District Eternity

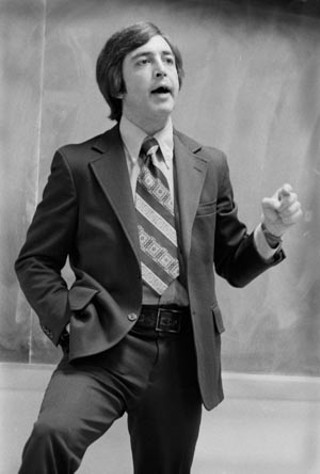

Ronnie Earle on Ronnie Earle

By Michael King and Jordan Smith, Fri., April 11, 2008

Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle, who in December announced his decision to retire at the end of 2008, likes to tell the story of a waitress who came up to his table some years ago and said, "That man over there wants to know if you're the district eternity of Austin." Earle, 66, will step down at the end of this year, to be replaced by Rosemary Lehmberg, the winner of this week's run-off election. That will complete 32 years in office since Earle's first election in 1976 – not quite eternity but a long enough prosecutorial career to suggest that Earle's local influence on law enforcement and the pursuit of justice will not soon disappear.

Certainly Lehmberg will reshape the office to her own perspective. But the man who is now routinely described as "the most powerful Democratic state officeholder" has built a considerable legacy in his three decades as district attorney, and the next occupant will need to be quite determined to clear a space under Earle's long shadow.

For the last few years, Earle has been best known, especially in deep-blue Democratic Austin, as the man who brought down Tom DeLay. Earle's prosecution of the former U.S. House majority leader and his confederates for campaign finance violations is still in progress – if the court actions last beyond this year, Earle says he will offer his pro bono assistance to his successor. But the most important effect of the DeLay indictments, primarily on charges of using illegal corporate donations to underwrite Texas legislative campaigns, was that it made it finally impossible for the scandal-plagued congressman to continue as a national Republican leader.

It's certainly not the first time that Earle, in his role as ethics law enforcer for the state capital county, has indicted and brought low a prominent politician – he is inevitably quick to point out that he has prosecuted more elected Democrats than Republicans, a reminder that through most of those 32 years, there were more Democrats in state power than Republicans (see "Ronnie Earle: Prosecutions of Elected Officials"). But the DeLay case is special, not only because of its national prominence but because it is based on a century-old Texas law limiting corporate and union influence on politics. Earle says that tradition has also become the seed of his next public project.

During a couple of recent conversations in his office, Earle said that while he is not certain what he will do once he steps down – and there has been inevitable speculation about a run for higher office – at least part of his public life will be devoted to speaking out on that subject. "I've got some hopes that I can spend some time and energy advocating for public financing of campaigns and against corporate corruption and for universal health care," he said. "Those are three things that I think are the very most important things that we could do to restore democracy, because if democracy depends on money, it isn't democracy – because then the public is frozen out of the process."

But when Earle reflects on his career, he doesn't dwell on the celebrated (or notorious) public integrity cases, the headline battles with prominent politicians. He is much more eager to talk about his particular notions of what a prosecutor is and does, his perspective on the nature of justice, and his belief in the communal foundations of ethical behavior. As the ground of that belief, he credits his own upbringing amidst an extended family in the small town of Birdville, outside Fort Worth. "It really informs everything I've tried to do – well, not everything, but most of the things I've tried to do as district attorney, especially the most progressive and innovative things that we have done in this office. And the reason is because the law doesn't teach you how to act. ... What I have come to call the 'ethics infrastructure' teaches you how to act. And that is in that work of mommas and daddies and aunts and uncles and teachers and preachers and neighbors and cousins and friends – that's where you learn how to act, not from the law."

In a state better known for prosecutors who act out a Hollywood version of the Old West – convict first, and ask questions later – Earle has steadily attempted to find ways the prosecutor's office can prevent crime before it happens. He's built programs around the concept of "community justice" – including diversionary drug courts, child-abuse prevention, family-violence prevention, community justice councils, and so on – all of them based on the principle that a web of concerned people and community institutions prevents crime much more effectively than exaggerated law enforcement. "Everything I have done," he says, "is based on that principle: The stronger the community, the less crime. That's my basic, empirically provable belief. We've got a remarkably low crime rate [in Austin], one of the lowest of any major city in the country, and frankly, it's because of the kind of city we are. And a large part of that has to do with many of the programs that we have established out of this office."

