Chapter 1: Before the Beginning

September 1981-August 1982

Fri., Sept. 7, 2001

This is the story of a group of people who got together to put out a magazine even though, it turned out, they had no idea what they were doing. The first year, especially, was a learning experience. Doing everything wrong was a way to get to doing things right. This is Chapter 1.

The next six years of biweekly production were still a learning curve, but we got ever more surefooted along the way. The mid-Eighties, until we went weekly, were a golden period of Chronicle editorial. This is Chapter 2.

The third chapter details the period between September 1988, when we went weekly, until August 1991, when we moved to our current location. During that period SXSW grew to be a force: The Chronicle was thrown out of the HEB chain, then reinstated, as well as being involved in the political outrage over Barton Creek development.

The Nineties are summed up in Chapter 4, charting a less stressful time, as the paper grows from a dysfunctional family to a real functioning institution.

Finally, Chapter 5 is really the opening chapter of the next period -- who the hell knows what it might bring?

This work is edited. Often writers' submissions have been broken into multiple parts. This story, then, is just part of the story. More is left out than is included, more great writers not asked to contribute than asked. There is no way to overemphasize the magnitude of this disclaimer. A 20-year history of great writers and great writing must suffer when shrunk to fit this hole. As long as this story is, it is woefully incomplete.

Three more-or-less objective buoy markers are anchored to help steer this flood of words. "Austin" designates a section that gives some Austin history and background. "Chronicle History" is about the internal history of the paper. In "Chronicle Content" is the story of how the paper was impacting the community; rarely did the paper adequately convey the often-rabid intensity that accompanied its regular creation.

Publisher Nick Barbaro

If anybody tells you this story and doesn't begin with Nick Barbaro, then, at the very best, they are telling a lie. Nick is the leader, Nick is the moral center. In the earliest days of the Chronicle, Nick believed passionately in several things, among them moving forward by communistic/ democratic consensus, and that he was always right.

The first year started months before publication and was taken up in endless and endlessly long meetings discussing the paper. It took three days to decide on The Austin Chronicle (The Austin Eye, anyone?) and two days to argue over whether or not we were going to accept massage parlor ads a half-decade before we were offered one. If the vote was 5 to 1 against Nick, the discussion would pause for a respectful second and then proceed as though no vote was taken until we all came around to Nick's point of view or reached a new compromise.

This might be a petty story to offer if Nick weren't so often right and the rest of us wrong. Nick Barbaro runs this ship and taught me how to do business. Learning to listen to what Nick was saying was one of the smartest things I ever did. We could empty out this issue and start telling the Nick Barbaro tales and fill it a couple of times over. Remember, every time you read about me calling up a writer or hiring a person, Nick was part of that process. He read every piece; he approved every move. There were writers who never got a call because Nick just didn't like their stuff. There are writers he championed. More than that he had a vision of how this paper should relate to the community and how a business should conduct itself.

We were having a party behind Rollo Banks' China Sea Tattoo Company about a block from our office (Michael Corcoran lived in the back storeroom). We had arranged trade for beer, but, it being a Saturday, we had to pick the kegs up by a certain time. The beer distributor was 15 minutes away. Five minutes before the last possible second we can pick it up, Nick and company pull into the parking lot in a truck. I am furious. Nick is delighted. They had stopped to buy a new basketball, with which he was very happy. We hit every red light. As usual, my anger cup runneth over. Finally, we get to the old Shiner distributorship on Pleasant Valley Road. They've waited; we get the beer. Still, I'm angry; back in the days of no money, these parties, which gushed food and drink gathered on trade, were critical.

When we got back to Rollo's, I started ranting about what a jerk Nick was, how he was late, how he was late because he stopped to buy a ball, how we almost didn't get the beer. Nick was just happy. Rollo laughed at me. "That's why he's the Captain," he offered. "Look, you worried about being late, about not getting the beer. Nick didn't worry. Nick has his ball and got the beer. He's the Captain and," he slapped his ass and added, "It doesn't matter a rat's ass how hysterical you get, Nick is in control of the ship, and all your worrying is worthless." -- Louis Black

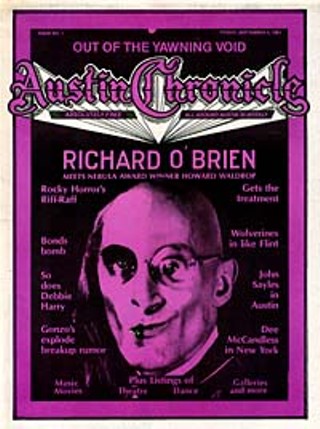

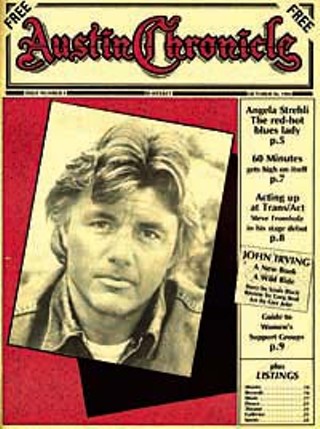

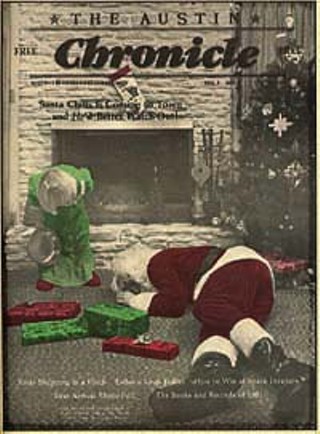

The notorious Vol. 1, No. 1, in which the printer screwed up the color key and Richard O'Brien's face was rendered dark purple

The notorious Vol. 1, No. 1, in which the printer screwed up the color key and Richard O'Brien's face was rendered dark purple

Prehistory The Village Voice

Austin History

The Daily Texan, The Texas Ranger, The Texas Observer, The Austin Sun, The Rag, Free & Easy, Jeff Nightbyrd, Michael Ventura, Dave Moriaty, Sara Clark, Ginger Varney, Big Boy Medlin, Bill Bentley, Jaxon ... we tip our hats to those who taught us.

