In Your Facebook

Do social networking sites strengthen communities or the class divide?

By Jon Lebkowsky, Fri., Feb. 29, 2008

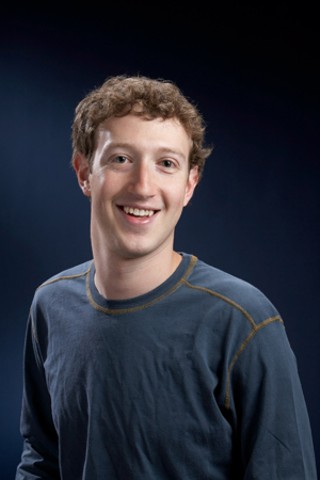

Harvard dropout and Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg famously disavows money as motive for the work he's doing. He eschews the trappings of success – he's walking or biking to work, hanging out in jeans and hoodies, living in a barely furnished apartment in Palo Alto, and devoting all his time and attention to the company he's building. He'd rather "make revolutionary things," he says, than sell Facebook to someone like Yahoo!, despite offers reportedly as high as a billion dollars.

If Facebook is a "revolutionary thing," it's not because the concept or the technology is new. It's not that far from J.C.R. Licklider's 1968 vision for the Internet, of a "common medium that can be contributed to and experimented with by all." If Facebook is revolutionary, it's because it's the right technology at the right time, with a high rate of adoption by the right kind of audience to make it much more than a bunch of faces and profiles. It's an aggregation of the social graphs of an elite group of young, so far mostly American, cultural creatives. It was inherently established as a platform for the elite at its launch, offered only to the best and brightest young people, students enrolled in America's Ivy League universities. These founding members, privileged and influential, connected via Facebook's social technology to "show and tell" their passions, fascinations, casual thoughts, and weird quirks. Boone Putney of Soleer Web Solutions says: "The Facebook team was ... wise to limit membership. In the early Facebook years, it was labeled 'MySpace for Elitists,' because you had to have an active college/university e-mail address. This led many of my female friends to feel more secure and choose Facebook over MySpace. I guess it's because they could be assured that although the random guy contacting them might be a total creep, at least said creep had received some sort of college education." Facebook felt smart and safe.

So, by the time Facebook opened to users outside academia, it had established its elite cred vs. the much larger MySpace's street cred. Mashable, a site for news about social-network platforms, ran an interesting comparison, an article titled "Facebook Users vs MySpace Users: We Report, You Decide" (www.mashable.com/2007/06/26/facebook-users-vs-myspace-users), listing most popular artists on MySpace vs. most popular artists on (a subset of) Facebook. No. 1 for Facebook is soft rocker Jack Johnson vs. rapper Akon on MySpace. No. 2: Coldplay at Facebook vs. Panic at the Disco at MySpace. No. 3 is Sublime at Facebook vs. rapper T.I. at MySpace. Later, at No. 7, it's Green Day on Facebook vs. Fall Out Boy at MySpace. The list goes on, but you get the point: The demographics are widely divergent, not unexpected since Facebook started as an Ivy League hangout and the MySpace population is a funkier mix of high school students, musicians, and all-collar classes of adults. The Mashable piece was inspired by danah boyd's exploration in a piece, published online at her website, called "Viewing American Class Divisions Through Facebook and MySpace." Class divisions in the U.S. are more about lifestyle and culture than income, and where the two most popular social-network platforms are concerned, the division (at least among teens) is between the Goody Two-shoes from families that emphasize education and going to college – those tend to prefer Facebook – and the various others who don't fit the "dominant high school popularity paradigm" (e.g., "Latino/Hispanic teens, immigrant teens, 'burnouts,' 'alternative kids,' 'art fags,' punks, emos, goths, gangstas, queer kids") – those favor MySpace. She categorizes these two groups, respectively, as "hegemonic teens" and "subaltern teens," but she notes that this is a sloppy characterization. The reality she's seeing is more complex and requires more research. She's troubled by what she's seeing and doesn't quite have words for it. "There's something so strange about watching a generation slice themselves in two," she says, "based on class divisions or lifestyles or whatever you want to call these socio-structural divisions." She continues:

"I feel as though the implications are huge. Marketers have already figured this out – they know who to market to where. Policy creators have figured this out – they know how to control different populations based on where they are networking. Have social workers figured it out? Or educators? What does it mean that our culture of fear has further divided a generation? What does it mean that, in a society where we can't talk about class, we can see it play out online? And what does it mean in a digital world where no one's supposed to know you're a dog, we can guess your class background based on the tools you use?"

Are we watching a generation "slice in two," or are these sites making visible, and emphasizing, a division that already existed? Before the social Web, most of us didn't know we were part of social networks. We had friends, and we knew that our friends might know people that we don't, but most of us never thought to chart or analyze those relationships. Now we can make our networks visible and explicit and touch base with them every day through sites like MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, etc. Are we any better off than we were before? Do we know the people in our networks any better than before? Can we manage more relationships than we did before? Looking at the darker side, will we be exploited by the operators of network platforms? Will everything we say and do actually, no foolin', become part of our "permanent record," tracked by Big Brother and his henchmen? Will the Internet become the next television, an instrument for programming consumers, pretending to be a channel for art and entertainment?

Yes to everything. Yes, we're better off; there can be tremendous value in network exchanges and far more potential for productive collaboration and resulting innovation. We probably do know most of the people in our networks better; we can connect to them casually every day, like the Internet was a massive water cooler where everybody, and I mean everybody, can hang out. Can we manage more relationships? Sure, but that's deceptive: We have the technology to manage more, but that doesn't mean we can manage all the relationships that we "add" at any qualitative level. All the social-networking platforms caution you to add as friends only people you really know well. Real value depends on quality, not quantity, of relationships.