The Nature of Justice

Earle describes his own life as an autobiography in learning the meaning of effective justice. He recalls Birdville as a tough town where fistfights over real or imaginary insults were inevitable and frequent and Fifties Fort Worth as the seat of local mob violence. "It was called Little Chicago. ... The mob tried to move into Fort Worth in the Fifties, but they were run out because [local crime] was too well-organized. That was a legend that I assume was true, because there were gangland murders all over the place when I was growing up." He and his friends were no angels, but he believes they were kept out of serious trouble by relatives and elders. "My mother had like ... seven sisters and a brother and several half-brothers and -sisters. My father had six siblings, two brothers and four sisters. And I had all kinds of cousins, right? And you couldn't throw a rock without hitting somebody I was kin to ... and you couldn't throw a rock without somebody catching you doing it either. This is where I get my basic concept of the role of community in the regulation of behavior. The regulation of behavior cannot be left only up to the law without sliding into totalitarianism."

At the time, he wanted to become a cop – "the only lawyers I ever saw were like vagrants, hanging around the Fort Worth courthouse" – and thought he might play college football but was a little small for a major college scholarship and instead enrolled at UT-Austin, working his way through. Was it a cultural shift from Birdville? "I thought I'd come to heaven; I really did. To be here with people who could have an argument without having a fistfight, and I thought that was really remarkable – that you could actually do that. And who thought different things. And I saw people with beards and things."

He arrived in Austin in the fall of 1960, on the cusp of a time when the whole country would change. He had become interested in the law and politics, and a paper he wrote in law school ("The Fire This Time: Urban Riots and Ghetto Violence") somehow caught the eye of the governor's office, and he went to work there in 1967. He also got involved in a city of Austin fair-housing campaign, and that led to an appointment as municipal judge, which he calls "the best job I ever had" – because it enabled him to learn much more about the whole community, ranging from students being arrested in protests to police working homicide details – "what it was like, what they were like. I'd known some police officers [back home], and there wasn't a whole lot of comparison. There was a great deal of difference." Moreover, as a judge, he says, he eventually learned that just being "tough" – especially on addiction-based crimes like drug abuse and public drunkenness – was not just pointless; it was counterproductive. "So I started looking," he recalled in a 1980 speech, "for another way to do it."

The judgeship led to an appointment on the Texas Judicial Council, working on revisions to the state Constitution. He resigned in 1973 to run for the Legislature and in his single term achieved his first measurable success at ameliorating the most punitive aspects of drug laws. The previous Legislature had reduced the penalty for minor marijuana possession to misdemeanor status but had failed to make the law retroactive for the hundreds of inmates previously sentenced as felons. Earle persuaded Gov. Dolph Briscoe to create Project STAR (Social Transition and Readjustment), which used executive clemency to pardon inmates and help them find employment. "I don't remember the numbers," says Earle, "but I used to have a certificate from the Department of Labor, because this was the most successful ex-offender rehabilitation program in the United States."

In 1976, Earle resigned from his House seat to run for district attorney, he says, because he's always been intrigued by the idea of "justice" – what it means and how to achieve it. "It's a balance – justice is a balance. The law says that 'it shall be the primary duty of every prosecutor not to convict, but to see that justice is done.' It's not doing justice; it's seeing that justice is done." That first election win was an upset – but over the years since, he's become such an institution that his recent campaigns have been unopposed.

Asked to elaborate on justice in the context of prosecution, he says: "I even have a definition for justice, even though the law does not provide one. I have puzzled over this for 30, well, more than 30 years, because I was puzzling over this even before I ran. ... I have come, finally, to a place where I have a vague idea of what justice might be. And it is the fairness and balance that come from healthy relationships. And so that, of course, raises the question: What is a healthy relationship? And that is one that shares joy, pain, and power."

Rhetoric or Reality

Sentiments like those, expressed regularly in public speeches, have earned Earle both accolades and eye-rolling – and occasionally unflattering nicknames, like "Prosecutor Woo Woo." Earle has plenty of critics, although the loudest have been mostly public officials or former public officials who were targeted by one of his ethics investigations. DeLay famously called him a "runaway prosecutor" engaged in a "partisan witch hunt," to which Earle responded tartly, "Being called partisan by Tom DeLay is like being called ugly by a frog." The most frequent counterattack – from DeLay, former House Speaker Gib Lewis, Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, etc. – is that his decisions to prosecute were "political." The problem with that claim, merited or not, is that it is what any investigated politician is inevitably going to say.

More troubling are the questions about the ultimate effectiveness of Earle's attempts at institutional reforms. To an admirer of Earle's aspirations for community justice, his frequent declarations on the matter can sound like generous, thoughtful, if rather gnomic wisdom. But to more skeptical observers, the grand words can resound too much like unfulfilled rhetoric. Former Attorney General Jim Mattox has personal reasons to distrust Earle, who indicted him in 1983 on a "commercial bribery" charge related to his enforcement actions as AG. Many observers thought it was a strained use of the statute, and Mattox was acquitted ("The jury laughed at Earle and probably would've convicted him instead of convicting me," says Mattox now), and he still believes that Earle was after his job (a claim Earle dismisses out of hand).