1981, Pre-September

Chronicle History: Nick Barbaro dropped out of graduate film school at UT, and went to work in a convenience store. Married to Kathleen Maher, he was 30. His background included prep school and UCLA. Joe Dishner had graduated college and become a special education teacher in San Antonio. After a couple of years he quit and, while his wife continued her residency in S.A., moved to Austin and enrolled in film school. After a semester he dropped out, thinking college about film was silly, and decided to talk Nick into starting a paper. Joe and Nick did not, in fact, meet in film school (they didn't overlap), but through Ed Lowry, a legendary film personality who was the leader and teacher of a generation of UT film students that included Barbaro, Louis Black, and Marjorie Baumgarten (with a special nod to high-school-on buddy Michael Barker). Nick and Joe asked Louis Black, a writer for The Daily Texan and CinemaTexas; Sarah Whistler, an editor at The Daily Texan; legendary Daily Texan writer Jeff Whittington; and Lowry, the former head of CinemaTexas and an RTF Ph.D. student, to be on the editorial board.

They started planning the paper. This group would meet for hours and talk about the paper and argue about the paper. They drafted first ad manager Rhett Beard (who while serving a short visit as a guest of the state was listed as travel editor in the old Austin Sun), Texan Art Director Karen Hurley, and non-Texan writer Margaret Moser, borrowed some money from Nick's mom, borrowed more money from her to buy a typesetting machine (about $24,000 -- by the end of the decade they were obsolete). More people joined up, and in the middle of the summer a prototype issue was published. When the monthly city magazine Third Coast debuted, they sped up their schedule and put out the first issue on September 4, 1981. It was a disaster.

There were three cornerstones to the early Chronicle crowd:

CinemaTexas A graduate-student-run film society at UT's RTF Department, where Marge Baumgarten, Nick Barbaro, Louis Black, and Ed Lowry met. CinemaTexas showed movies in conjunction with classes in the Radio-Television-Film Department (where they were all graduate students) four nights a week. Each film was accompanied by a set of program notes, carefully researched and thought through.

Marjorie Baumgarten

I was trying to write my master's thesis for the UT film department, after what seemed like a zillion years in graduate school. It was becoming increasingly evident to me that writing and thinking in terms of chapters just wasn't my thing. I had been writing and editing newspapers since I was in high school, although I had contributed only occasional work to The Daily Texan while in graduate school. The CinemaTexas office had been a hub for the pre-planning of the Chronicle since Nick, Louis, and Ed were also all graduate students at the time, and the CT office was our longtime clubhouse. I was employed in various work-study jobs in the office that involved mimeographing the program notes and managing the box office. We, and others, were there fairly constantly. My late evenings were often spent over at Louis and Ed's, in the house they shared (on Hollywood, curiously enough), watching the 16mm movies we'd take home from the office and project on the living room wall. They'd also ramble on about the long, involved theoretical -- and hypothetical -- arguments that had taken place that night at the Chronicle meetings.

Sarah Whistler

Sarah Whistler

The Daily Texan The student newspaper at the University of Texas where many of the different players in this early history meet up. This includes Jeff Whittington and Sarah Whistler meeting Barbaro, Black, Lowry, and subsequently Joe Dishner, which lead directly to the Chronicle. Other folks who passed through the Texan include but are not limited to Steve Davis, Jay Trachtenberg, Marge Baumgarten, Sylvia Bravo Martindale, Karen Hurley, Cindy Widner, Brent Grulke, Jody Denberg, and Mark McKinnon, among others.

Sylvia Bravo Martindale

One of the earliest meetings for forming the Chronicle took place in The Daily Texan's coffee break room. I remember Joe Dishner so tense he was carrying around a bottle of Rolaids.Jody Denberg

It was 1981 in the gray subterranean kitchen of The Daily Texan newsroom, and myself, Louis Black, Nick Barbaro, Jeff Whittington, et al., were no longer going to be able to write for the paper's entertainment section because we were all leaving school. (Of course, that didn't stop us from using the video display terminals for years after in the pre-PC age.)So Nick and Louis hatched the idea to start our own paper -- one free of the university's bureaucracies, and an idea that preceded the proliferation of weekly rags. I believe the motivation for the Chronicle was present in those early meetings, and it has remained the same: to serve the community and to give ourselves and others a chance to express ourselves in print (and maybe to keep the complimentary records and tickets coming). Obviously, the Chronicle has become a successful business enterprise, but in the early days, if memory serves, the whole thing was floated -- printing, the original Lavaca offices, paying writers, etc. -- from an inheritance received by Nick. This was not mercenary territory. It was the oxymoronic "controlled anarchy." Which led to the Austin Music Awards, SXSW, and Austin's recognition as a world-class city economically and artistically for better or for worse.

Karen Hurley

Some time in the spring of 1981, I was in the back shop at The Daily Texan late one weekend, and Nick Barbaro was there. He said he was starting a paper, asked if I would help, and I said, "Sure." I hadn't known him for very long -- I think he'd been out of the country for a while. That following summer, I pasted up most of the prototype issue on my bed.Nick used to lead the meetings, and he wanted to hear everyone's opinion. Some of them got very long and theoretical. I remember Nick wanted a politics section from the very beginning. They wanted to fashion the look and feel of the paper after the Dallas Observer.

