Chac-Mool

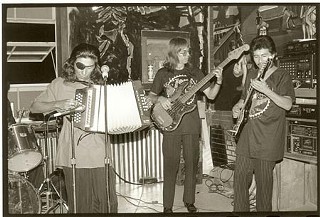

Sitting with accordion king Steve Jordan

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Aug. 8, 2008

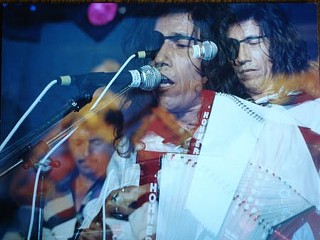

In the legend, Esteban "Steve" Jordan is always playing for his life. His spidery, turquoise-and-silver-laden fingers squeeze the custom Hohner diatonic accordion, in and out, in and out, the snakelike bellows expanding and contracting. The wild mane of hair, once black as jet, is now shot with gray, framing his thin face dominated by the ever-present patch over one eye. Pirates of the Caribbean missed the boat not casting him in a cantina scene.

The patch gets all the attention, but it's the other eye Steve Jordan keeps casting about him. "A couple of spots on my liver" is all he acknowledges of the cancer that's taken down the 69-year-old San Antonian in recent months. Chemotherapy has thinned out his mane, but he's not one to comment on it. Steve Jordan doesn't like to talk much these days, his friends say.

He doesn't have to. More than five decades of music attest to his madman brilliance on the accordion, an inspired fusion of Mexican heritage and Texas rebel rock, on display most Friday nights at the Saluté International Bar in San Antonio.

Born in East Elsa

The instrument in Vienna first known as an accordion scarcely resembles the one today. Several variations popped up independently between 1810 and 1822, the year Friedrich Buschmann's more familiar version appeared in Berlin. It quickly spread in popularity from Germany, France, and Russia to such far-flung places as Korea and eventually Mexico, imported by 19th century sailors and immigrants. Spain's North American colony is where the accordion incorporated elements of música norteña, the language of Northern Mexico and also South Tejas.

During the 1930s, Narciso Martínez and Santiago Jiménez Sr. pioneered the use of accordion in norteña, more familiarly called conjunto. The genre's folksy style and penchant for tales of heartbreak and loss appealed to the often-nomadic Tejano communities, as well as to young musicians like Valerio Longoria, who pushed its borders in the following decades by adding a beautiful rancheras vocal style and elegant bolero beat. Longoria also customized his accordion for a distinctly hoarse sound.

Flaco Jiménez and his brother, Santiago Jiménez Jr., continued their father's tradition in the 1960s, an era when the accordion suffered from massive PR problems. Here was an instrument rendered a joke by most Americans because it was equated with Lawrence Welk, backwoods Cajuns, and painful performances by back-porch grandparents. It was possibly the most unhip instrument imaginable, just the quirky detail egging on someone like Doug Sahm when he drafted Flaco in the recording studio for Doug Sahm and Band in 1973. That was about the time Steve Jordan began turning heads.

The youngest of 15 children, born in 1939 to migrant workers in Elsa, deep in the Rio Grande Valley, Jordan mastered a variety of instruments, including guitar, at an early age. That was a good skill for the undersized child, unable to work the fields because he was blinded in one eye at birth by a midwife's misapplication of eye medication. While in a migrant camp near Lubbock around age 7, he discovered the accordion, with near-immediate proficiency.

In his teens, he organized four of his brothers into a band to play the dances that accompanied the migrant lifestyle; by 20 he'd moved to California, won a conjunto contest, and married a singer named Virginia Martinez. The two recorded together in 1963 as Jordan went on to work the "taco circuit," following farmworkers and cotton pickers. Songs like "Squeeze Box Man" were hits on those circuits, but late in the decade, rock & roll had Jordan's attention, especially a guitarist named Jimi Hendrix. Intrigued, the Texan experimented with using guitar effects such as phase shifters and fuzz boxes on his accordion.

What came out was unorthodox – bright, soulful, bursting with energy. In a word, spectacular. He layered his love of jazz plus rock & roll, country, zydeco, and Cajun over conjunto's conservative format and added lively covers in English. Jordan's untamed rhythms captured the youthful interest of the post-hippie generation in places such as Austin, where he played traditional Mexican dance halls and Guadalupe Street bars, then Austin City Limits.

In 1982, he entered San Antonio's Tejano Conjunto Hall of Fame. Torchbearers like Los Lobos championed Jordan's expertise, while recordings on Rounder and Arhoolie preserved his remarkable style. Cheech Marin used his music on the big screen for Born in East L.A., and his album Turn Me Loose was nominated for a Grammy. Hohner developed the Rockordeon in his honor.

Jordan's innovation didn't come without pitfalls. He walks no line but his own, musically or professionally. Critical of conjunto's once-limited beats, his creative vision expanded it well beyond traditional instrumentation – saxophones, jazz guitar, synthesizers, marimbas. He can be combative in musical turf wars but is expansive and charming in person. His reputation has been prickly, but with audiences he's golden, because that's where he directs his music.

The audience, you see, is what counts.

El Mundo de Esteban

Saluté International Bar is a long name for the cozy venue Steve Jordan calls home every Friday night in San Antonio. It sits on North St. Mary's Street, a South First-like strip teeming with clubs, restaurants, and attendant nightlife. Proprietor Azeneth Dominguez confides that she's discouraged by recent business and considers closing it. That's hard to imagine, since tonight the venue vibrates with anticipation of Jordan's weekly gig.