Mattox remains understandably bitter, but the two men have since returned to what both call "professionally speaking terms." Beyond his personal story, Mattox has more general and perhaps more telling criticisms. He maintains that Earle's office, despite its hard-nosed reputation, has not been nearly as aggressive as it should have been in rooting out corruption at the Capitol – especially the cozy relationships between the corporate lobby and favorable legislation – and that while Earle has pursued individual malfeasance like misuse of travel funds, "he has never addressed the hardcore issue that truly has our democracy by the throat. I think had I been in his position, I probably would want to more aggressively pursue those interlocking issues."

Equally significant locally, Mattox describes the overall effectiveness of Earle's heralded criminal justice reforms as disappointing. He says: "Ronnie would probably claim the mantle of being particularly visionary and imaginative in the overall setting of policy for his office, and I think that he has experimented with different kinds of prosecutorial procedures. But I don't think they are any more dramatic than applied in a number of different metropolitan counties." Moreover, while also laying considerable blame at the feet of the Legislature and local government, Mattox believes there has been little progress over the years in improving the situation for those most often targeted by prosecutors. "I think you will find the discrepancy that exists in the prosecution of minority defendants and of poor people in Travis County [is the same] that exists in most other major counties. They're following the framework set up by the Legislature and everything else that causes the lack of success."

Earle concurs with Mattox to a degree, responding by e-mail, "The Legislature, responding to public fear of crime, the cultural belief that harsh punishment is our best protection, and the prison-industrial complex, has not always been enthusiastic about giving the justice system the tools we need to solve problems." He said that, in effect, his office is required to work around legislative mandates to address the conditions that cause crime, and he believes he has been successful. He points to the county's "problem-solving courts": "the first drug court in Texas, the first community court in Texas (the fourth in the U.S.), and now mental-health and family drug courts," which both divert people from the criminal justice system and link them up to social services. "All of these courts are nationally recognized as best practices," Earle said, "and we have demonstrated very practical, real results in our community."

Mattox's opinion is echoed by civil rights attorney Ann del Llano, who participated for several years in the Reentry Roundtable established by Earle, aimed at helping former offenders reintegrate into the community. Del Llano says she was badly disillusioned by the results. "I waited [years] to see what tough, systemwide changes Mr. Earle was willing to make within his office, and to date I have not seen him make any systemwide changes in line with the solutions proposed by the Reentry Roundtable. Ronnie Earle continues to choose to incarcerate nonviolent drug users in the face of clear evidence that that is the wrong solution for our community. He continues to hand the lowest-level drug users a felony instead of using the misdemeanor option, forcing them into permanently unemployable second-class-citizen status ... and punishing not only the defendants for the rest of their lives but their children and family, as well. The most recent study shows that Ronnie Earle incarcerates drug offenders who have black skin 31 times more often than people who have white skin – a more racist outcome than any other major city in Texas! In this day and age and in this community, there is no excuse for these choices."

According to the Justice Policy Institute report cited by del Llano, blacks in Travis Co. are 31 times more likely than whites to be incarcerated for drug offenses, a rate much higher than Dallas Co. or Harris Co. The discrepancy is discouraging.

Earle responded in part: "The JPI report is a classic example of a great opportunity for the criminal justice system and community to look at a serious issue from a problem-solving perspective. The issues raised in the report are not just about how we prosecute cases but how we enforce drug laws, including looking at in what neighborhoods we are directing our enforcement strategies." He went on to point at specific, successful projects that have come out of the Reentry Roundtable but argued more generally: "The JPI report says we need to look at the intersection of poverty and unemployment. Poverty and crime are joined at the hip. Poverty not only affects the pocketbook but also the spirit. It sometimes becomes a life in pursuit of the next elevation of the spirit, temporary but deadly, that motivates some drug users, especially of the harder stuff. ...

"So the JPI report points out systemic issues that will require stakeholders (including most of all the public) all across the criminal justice system to address. It would be great if it were just about how we prosecute cases, but it's not; it's how we get out of our silos and get together; now we call that collaboration. I think it is an exciting opportunity to have a great community conversation about these issues. We're ready for it."

Community and Prosecution

Earle is aware of the criticisms, but he believes that he and his office have made significant, visible progress over the years. He undoubtedly has diminished the emphasis upon (and numbers of) death-penalty prosecutions originating in Austin in comparison with other Texas jurisdictions, seeking capital punishment only for those offenses his office – and its unique Capital Murder Review Committee, which advises Earle in such cases – considers the most heinous. More generally, when he is asked about the measurable success of his broader community justice programs, he points not to conviction numbers or similar courtroom statistics but to the relatively low local crime rate. "The proof in the pudding," he says, "is really the fact that Austin has one of the lowest crime rates in the country – probably the lowest per capita. In 1991 we had 49 murders; last year we had 20-some. And the year before, it was 23 or 24." (Recent FBI statistics posted by the city of Austin show Austin with a violent crime rate below the national average and a property crime rate above the national average.) For 2005 (the most recent figures available), Austin ranked as the third-safest large city, based on the per capita violent crime rate.