Steve Davis

I started writing film reviews for The Daily Texan in 1978, but when I became entertainment editor, my relationship with Nick and Louis changed. Louis juggled writing weekly music and film columns along with film reviews and thought pieces during my editorial stint while Nick wrote film reviews and an occasional feature article for me. Our passing acquaintances developed into something both professional and personal.Upon hearing in mid-1981 that these two were forming a new publication, The Austin Chronicle, my reaction was immediate: Nick and Louis as authority figures? I had a difficult time imagining it. While I admired their work as writers, my experience as their editor didn't instill much confidence in their ability to succeed in this new enterprise. When Louis wasn't cajoling me into giving him a particular assignment, he was often submitting his copy just under the wire. Organization and deadlines were not his strong points. On a whim, Nick once deleted every file in the newspaper computer's entertainment bank -- I saw my quasi-professional life as a journalist flash before my eyes during the two or three hours it took to retrieve them from the mainframe's bowels. And I never once saw the man wear a pair of long pants, not even in the dead of winter. These two, as editor and publisher of a biweekly publication? I had my doubts.

Mark McKinnon

In the late Seventies at The Daily Texan, Nick Barbaro and Louis Black were slackers before slackers were cool. Hip, smart, and indifferent to style or what anyone thought about them or much of anything else, Barbaro and Black trolled the back rooms of the Texan entertainment offices like a couple of jacked-up, jazzed-out Jack Kerouacs dropped from a time machine into Austin, Texas. They often wore black, not to be cool but to blend in with the night. And one thing was constant and sure. Louis and Nick loved and knew film, music, and culture.

None of us really belonged there at the time. We were cultural anomalies. During a time of rampant conservatism and fraternity hazing, we were bomb-throwing anarchists from places like Boulder and New Jersey! Our whacked-out columns rarely made us popular on campus. (After one particular editorial rant against the fraternity system, I was hung in effigy.) Twentysomething years later, I'm struck by the fact that (A) we're not all in jail; (B) we're parents; and (C) now we're the establishment. I'm also struck by how faithfully Nick and Louis have clung to their cultural roots and their love of film, music, and culture. They wanted to make that love live. And they made it live through the creation of The Austin Chronicle. The blood of Black and Barbaro courses through every issue, and Austin's a better place for it, even if the Chronicle did destroy The Daily Texan. But, hey, that's capitalism, baby! The New Maturity.

Raul"s Austin's Punk/New Wave club on the Drag -- now the location of the Texas Showdown -- where everyone hung out. More than any place the incubator of the community that birthed the Chronicle.

Margaret Moser

My life in newspapers began at The Austin Sun in 1976. Jeff Nightbyrd was the Sun's editor and had been editor of the militant NY publication Rat. He was also national vice-president of the Students for a Democratic Society in the Sixties, and I found a strange affinity with that radical underground. The Sun was important to me because I understood the power of the alternative press from a young age.The Sun set by 1979, and I futzed around an entertainment rag called Rumours, where I met Jim Shahin, but it went under not long after. In the late spring of 1981, Jeff Whittington told me Nick Barbaro and Louis Black were starting a paper and he wanted me to write for it. Me, the outsider, a high school dropout who wasn't a student at UT. I said yes. I remember sitting in my tiny West Campus apartment banging out a column for the prototype issue on a barely functioning manual typewriter left by an errant boyfriend.

In the Seventies I lived for music and going out to nightclubs. Live music was why I moved to Austin, and I lost boyfriends, husbands, and jobs over my pursuit of it. I came for the country music and found the blues, but when punk hit Austin by way of the Sex Pistols in San Antonio in January 1978, I knew it was my last shot at being part of a groundswell movement. I instinctively understood punk's importance musically as well as sociologically, though at the time I simply felt it was my right to party. Nick Barbaro loomed large in my mind as a martyr for his part in the Huns bust in September 1978. Louis Black I had officially met when I was sitting on Jeff's lap in the editorial offices of The Daily Texan. Louis walked by and saw us making out. When we came up for air, Jeff said, "That was Louis Black. Now this will be all over the office." "Really?" I was surprised. Louis seemed like such a serious guy, not a gossiper at all.

I didn't know that Louis considered me valuable because of my notorious-woman mystique. That was probably because I had slept with John Cale a bunch of times and was shameless about it. My girlfriends were a gaggle of groupies known as the Texas Blondes, and we ruled the backstages of Austin and pretty much anywhere else we wanted like rock & roll courtesans. Raul's (and later Club Foot) was our home base, and I was fascinated by it not only for the music but as a magnet for creative energy. Every night was an adventure. It was the CBGB/Max's of Austin and spun off talents that are still doing incredible things.

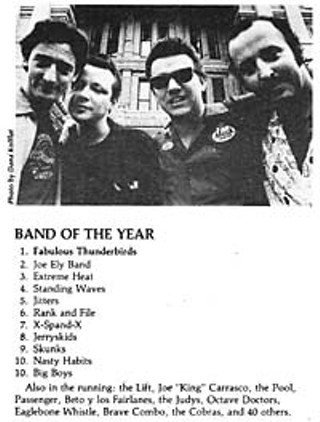

The do-it-yourself ethic really meant something. We all took it to heart. Jeff Whittington, Louis Black, and Nick Barbaro were not just writers for the Texan but participants of the scene. Steve Chaney was a scenester, Roland Swenson managed Standing Waves, Jesse Sublett had the Skunks, and Lois Richwine was his girlfriend, E.A. Srere was writing for Sluggo! and playing in the Chickadiesels ... that's a snapshot of 1979. It's not hard to imagine the seeds of an alternative publication being sown under the giant rats painted on the wall to the sound of "Sister Ray."

