All Access

Austin's B-Side Entertainment rethinks how to get a movie to the masses

By Mike Kanin, Fri., Feb. 20, 2009

On Jan. 25, The New York Times ran what was a fairly glum take on the 2009 edition of the Sundance Film Festival. There, mixed in among various Chicken Little-isms, reporter Michael Cieply quotes filmmaker Joe Swanberg, director of Alexander the Last, as saying, "I've come to realize that my festival run is my theatrical run." Cieply's use of Swanberg is meant as a reinforcement – a personification of the woe afflicting his picture of things as they stand. And it's in that spirit, as he turns from Swanberg to continue his article, that Cieply offers the following bridge: "If Sundance was a lesson in diminished expectations for most ...." He doesn't stop to wonder if his implication – that every filmmaker whose work misses a theatrical run is some poor sap suffering from "diminished expectations" – is a fair one.

For the record, Chris Hyams' Sundance was not as gloomy as the one portrayed in the pages of The New York Times. On the Friday the festival opened, Hyams' Austin-based B-Side Entertainment – which was already busy providing a select group of filmmakers with some pretty savvy public-relations help and the cinema-nerd world at large with a free, easy-to-use Web-based interface for film festivals – announced that it would receive $4.25 million to help fund a full-on play for a slice of the feature-film distribution world. For Hyams and B-Side (www.bside.com), this fresh infusion of cash did indeed mark a sort of arrival. But, more to the point, it also signaled a further business-world endorsement of Hyams' approach to distributing films – one that would seem to totally recast Swanberg's comments.

If you go by years, Hyams is an industry veteran. "At the age of 5, I decided that I was going to write and direct movies," he says. His father – longtime writer and director Peter Hyams (Running Scared) – was in the business; despite the wizened paternal advice the younger Hyams says he got, he couldn't help but throw his precocious hat into the ring. An impressively large collection of homemade Super-8 films followed, as did various on-the-lot second assistant jobs: gigs which earned Hyams both actual onscreen credit and proximity to the creative side of the world he hoped to soon join.

Then he took an internship with Elliot Kastner's production company. There, as he observed the realities of what it takes to get a film made, he became more cynical about his chosen field. "Going to work for this production company ... [I saw] the business end," he says. That experience, he adds, was crushing. "I was young and impressionable. ... [I] thought that it was really about art and creativity. And [I] realized, oh no, it's just about money." So, having spent roughly 15 years thinking of nothing other than film and how to make it and now suffering from total disillusionment, Hyams quit the business. He was 20.

It wouldn't last.

His return to the industry started with the issue of too many options. In the middle of the Internet boom, Trilogy – a software company that Hyams, who now had a master's degree in computer science, had gone to work for –had contracted with Ford to build the research and shopping portion of its website. Among its interactive features, Hyams and his team included a design-your-own page – a place where, as he says, "you could configure your silver Eddie Bauer with a moonroof and a third-row seat." This may have provided would-be Explorer buyers with hours of at-home fun, but it also presented Ford with an age-old industry dilemma: In offering its customers a ridiculous variety of options, an auto manufacturer also hamstrings itself at the sales lot. "There are literally hundreds of different choices that you can make. Some of those have 10 or 15 different choices [themselves]," Hyams explains. "If you multiply out all of those, you could build 150 billion unique, different types of F-350s. The largest lot in Texas has about 200."

Except that now, thanks to the fact that the Ford site prompted its visitors for their ZIP codes before they could begin to outfit their future cars, the company was sitting on a mountain of regional data that could be turned into a tool to predict future sales. "We cut half a billion [in] costs out of their supply chain in the first year from doing that," Hyams says.

It would occur to him that this model for determining consumer interest could be applied to more than just the selling of cars.

In the meantime, Hyams' brother John had picked up the family mantle. "[He] had been sitting around with me all those times that we were watching my Dad work. ... Because he was younger, and I said I wanted to be the director, it was sort of mine," Hyams says. "But as soon as I stepped aside, he kind of came out. He's a brilliant writer; he's an incredibly talented director. And he's been making independent films for the last 15 years."

Hyams would eventually be able to watch some of his brother's work on HBO. But, in keeping with the experiences of most independent filmmakers, many of John's efforts got their first runs at festivals. And it was there, while playing the role of spectator in a place where he'd always thought he'd be a participant, that Hyams had something of a revelation. "What immediately struck me ... was how many amazing films there were out there," he says. "[And] 99 out of 100 were never seen again outside of the festival circuit."

There was something else: His brother's two festival-screened films were each documentaries, one called The Smashing Machine, which followed the exploits of mixed-martial artist Mark Kerr, and one called Rank, which explored the world of professional bull riding. As Hyams points out, their respective theoretical audiences extended well outside the walls of the arthouse theatre.

"Ultimate Fighting at one point in time was the fastest growing sport in the U.S.," he says. "Eight out of 10 of the top pay-per-view events of all time were Ultimate Fighting events. And professional bull riding? One hundred twenty million people a year watch PBR events either in person or on OLN or on NBC."

Despite all of this, no one made any effort to market either film to a broader audience –at least until a Wal-Mart buyer made the logical connection, picked up Rank, and put it on a shelf, says Hyams, "by the Skoal and the Wranglers." There, it would become the bestselling IFC-released title, thanks to little more than smart placement – the act of being able to predict which audience was right for this particular film – and word of mouth.