A dozen regulars filter in and out. Two 30-ish party dolls in tube tops and shorts stay for a beer or two, getting up to dance solo or with a partner when the feeling strikes and the cumbia is right. The feeling strikes often within the sultry confines of the spicy-colored bar, laden with pastel papel picado strung in banners across the ceiling and a homey hodgepodge of neon and posters for the annual Tejano Conjunto Festival. In the crowd of 30 to 40 people is Jordanista Joan Frederick, whose whimsical photography currently decorates Saluté's walls.

"For his 65th birthday, Azeneth surprised Steve with a mariachi band," says Frederick, eyes sparkling at the memory. She's been coming here as long as Jordan's been playing. "He was so happy. When they played, he sang along, knew all the words."

Outside on Saluté's triangular patio, Manny Castillo, drummer for SA roots-rockers Snowbyrd, describes to a New York Times photographer San Antonio's plans for a mural to honor the likes of Steve Jordan. Relaxing at a table next to them is Roy Garza, whose father, Beto, played with Jordan for 25 years. Joe Rodriguez, aka Joe Rod, long embedded in Jordan's circle of friends, strolls by and stops to roll up his sleeve and show off his upper bicep tattoo of Jordan. To Pedro Villarreal, it's just part of the Steve Jordan magic.

Every Friday night, Villarreal drives in from Austin to work the door at Saluté for the gig. He's a lifelong fan of Jordan, one who sought out his music and was brought into the fold. Villarreal wrote liner notes for a Jordan work-in-progress.

"Lots of people who come here to hear Steve are not necessarily accustomed to standard conjunto music," conjectures Villarreal from his stool by the front door. "They want the edgier stuff – the stuff that only Steve Jordan plays. He's a genre unto himself, and he can take a song from any other genre and make it a Steve Jordan song.

"It's Steve Jordan's world, and we're just visiting."

Dream Guardian

At 1:25am, Steve Jordan walks from the parking lot to the stage and hoists the accordion to his compact chest to play the third set, his last of the night. He's joined by his handsome youngblood band Rio Jordan: sons Ricardo and Steve III plus a drummer. On hand is accordionist Robert Luis Perez, who filled in on the lengthy second set while Steve rested outside after a short but spirited first set.

The abbreviated final set includes the only pop cover of the night, Blood, Sweat & Tears' "Spinning Wheel," sung in Spanish three-part harmony, though there were a few calls for "My Toot Toot," the "Louie Louie" of accordion songs. Less than 20 minutes later, the music's over.

At nearly 2am, Ricardo gestures across the bar: El Parche is ready to talk. Don't talk about the past; don't ask about his health.

The elder Jordan doesn't volunteer much as he heads from the club to his SUV across the asphalt with a measured gait, except to say he's been to the doctor, and "they took a couple of spots from my liver. I lost a lot of blood. I just stay in bed. That's it."

He pats the velvet vest over the midnight-blue puff-sleeved shirt he wears, its swirling pattern a reminder of Jordan's old-school upbringing when it comes to dressing the part. He's always been a man of style. The eye patch gives him instant notoriety and mystique. And Jordan knows it. The look is part of the Mexican culture of music, the folk, the modern, the cholo, the pachuco. He took the look and gave it the same treatment as he did the accordion, displayed on a hot summer night in 1977 at a Guadalupe Street club. He pretends with gentlemanly agreement to remember it, but the reference nonetheless pleases him as he climbs into the passenger seat of the truck.

"I've got nine CDs I'm working on now. I hit a little air pocket," Jordan chuckles. "I gotta mix them, but it's already done – 90 songs. I've got my own recording studio, towers to make CDs and stuff. I'm ready to go. [The music] will be there when it has to. The material's right there. Taken seven years to do it.

"It's got a lot of jazz, salsa, rancheras, boleros. Four voices, three voices, Four Freshmen stuff," winks Jordan without the wink. "Horns. I got a synthesizer guitar, and I do all the parts. I'm a jazz-guitar player, you know."

He smiles when asked about his experimental use of phase shifters and fuzz boxes.

"That was the late Sixties, early Seventies," he nods, grinning. He enjoys being reminded of his taking the beleaguered accordion to a new, hip plane. "Nobody was doing that. Not at the time. I have two [new accordions], but they're too tough. The material's not the same. I have to ... ," he gestures tweaking a knob. "That's what happens.

"We were [doing a lot of touring] but the man told me: 'You got to stop, man. You can't continue doing this.' So it stopped me for a while. 'Okay,' I said. 'Fine.'"

The expression that accompanies this statement is pure Steve Jordan, a poker face with a touch of the trickster. In the shadows of the front seat, his gaunt face is copper lined in bronze. Backlit by the blue-white streetlights, he reclines and rests his head against the seat, staring from beneath one iguana-lidded eye.

Suddenly, he's Chac-Mool, one of the supine Mesoamerican stone sculptures found by the Mexican pyramids around Chichen Itza and other Mayan hot spots. Carlos Castaneda called them representations of dream-guards, the ideal protectors of any chosen person, idea, way of life. Steve Jordan reclines perfectly still, then his face splits into a grin.

"That's life, ain't it? I'm still here."

A tribute to Steve Jordan throws down at the H & H Ballroom, 4404 Brandt Rd., on Sunday, Aug. 10, 3-8pm. Performers include Little Joe Hernandez, Los Pinkys, Conjunto Aztlan, Ernie Garibay, Sauce Gonzales and Dimas Garza, Ponty Bone, Johnny Degollado y Su Conjunto, Texana Dames, and many, many more, including a special appearance by Jordan himself. $15.