September 1981

The "Chronicle" Begins Publishing Austin: A still-sleepy town on the verge of its first great wave of change. Major issues include getting out of the South Texas Nuclear Project, the city manager (always enormously controversial, until the advent of current Manager Jesus Garza), and no-growth vs. pro-growth, as the environmental argument was then cast. Both the Armadillo World Headquarters, Austin famed concert hall where country met rock, and Raul's, the home of Austin's punk/New Wave scene, had closed. Stevie Ray Vaughan was still playing small clubs. The music scene was in transition. The city's population: 345, 496 -- maybe a half million for the greater Austin area.

Chronicle History: The first Chronicle office was a set out of a particularly bleak black comedy. It was a huge loft space above Jack Brown dry cleaners and the old Half Price Books store on Lavaca at 16th, across from Dan's Liquor. Now it is a parking garage. Half the space was occupied by Sheauxnough Studios, a collective of infamous post-Armadillo artists who had found the space and worked out of it. Some lived there. In the Chronicle half, they put a desk and built a three-room house to encase the typesetter, camera, and flats. The house was air-conditioned to keep the typesetter at the right temperature. The rest of the enormous loft wasn't -- the owner's wife thought window air conditioners unattractive. This was the office for the first 18 months and site of many, many a psychodrama.

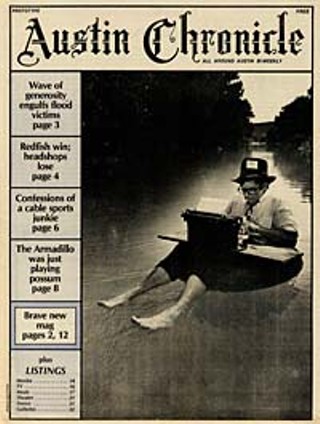

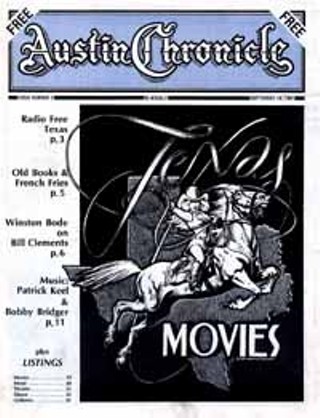

Chronicle Content: Despite the disastrous first cover, the paper was at least readable from the start, if somewhat confused about its identity. The chaos of creation of the first year is not readily evident in the pages produced. The paper began as a 24-page biweekly; during the first summer, we did issues as small as 16 pages. Still, the bylines of such stalwarts as Louis Black, Margaret Moser, Nick Barbaro, Robert Faires. Steve Davis, Jay Trachtenberg, Jody Denberg, Ed Ward, Chris Walters, Kathleen Barbaro (now Maher), Michael Ventura, and Marjorie Baumgarten appeared in the first year, and those are just the ones who still regularly or occasionally write for the Chronicle. The first year is an act of self-creation by the Chronicle staff.

Karen Hurley

Our first printer was in Taylor; then we moved to Marble Falls. At first, the printers didn't take us seriously. Joe Dishner would visit them dressed in a suit and tie to make us look legitimate. Once we chose the printer, I designed the dummy sheets (something used to lay out the paper) and figured out the paper and column sizes. Nick and I met with the representative from Compugraphic and we chose the EditWriter -- it was something like $25,000. I got to pick the fonts -- Palatino (more commonly known as Palladium today) for main body text, Oracle (now called Optima) for listings, and Clarendon and Helios for headlines and ads.Trivia note No. 1: The original page design had four columns each with a width of 14 picas and a 1-pica gutter in between. (A pica is 1/6 of an inch.)

1981: The First Issue

Chronicle History: The first issue was published the first week of September. It was a disaster. The cover was supposed to be half the face of Richard O'Brien from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (a huge cult hit in Austin from early on) and half from his new movie Shock Treatment. At the last minute, cover designer Micael Priest decided to put a dab of purple in each eye to give it a hint of madness. The printer misread the instructions and the cover was a purple mess with a face sneaking through and two dabs of white in the eyes. Fortunately, the distribution system was barely set up, and distribution was, at best, spotty.Karen Hurley

It was a nightmare. Micael Priest, who designed the cover, had been very specific about the overlays, but the printer screwed it all up. Plus there wasn't much of a distribution system. The cover wasn't as attractive as we had wanted it to be, which caused a negative reaction in some of the stores where the paper was being distributed.Joe Dishner

Do I tell the story of how Chuck Dunaway at KLBJ called me up at 6am the morning we published our first issue and threatened to kill me because it was so unbelievably bad?

Recoup 1981

Chronicle History: The many long hours spent planning the first issue grew even longer in the two weeks that followed the disastrous first issue. By the second issue, footing was regained. They were learning how to put out a paper.Kathleen Maher

Now that I'm safely away from the little white clapboard box that was the typesetting and production room of The Austin Chronicle in its early days, I can tell you that yes indeed, there is Zen in typing.In the early days, as you are no doubt desperately tired of hearing, the Chronicle existed in a warehouse on Lavaca Street, occupied now by a concrete parking garage when last I checked. Given the desperate finances, the loft was an un-airconditionable space, but the big blue Compugraphic typesetter we bought secondhand was a demanding mistress and would not function if she was too hot. She would not function under many conditions, as a matter of fact, but at least we could control the AC. To do that, we built a plywood box that was just big enough to hold the chugging, old-fashioned typesetter and the slanted linoleum boards that held the layout pages. The little room was a boon for those of us in the production department, Karen Hurley who steadfastly laid out the thing and me who typeset a lot of it because the rest of the staff was either sweating it out or freezing in that warehouse. As I remember it, I was typesetting through all hours of the days and nights that blurred together without weekend in those days of biweekly.

And, if you typeset for hours and hours with the right kind of music and maybe even a little good copy, you can get yourself in the zone, where you can keep on typing forever. You are one with the machine. You are in another, better place. You cannot make a mistake. Or at least it feels that way.