From his experience with the Ford website, Hyams knew that with a bit of technology, the former was totally doable – and without a distributor having to rely on guesswork and luck. And he'd seen that there were films – tons of them – that might actually do relatively well and without the insane marketing costs often incurred by big studio productions – provided the right people heard about them.

With that in mind, he started B-Side in 2005.

The company – which had swelled by the end of the first year to include Hyams, current lead developer Meetesh Karia, and three others – began by offering film festivals a free Web home that would, according to B-Side promotional materials, allow audiences to "rate the films they've seen, share information on those films with friends, and get recommendations from other film goers."

"It was awesome," says Austin Film Festival founder Barbara Morgan, whose festival served as the B-Side guinea pig. "It was everything that Chris said [it would be] and more."

That success was followed by others, and four years later, B-Side's stable of festivals numbers well more than 200. Along the way, the Web-based software that B-Side offers has more or less revolutionized festivalgoers' experiences. Still, to be the finest dot-com purveyor of film festival support did not represent the alpha and omega of Hyams' ambitions. "The initial idea," he says, "was [that we'd] be able to distribute films."

How many people visit a film's page on a festival's site? How many of those people actually bought tickets or added it to their personal schedules (another B-Side Web feature)? Which of those people came back to talk about and/or rate the film? What did they say about that film? And which other films did those people like and dislike? Hyams could figure out all of this just by looking at his stats. And, in terms of B-Side's next step, that data was far more valuable than any money the company might have earned – if it had been charging its festival partners.

But before we continue, there's something that you should know: According to Hyams, "every single movie loses money at the box office." It's a matter of the traditional marketing model, where the cost of making the 35mm prints and advertising the film's existence will eventually outweigh any box-office profit that a film might make. "The real revenue," he adds, "comes from DVDs, from television, from foreign sales, and, in some cases – when you have the Spider-Mans, the Supermans, and the Harry Potters – from merchandising and other things like that." Trouble was that, because a film's theatrical release was linked directly to the success of those ancillary sales, no one had yet figured out a viable way around spending the cash. It's why the industry has been such an either/or place; it's why Ceiply assumed that Swanberg's statement was a lament. And it's why B-Side might just remake at least a portion of the industry.

About a year after it was first founded, B-Side took its first crack at testing its distribution theories with Before the Music Dies, director Andrew Shapter's examination of the music industry. B-Side's original, theatreless release plan called for the filmmakers to get in the proverbial van and do a 10-city, rock-style tour. But when a key sponsor dropped out at the last minute – taking $150,000 of the budget with it – Hyams & Co. were forced to rethink their plans. "And so we basically, very quickly, made the shift ... to anyone who wants to show the film and host a screening is welcome to do so," Hyams says. "You can do it for free; you can charge whatever you want at the door; you can keep all of the proceeds."

This was the key to the B-Side innovation: Once a film was ready for distribution, all an interested company needed to do – if it was the right film – was to creatively hand it off to the masses. And – if it was the right film – word would spread, DVDs would sell, and release costs would plummet. "Essentially, the idea is [still] what a traditional distributor does," Hyams says. "We partner with other organizations, individuals, people who have the ability to host their own event and who are – for whatever reason – passionate about the subject matter of the film and let them do that work for us in exchange for letting them keep all of the proceeds."

"[That's] a radical idea."

And it's produced radical results. The next production that B-Side took a crack at, a ... chronic version of Super Size Me called Super High Me, would, on an $8,000 budget, celebrate the widest "on-paper," as Hyams calls it, single-day opening in the history of the industry. And later, when it came time to check on the residual effect of the film – in this case by using Netflix statistics as a barometer – Super High Me was, in the first days of its release, added to more queues than Four Months, Three Weeks and Two Days (115,000-110,000, if you're keeping score), a traditionally marketed arthouse film which had won, among other honors, Cannes' Palme d'Or.

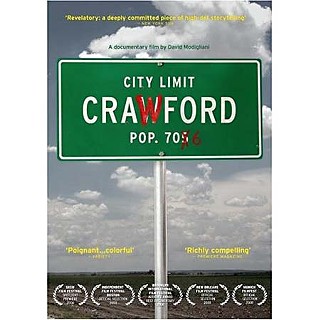

More recently, Hyams and B-Side took on distribution duties for Crawford, David Modigliani's Dubya-as-seen-by-the-small-Texas-town-he-invaded take on the latest Bush presidency. For its premiere, they turned – in what Modigliani terms a first-of-its-kind move – to online entertainment provider Hulu.

"The numbers were staggering," says Modigliani. "More people saw Crawford in its first three days on Hulu than saw the opening weekends of An Inconvenient Truth or March of the Penguins or all but 15 or 16 documentaries ever."

As a follow-up, Modigliani and B-Side cooked up a model-appropriate "Host Your Own Farewell to W." campaign which has, to date, used the end of the Bush administration to earn Crawford screenings in 39 states.

Modigliani is now a true believer in B-Side's distribution model. "We were able to create a buzz and awareness around the film that would normally require a huge amount of print and advertising costs for very, very little," he says.

Throughout our conversation, Hyams is careful to point out that his model will not work for just any film. "It only works for [something] that when people see it, they really fall in love with it," he says. "It has to be a film that has got some kind of hook – something that ... a group of people ... would care about."

"It turns out there's a huge number of those."

And, in spite of the gloomy presumptions of one New York Times reporter, at least one group of investors would seem to agree. Which is to say that, by all appearances, another Hyams has made his mark on the film industry.