moves on.

"And our drinkin' buddies were standing there wavin' their beers!" he laughs. "Not a one of 'em thought to jump in and help!"

His and Bruton's hearts were tethered that day. He says that to you in so many words, and with both his eyes. You still wonder how he got out of the water.

He talks about the faith of his childhood, his head honcho status as Episcopal altar boy. He doesn't believe much in organized religion, though. He believes in following the Spirit. He starts talking like that right then, and you connect eyes with him and the room stops still because he reminds you of when you saw him as a kid. He moves into himself and lightens up brighter than ever as he talks about Jesus' good example, how he was a good man to emulate.

You hear a higher frequency in the silence, and the people across the room aren't banging things around anymore. He's talking about his calling, the way he flows rather than fights. It's light in there, and you wonder who Kristofferson really is. He breaks the reverie.

"I just don't know how to talk about it," he says.

You let him off the hook and drop your eyes for the first time in what seems a long time. The interview continues, but you're given a warning sign from the publicist that it's nearly over. So hurriedly, you cover some things.

He talks joyously of his grown children, his grandchildren. And of his beautiful son who wants to join the Army and do crazy shit like his dad did and how ironic and inevitable this is, and you laugh like parents of older kids do when they can.

He tells you he won't skydive again, and you try to convince him the chutes are better than when he was in jump school way back then. He raises his eyebrow and says, "I won't ever know," and you grin wickedly and change the subject.

Obama gives him hope because now there's talk with other leaders before warring with them. There hasn't been anyone like this since the Kennedys, he tells you. "And they killed 'em." You wait for him to go on. He pauses for a beat, then brightens up.

You ask him what young people can do to make music. He tells you that we all have to be the music, be honest, let it get close, and stay real.

"Whatever you do, don't do it for money," he commands sternly. He looks you hard in the eye. "I never expected to make money on this. I got lucky."

The publicist interrupts and says it's time. You look him deep in the eyes one more time, stand, shake his hand, and say goodbye, tingling. He remains, clear and light, ready for the next interview.

Outside, you wonder if you're doing enough to help people.

At home, you sit at the piano, sing-thanking your mother for just about everything. Then you thank Kristofferson and those others for taking her hand and leading her to a husband with a dark beard and guitar who loves her just the way Tennessee men do.

Kristofferson sings "Holy Woman" from your bedroom, and you wonder if you've still got some time to heal.

He walked right out of the water that day, but nobody noticed.

Melinda Hasting Wheatley is a writer, poet, songwriter, and the proud mother of three grown children. She is the acting chief executive officer of American YouthWorks, an Austin-based nonprofit organization that is dedicated to empowering at-risk youth through education and green jobs training.