Music was the key. In those early days, there were intense battles over the stereo. We shared communal space and we shared communal music. And those of us in our cool, air-conditioned little white box functioned in a realm completely estranged from that of our colleagues out in the main part of the loft, who were sleeping on tatty couches, or the hammock, working at the desks scattered haphazardly around the loft, or in cubicles next door at Sheauxnough. At three o'clock in the morning, life may have wound down a bit. More often, life didn't wind down at all, and instead people drifted in and out from the clubs, deep conversations were going on, but in the white box we were in another place with music setting the pace. Joe Ely's "I keep my fingernails long so they click when I play the piano" was obviously appropriate. The Clash's "Rock the Casbah" has the perfect beat, and there is almost no repetitive exercise that reggae does not make more holy. If it wasn't Peter Tosh it was Bob Marley, and it was good. And that's when the outside world was bad.

Sometimes it was just perfect when the sun was just coming up over the Austin skyline (though we didn't know it in our white box). Karen's blond head would be bobbing just over the light table. The fingers would be all warmed up, well-oiled and flying and then someone from outside would change the music. I will never, ever forget the effect of Margaret Moser putting on Wagner's "Ride of the Valkyrie" because she'd heard just a little bit more reggae than she wanted to tolerate on a long night. I thought my heart would stop.

Tempers sometimes flared. The one deemed most sleep-deprived and psychotic usually won. I believe a general ban on Wagner in the dead of night was issued since the wailing Valkyries had kind of an unsettling effect on a lot of people. And always the work settled back into its pace, the rhythm eventually would be restored. The paper always somehow got out.

Karen Hurley

The first Chronicle logo was designed by Micael Priest. Shortly after the Chronicle started, we changed to a new logo by Hal Weiner.Trivia note No. 2: The Hal Weiner version stuck until September 21, 1984, when it was replaced with a new logo designed by Paul Sabal.

Margaret Moser

I was incredibly proud to be part of the new Austin Chronicle. Working at the Sun got me hooked on the newspaper biz, but at the Chronicle I had a very strong sense of being in the right place at the right time as well as being the link between the two papers. My boyfriend then was writer and High Times editor Michael Reynolds, but he was more my boyfriend than I was his girlfriend. He encouraged my writing and showed me how to think like a writer as well as drink like one, though he was more of a pro at both. Sometime around then I was trying to move, with his help. He left to go buy cigarettes and returned two days later with Jimmie Dale Gilmore. Both were drunk. But it was just another one of Those Nights of flaming, frantic youth.Roland Swenson

I knew Louis, Kathleen Maher, Margaret Moser, Jeff Whittington, and a few others from Raul's and The Daily Texan. I attended the Chronicle launch party at Rhett Beard's telephone answering service office in 1981. The first time I went down to the Chronicle loft on 16th Street, I was there to pester Margaret for coverage on one of the bands I was working for. I remember Marge Baumgarten answering phones in the lobby. The space was filthy and incredibly hot. I thought, "These people are crazy. How can they stand being here?"Kevin Connor

I got to town in August of '81, about a month before the first issue of the Chronicle hit the streets. Having come from Boston, a city with two major alternative papers at that time, I was happy to see its debut. Trying to catch on somewhere/somehow in Austin media, I responded to an ad for volunteers at the first Chron office above the dry cleaners. It was close to my basement apartment on 12th, which was good because I didn't have wheels, not even a bike at that point. All I really remember is that Margaret Moser was nice and friendly and Ed Ward was not. Ed seemed to lurk around and leer suspiciously at us volunteers, as if to say, "What are you doing here?!!" And since there wasn't much to do, I wondered the same thing. So I stopped showing up, and I didn't really have much contact with the Chron, except as a reader, until '87, when Roland Swenson and Cayce Cage came to the Z-102 offices. (We slid some pretty great Austin songs in between the classic rock in those days.) Roland said, "We're doing this thing called South by Southwest and we'd like you to be our radio sponsor."Winston Bode

I discovered The Austin Chronicle about the time Nick Barbaro started publishing it. I had a two-part story on brash Republican upstart Gov. Bill Clements in the second and third issues of the Chronicle. The pieces ran in the fall of 1981 -- and they got me into trouble. Not so much with Clements at first -- he got to me later -- but with a rival of Nick's who wanted the story badly.I was rolling pretty good with the state's first sustained political radio-TV panel, Capital Eye, when I met Nick. Something about the sincere, lanky, California-loose Barbaro made me think he was going somewhere. We talked about my doing a story on Clements, Texas' first Republican governor since Reconstruction, and Nick said something like, "Yeah, I'll take it." The story ran long, and Nick said that was okay. He'd just run it in two parts. That really impressed me about Nick because it is true a writer hates to see his stuff cut. But in working on Capital Eye with Bo Byers and Jon Ford and Ernie Stromberger among others, I'd gotten a pretty good bead on the Capitol scene. It helped that by the time I wrote the piece, Ford had joined Clements' staff as his press secretary. Jon manfully supplied me details as I asked for them -- and deep down, I don't think Clements would have wanted it any other way.

The lead on the second installment read: "To a large degree, what Texans see in Bill Clements is what they get -- a self-assured, hard-nosed Texas tycoon whom President Nixon called to Washington in 1972 to manage the Pentagon." The text went on: "Clements is clearly not all things to all people. Part of his strength and part of his vulnerability, lie in what you think about Richard Nixon and what The Dallas Morning News says Clements called the 'Penty-gon.'"

I truly forget how the manuscript of the story made it from the cluttered office of the fledgling Chronicle to the office of rival Third Coast magazine. I recall a vigorous set-to with a Third Coast editor who told me he could cut my Clements story by a third and make it read just as well. When I refused him, he wrote me a letter in which he told me in effect I was a prima donna who couldn't bear to see a single precious word edited!