"And so, the reason for that is that we have taken a real proactive approach: Crime comes from the neighborhoods, so you make the neighborhoods stronger, and you have less crime." Earle relentlessly insists that the whole community is the true foundation of public safety and points proudly to the success of the Community Justice Councils, a structural collaboration among many institutions and officials. "In the mid-Eighties, I got the Legislature to pass a bill creating Community Justice Councils in every community. ... The council consists of 11 elected officials, and then there is a Community Justice Task Force that consists of 18, 19, 20-some-odd appointed officials – like the chief of police, the superintendent of schools, the head of [Mental Health Mental Resources], the head of Child Protective Services ... the people who have something to do with crime. The elected officials are the ones that you would automatically contemplate – the D.A., the sheriff, the district judge, county court-at-law judge, a [justice of the peace], a member of the City Council, a member of the Commissioners Court, a member of the Legislature, a member of the school board. ... They all contribute in one way or another to the quality of life and the safety of the community. So, anyway, the Community Justice Council in Travis County has been the most active in the state. I have been the chair of it since its conception.

"And I think the primary reason for our success at keeping the crime rate low and protecting the quality of life, and the sense of justice issues, is the result of the extensive collaboration and cooperation that we have been able to achieve – and when I say 'we,' that's not the royal 'we' – that's all of us, all the people who are in these positions."

Speaking more personally, Earle describes the work of Assistant District Attorney Eric McDonald, assigned as a "neighborhood D.A." to Downtown and the near Eastside. McDonald learned that state-jail inmates, upon release, were being bused Downtown and dropped off without any kind of follow-up or support system – with a resulting spike in the crime rate, everything from vehicle burglaries to violent assaults. "So, Eric started, on his own; he would go out and meet with these guys before they got released, individually, one on one. And would say: 'You got a place to stay? You got a job?' ... You know, those kinds of things: 'Can we help you? How can we help you?'

"And so, what happened was, the day they'd get out, a police officer pulls up in a police car, and they get in, and the police officer gives them a ride to a halfway house somewhere other than Downtown. And it's the first time, for many of them, that they've been in a police car without being arrested. And so the result of that was that the crime rate Downtown just tanked; it went way down. Real simple." (According to information provided by the D.A.'s office, in response to McDonald's efforts and those of his Downtown successor, David Laibovitz, Downtown burglaries of vehicles declined 10% in 2003, 32% in 2006, and an additional 15% in 2007.) "This is what is known as community prosecution," Earle concluded. "We are considered probably the bellwether office in the country for that."

Justice and Community

In short, Earle is quite proud of the record of his office in both crime-fighting and building community, since he believes they are two different forms of the same thing. His conversation inevitably comes around to the relationship between justice, public safety, and freedom and his belief that these are all interrelated and a question of balance. "My intention has been to achieve the maximum amount of freedom consistent with public safety. Okay? And so these programs have been dramatically successful to the point where they are considered national models, and this office is considered a national model. That's the cart and the horse. The programs are very successful, and because the programs are very successful, this office is a national model."

On the issues underlying his most famous prosecution, that of Tom DeLay and the corporate funding of campaigns, Earle can still get angry over the 1886 Supreme Court case (Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co.) that indirectly ended in corporations being granted "personhood" and thus equal protection with citizens under the Constitution. "That was just dumb," Earle growls, noting that the doctrine originated in no more than a clerk's note, not a court opinion. "Since then, it has been the law, but it all came about as a footnote. ... Here we are, just blindly following this dumb thing that says corporations are 'persons.' Which is just breathtaking."

The populist 1905 Texas law under which DeLay was prosecuted was intended to head off expanding corporate influence. "They were trying to stop the railroads from buying members of the Legislature – that's the short answer," summarizes Earle. "I mean, there's probably much more erudite and therefore obtuse ways of saying that, but that's what the deal was. And it's really not that much different now. ... In those days, it was mostly fights between business and labor, but also a lot was beginning to be fights only between big businesses – and now that's all it is."

Asked if he believes his personal, communitarian approach to justice in Travis County will survive his retirement, Earle is noncommital. "That is up to the people of Travis County," he responds. "What I've tried to do is to reflect what I thought was the very best of the people of this community. ... I think it is up to the community. It is up to the public to demand of the person that they elect to see that justice is done – because that's what the law says the duty of the prosecutor is. The law says it is the duty of the prosecutor, of every prosecutor, not to convict, but to see that justice is done. So all the public has to do is demand that the prosecutor do his or her job.

"Her job, as it is beginning to be."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.