In 1982, fast-talking Attorney General Mark White toppled Clements for the Democrats. Clements, amazingly, turned around and recaptured the office in 1986. I attended a Clements press conference about this time. I was out of the fray for the moment, having had indigestion and five bypasses one night. I went up and said hello to Clements after the press conference. I added, "I just had a heart attack, Governor." Clements, whom some compared to a banty rooster, cocked his head back and said, "I didn't know you had a heart, Winston!"

Jody Denberg

I contributed a feature on Bobby Bridger to the second issue of the Chron -- missing out on the ill-fated purple debut paper -- and wrote regularly during its first years while doing the odd radio show. From 1984 through 1989, most of my writing appeared in Texas Monthly. No slight to the Chronicle, but TexMo paid very well, and I did not have aspirations at that time of giving my life to the Chron -- a prerequisite to being a regular part of its weekly production.Michael Reynolds

My first recollection is the dog-killing heat in the puppy Chronicle "office." The heat was such that -- apart from shorts and T-shirts -- office attire was endured in a sacrificial act of commitment to the fashion goddesses. A post-punk-attired Margaret Moser manning the communications front from a cluttered street-rescued civil servant's desk. A dry-walled cubicle to her left that housed a cramped lay-out operation -- nothing digital working in there but Mexican-speed-induced human fingers.At that point the Chronicle was a struggling but very game pack of nuevo journalistas, artists, and undecided kids fed by the crazy-smart visions of Nick and Louis. Mizz Margaret had added me to her stable of socially incapacitated writers and musicians that she sheltered beneath her soft wings. Black was then given to backyard film screenings augmented by mini-acoustic concerts that, if my shotgunned memory serves, included Lucinda Williams and Jimmie Dale Gilmore and the Judys -- but I could be wrong. I could easily have that mixed up with some other magical night. Such nights back then seemed as routine as bottles of Shiner Bock.

I came into the Chronicle scene after having done my time in the "alternative" press a decade earlier out in California and had a certain fondness for this next generation and almost no impact on its phenomenal success. Cowpunk boots, lots of bandannas, leather, early, tattoos, and piercing street rat punk-greasy Fourth Ward Houston pimp styles, charro costumes, and lots of hats ... all this would fuse in the night before dawn way down south on Congress.

Other than a jittery account of a tour bus adventure to New Orleans with the Fabulous Thunderbirds, I can't recall contributing much more to the Chronicle troops than very dangerous rides in my green Impala with the police interceptor engine. There was a lot of late-night moving between apartments back then, which made the big Chevy a prize. Mizz Margaret was the major client. Three times we transported her vast collections of newsprint, vinyl LPs, photos, souvenirs, costumes, bangles, letters ... we are talking here about archival moves on the UT Huntington Library scale. These paramilitary-like operations -- to and from various perches and lairs scattered around the city -- were woven into endless nights on a club circuit that was becoming a legend in America. There's no need for me to go into all that, to name the names, cite the moments: Read the back issues and weep for it all, either in aching recognition or regret.

A handful survived those Rocket '88 days when stars were bursting and the oil patch was busting ... some are dead, some are broke, some came back. The Chron kept it up, making fools of those who didn't believe -- the heat couldn't kill it, the yuppies couldn't kill it, it couldn't even kill itself -- it's the Big Dog now because it was so full of heart when it hit the porch as a scrappy little pup.

Ed Ward

By the time the Chronicle started, I'd been at the American-Statesman for less than two years, but I was already feeling hemmed in. I knew the Chronicle folks: They were the faces I saw repeatedly at Raul's and Club Foot and Duke's, the people who showed up at the parties I attended. When they said they were starting an alternative paper, I knew I had to help them out. Trouble was, of course, that I couldn't get caught. The Statesman folks had never really trusted me, since I had never worked at a daily before, and they didn't really approve of all the stuff I covered, particularly that punk rock stuff. So I used pseudonyms. Petaluma Pete was one -- he covered the food beat.Olive Graham

When I started writing for the Chronicle in 1981, I was an ex-officio member of the Laguna Gloria Board of Directors through my membership in the Austin Chapter of Links. This board position was part of their burgeoning effort to reach out to a wider community than they usually served. When I suggested an "Images of Blacks in Film" series, staff went to work and submitted a successful proposal to the Texas Commission for the Humanities. I selected the films and wrote the program notes. The films were screened at the University of Texas at Austin and Huston-Tillotson College. The subject of the image of blacks in film had been my principal academic interest in the doctoral program in the Radio-TV-Film Department at the University of Texas at Austin. Also, I had written program notes for CinemaTexas.Twenty years ago, specialty film series sponsored by museums or art groups were the source of productions from minority or independent filmmakers. Certain film and video catalogs made decades of black-cast films available at reasonable rates, and I had begun renting these for my own academic research. I wanted to share some of those early treasures with a wider audience. A silent film such as Scar of Shame is one of the most impressive examples of silent film storytelling available. One of the series even provided the opportunity to see Spike Lee's thesis film from NYU, Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads.

Now cable channels provide some limited access to the dramas of Oscar Micheaux, comedies from Spencer Williams, and early work from ultimate stars like Lena Horne and Paul Robeson before their Hollywood fame. None of these so-called "race" films had a wide audience and were usually shown in segregated theaters to black audiences. Times have changed, and the mainstream public has embraced comedy productions from Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence and thought-provoking work from Spike Lee. Whether or not the racial images and impressions have actually changed is still an issue, but there is no question that the problem of access to the mainstream viewing public has been solved.

R.U. Steinberg

My first involvement with The Austin Chronicle led to me being chewed out by Robert Fripp of King Crimson. It was 1981, and I was a wet-behind-the-ears, 19-year-old entertainment writer at The Daily Texan. I knew a lot of the folks who started the Chronicle, and I, too, wanted to get involved. So when Jody Denberg asked me to take photos of King Crimson for a Chronicle story he was writing, I jumped at the opportunity. I even offered to drive us to the interview in my 1978 Cutlass.

We headed off to the band's sound check at the Austin Opera House. Jody went off to a room somewhere to interview Adrian Belew while I stayed in the concert hall to take photos when the band came on stage. Bill Bruford warmed up on the drums for what seemed like a long time. I snapped a few photos of him but didn't think much of it. Then the rest of the band came out -- everyone except Belew -- and finally, I could start.

About six shots into the roll, Robert Fripp exclaimed, "What is this? We're not ready for photos!" He didn't even address me, but seemed to blurt it out into the vast emptiness of the auditorium, as if God Almighty would answer him with a lightning bolt. Two rather large burly gentlemen came from opposite sides of the hall to escort me to the parking lot.

And so there I sat in my Cutlass, waiting for Jody. I never got credit for the shot of Bruford that ran. It was a really bad shot.

Early 1982 Austin: The boom was beginning. Fueled by easy savings-and-loan money, the value of real estate shot up.

Chronicle History: Ad sales were dismal and far less than expected. Everyone was making a heroic effort to keep it going. The editorial board kept begging Nick to go to his mother for more money. It peaked during a December 1981 meeting at Dishner's house when everyone responded when asked what they would have for the next issue. "Well if we are going to stay in business I'm planning on running this but if it is the last issue then I'll do this ..." Nick stormed out. He got a little more money from his mother. In early 1982, she made it clear she was no longer a source for funding. Thus began several years of cash-flow hell. At the time we felt abandoned by Nick's mom but realized later how hopeless our situation looked.

Margaret Moser

The name "Miss America" was whispered in those stifling early days. It seemed Nick's mother, Marilyn Buferd, had been Miss America. This added cachet to the bizarre mystique of working in a sweat pit. Marilyn came to the 16th Street office only once that I can remember, as her physical infirmities made the stairs difficult. She was a tall, elegant, and very striking woman, and her sensibilities probably kept her out of our office after that.Nick came into the office one day and poked around. An hour or so later he mentioned his mother was with him. "Where?" I asked. "Downstairs in my car," he replied. This was mid-summer. I ran across Sheauxnough Studios and looked out the window. Sure enough, there she was, the former Miss America. She had finally gotten out of Nick's beat-up old Datsun named Esmerelda and was leaning against it, waiting for her son. In that heat!!!!

S. Emerson Moffat

How Miss America helped start the Chronicle:Marilyn Buferd was a UCLA co-ed and Miss California when she took the Miss America title in September 1946. Entering on a lark, she didn't even choose her talent piece until she was on the plane to Atlantic City, then flubbed her lines onstage. She nailed the swimsuit contest, though, beating out a field that included Cloris Leachman, that year's Miss Illinois. And Marilyn was gorgeous. Life magazine shows a glowing brunette -- leggy, sleek, quick-eyed. Bess Myerson crowned her. She was 21. Marilyn used her scholarship money to take language classes at Berlitz, then scooted off to Europe as soon as her reign was up. She modeled prototype bikinis in France, then moved on to Italy, where she appeared in such films as Roberto Rossellini's The Machine to Kill Bad People. She also began a public relationship with director Rossellini, known as the "hors d'oeuvre affair" (pre-Ingrid Bergman, that is). The tabloids loved it. His wife Anna Magnani was not amused.

In 1951, Marilyn married Franco Barbaro, a former submarine commander under Mussolini, itself a minor scandal with war memories still raw. Later that year, back in Santa Monica, she gave birth to future Chronicle publisher Nick Barbaro. Divorced soon after, Marilyn returned to California, where she raised her son while appearing in occasional films and TV shows. Later married to plumbing magnate Milton Stevens, Marilyn supplied critical financial backing to the Chronicle in the early years. True, she thought her son and his friends were largely nuts. True, she viewed the investment primarily as a tax write-off. True, she persisted in giving Brooks Brothers shirts to her annoyed child well past the point of reason. But the fact remains, you wouldn't be reading this paper today if not for her.

March 1982

Chronicle History: Having run out of investment money, the Chronicle entered cash-flow hell, where it stayed for the rest of the decade. Six months into it, the staff had figured out how to function, but was beginning to be overwhelmed by the unendingness of it all, issue followed issue with dead certainty even in the midst of chaos. People who started the paper began to leave and new people came on board.Sidney Brammer

When I first joined the Chron, I wrote theatre criticism from a distance and didn't have much to do with the actual location. One reason was because I had already done hard time in the location as underappreciated steady girl to one of the Sheauxnough Studio artists. As such, I was already all too familiar with the decades of caked lint and filth that hung from the rafters and wafted down upon the pitted concrete floor and our woolly heads. I had spent a sweltering summer or two gasping for a breath of air in that former sweat shop and fur vault -- what would possibly induce me to return?! A green-eyed blonde with good shoes and a wicked tongue lured me back into that second floor oven. Her name was Sarah Whistler, she avowed as how she had to move to L.A. And I was going to have to take her place as Arts editor. I had never been an editor before, and an old saying went through my head -- something that my friend Jo Carol is fond of repeating -- "It's a horse, better saddle it up."Within a few weeks of becoming the new Arts editor, I had found myself another pal -- a charming valley girl (as in Rio Grande) named Carolyn Phillips, who was one of the first advertising staff members at the paper. She and I decided that life was much too miserable for all of us there, and since Nick didn't seem to have the wherewithal to move the whole operation to an air-conditioned office building downtown, we decided to paint the floor green. I can't remember anymore why that seemed to be such a good idea at the time, something about green being a cooling color or some such hippie girl shit. Anyway, we took it upon ourselves to paint the floor, and while we were at it we hung some ferns and a big hammock that had been wadded up in Nick's inbox for some time. In those days, the Chron only came out every other week, so we had a vacated weekend to complete the task.

First we vacuumed, then "etched" the concrete with muriatic acid -- wearing sunglasses, facemasks, long pants, and Playtex Living Gloves so that we didn't mar our svelte, young bodies. Then we painted it with a sticky concrete floor paint that took hours and hours to dry. We unveiled the newly redecorated office to the staff the next Wednesday; they were kind of stunned, I think. I don't know if it cooled things off, but the hammock went over well.

Margaret Moser

I was really mad at Sidney Brammer and was stewing about her at Club Foot during a Gang of Four show. She was there, and I had a few drinks and a lot of speed. I was walking with Art Director Karen Hurley on one of the upper levels when Sidney came toward me. She gave both of us a friendly greeting, but I hauled off and slapped her, saying, "That's for me." I slapped her again. "That's for the Chronicle."Sidney was stunned and speechless. I marched off smugly and have felt terrible about it ever since. If I could undo something from that time, that would be it. I'm truly sorry, Sid.

Ramsey Wiggins

In 1976, I had left my position as advertising director at the increasingly dysfunctional Armadillo World Headquarters, confused and exhausted. When Jeff Nightbyrd of The Austin Sun asked me if I would use some of my record company contacts to sell advertising for that paper, I took him up on it, more or less as a lark. Bad mistake.For the next five years, advertising sales seemed the only job I could get, other than as a clerk in a head shop. I also developed a deep and abiding relationship with the salesman's friend, cocaine. At 40, while doing a bad job at the L.A. Weekly, I had an epiphany. Don't sell advertising anymore! I quit my job, hung around Los Angeles for awhile, then packed everything into my red Subaru and headed back to Austin. Where I was offered another job in advertising, this time at the fledgling Chronicle. They thought I was a pro. What the hell.

It was like being on the set of an Andy Hardy movie, only with sex. It was blazing hot in the summer and freezing in the winter, and totally funky.

Egos clashed, tempers flared, love affairs were begun and terminated, and personality disorders came into full flower. Everybody was taken beyond his or her physical, emotional, and intellectual limits, through fear to terror and into redemption, and most of us rose up the next day to try again. Somehow out of all this a 24-page newspaper emerged every other week, one that people actually read. What a rush. I had a great time, but my salesmen weren't selling, and I was blotto every night by dark.

Eventually, Nick came to his senses and had the accountant fire me. It was a wise move: I was moving into a rapidly accelerating slide down the razor blade of addiction that would last another eight years. But still ...

Margaret Moser

The first thing I had done after seeing the prototype issue was to tell Nick he needed someone to run the front desk, answer phones, take ad calls messages, etc., and naturally suggested myself. It was my first experience with the Nick-will-say-yes-to-anything-Louis-will-say-no-to-everything syndrome, and Nick hired me. Despite the conditions, it was a fabulous job. I set up the original Chronicle mailing list and contacted record companies, book publishers, and any movie studios that would take my calls. I loved being the first person you saw and working 30 feet from all the cute and talented artists at Sheauxnough Studios I could flirt with daily.My presence set the general office hours and I came in around 10am. More like 10:30am, sometimes 11am and, more times than I care to admit, later. It was true my "night job" required me to stay out late, but the office requirements were still secondary to the all-night partying, and Nick and Louis finally did what they should have long before and fired me off the front desk job.

It was devastating. I knew fully well I had been terrible at the job, but I cried bitterly about it. They replaced me with Marge Baumgarten from CinemaTexas. I couldn't really resent her for it especially since she immediately did a better job. And I didn't have to wake up early any more. That was 1982 on 16th Street, and in 1991 on 40th Street we shared an office together, beginning one of the best, coolest relationships I have with any of my girlfriends. What do I regret most about working at home? I miss my office mate.

June 11, 1982

Chronicle History: The cover of this issue isn't exceptional: a look at the old network comedies being shown on Christian Broadcasting Network. Yet it is a crucial issue. Carolyn Phillips' name appeared for the first time in the staff box. She was a sales rep.

Carolyn sold ads. She was the first ad rep who not only really got the paper but also understood what it could do for her clients. She insisted they be in the paper because she believed it was good for them, and she was right. She sold like crazy. But she was full service. She advised businesses and helped design ads. In those days, when the wall between editorial and advertising was vague, she wrote for the Chronicle, covering music and culture. Phillips came up with the Austin Songwriter series, among other music series, and The Austin Chronicle Musicians Register, and the "Best of Austin" winners banners seen everywhere around town. She even served a spell as sales manager, but realized she much preferred working with the small businesses in which she so passionately believed. Two decades later, many are still around, some have grown to become large businesses, and most still advertise with the Chronicle; their ad rep: Carolyn Phillips.

The stories contained herein are, for the most part, of the most public personalities of the Chronicle: the writers, the artists, the characters. But the reality always was that this is a real-time business. Every week (two weeks, then) an issue had to be produced, bills had to be paid. As Nick Barbaro once noted, "we don't produce a paper for a living, we sell advertising." The reality is that the work of advertising, classified, production, house, and distribution staff allow this paper to exist.

As important as the debut of a writer or editor is the emergence of a sales rep. Susan Grady started around the same time and also proved to be a good rep. Phillips and Grady were soon followed by Deborah Valencia and Lois Richwine and later Jerald Corder, who served a half decade as advertising director, hiring Annette Shelton along the way. All of them are still with the paper.

In the first years, producing a paper proved to be easier than selling it. There was an atmosphere of despair. They had gone through two sales managers in about eight months without much luck. When Phillips and Grady, followed by Valencia and Richwine, first went out and sold the paper, they brought hope.

This date is here to celebrate the large unsung staff that made and make this paper happen. The day Carolyn Phillips officially joined The Austin Chronicle. ![]()