And yes, some people will be exploited, but network platforms that exploit will lose trust, lose users, wither, and die. Yes, everything we do online is recorded somewhere and probably retrievable somehow by somebody, and the intelligence agencies are probably crunching some of your data somewhere sometime. There's never been any real expectation of complete privacy online. On the other hand, it's impractical to think that Big Brother is watching. His eyeballs and his interests are constrained by an economy of attention, if nothing else. And the Internet's already become the next television, but it has a bazillion channels, many with ads, and many of the ads that do appear are unobtrusive. Austin tech consultant and entrepreneur Venki Iyer told me, "We all just need to get used to surveillance and practice good sousveillance [watching the watchers]."

Questions of exploitation, ownership, and control can be crucial for online community platforms. Seminal online community the WELL (Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link) was dedicated to free speech and mindful of the rights of members to have ownership of, and responsibility for, their conversations and the communities they were forming. Whole Earth's Stewart Brand wrote a guideline for the WELL that began, "You own your own words," and went on to equate ownership with responsibility. The WELL had managers, but they were barely tolerated – the community was, and is to this day, fiercely independent. This is arguably why the WELL has rocked on, profitably, for more than 20 years. The WELL inspired other online communities that were similarly respectful of their members, understanding that their contributions and interactions are the real and only source of value.

Web 2.0 is all about user-generated content and participatory environments. If you're an entrepreneur building a social environment that depends on its users, how far can you go in monetizing the value of their contributions? If you're gathering a significant database of user data, is it your intellectual property or theirs? Do your users have the right to control the use and distribution of their content and their data? Do they have a right to tell you how the online environment should be structured?

Facebook is clearly operated with big profit goals, as emphasized in Tom Hodgkinson's recent Guardian article "With Friends Like These ...":

"Facebook is another uber-capitalist experiment: Can you make money out of friendship? Can you create communities free of national boundaries – and then sell Coca-Cola to them? Facebook is profoundly uncreative. It makes nothing at all. It simply mediates in relationships that were happening anyway."

I talked to several Facebook users, and nobody seemed to feel exploited, though Julie Gomoll of LaunchPad Coworking had a love/hate relationship with Facebook and ambivalence about her participation there. "I feel obligated to do it but resent the time it takes," she said. "It's not a primary avenue [for me] for anything. It's purely supplemental. I don't want any more pokes, or presents, or anonymous greeting cards. I do like that I can aggregate a bit there – have my tweets [Twitter posts] magically show up, for example. And the group functionality is much more useful than the equivalent on LinkedIn."

Bijoy Goswami, developer of the Bootstrap Austin community, which has both face-to-face and virtual aspects, says that "Facebook truly gets it about social interactions and how we want to map those online." However, he says, "just as with Google, they will need to figure out their revenue model without compromising what they've created, and that will be a challenge. The first attempts at this have been not so good, so hopefully they will figure it out."

In 2006 Facebook added a News Feed as a home page centerpiece that displayed all the activities in the Facebook member's network ... e.g., specifics about friends joining groups, attending events, adding notes and photos, posting to walls, etc. The News Feed reinforced the sense of Facebook as a living, breathing, active community, but there was controversy. Some complained that the News Feed was just so much clutter, and others saw it as a violation of privacy, though only "friends" could see, and the activities displayed were otherwise findable on the site. Convinced that the News Feed was inherently a good thing, Zuckerberg didn't budge despite petitions and Facebook-based groups opposing the new feature. He conceded the privacy issue, however, and offered a feature allowing members to control which activities show up in the feed. He apologized for offering the feature without such a control in place.

The News Feed controversy was minor, though, compared to the fracas over Beacon, a system that would display member activity from partner sites external to Facebook. For many, there's something inherently creepy in making the details and patterns of their purchases and preferences known without their permission. It was so creepy that MoveOn.org created an online petition and (of course) a Facebook group to organize dissent. Fifty-thousand members signed on right away. This led to another apology from Zuckerberg, and Beacon was revised to become an opt-in program – at least for publishing the data; it's not clear whether Facebook's still collecting it.

I said above that Facebook users I've been talking to don't seem to feel exploited by the system. They don't seem concerned about these privacy issues, either. The 50,000 explicitly opposed to Beacon make up less than 10% of Facebook's 60 million users. The Facebook members I spoke with were pondering the increasing demands for their attention and how well those demands align with their priorities. Chris Boyd of Midas Networks told me that he liked Facebook better before they opened the application programmer interface. As a result of this highly publicized recent move, hundreds of developers have created new applications for the site, and each new application is a potential time-suck. Says Boyd, "I seem to be getting a steady and increasing stream of requests for zombies, beers, and movie-related cruft. I suppose that if I made Facebook a larger part of my life," he says, "I might find these enjoyable, interesting, or amusing. But I'm not willing to spend that much time on it, since I get much more interesting content over old-fashioned mailing lists that are tightly focused on topic." On the other hand, Austin musician Heather Gilmer (www.fiddlista.com) says she gets some value from the various Facebook applications. "All those silly toys on Facebook let me and my friends stay on each other's radar," she says, "even if we don't really have a whole lot to say to each other at the moment, and have offered a way to gradually get back on closer terms with people I'd been completely out of touch with before."

Behind the toys and the pokes, the shares and the connections, is there real, in-depth collaboration and community on Facebook? One member opined (in a Facebook group I set up for metadiscussion), "The group application of Facebook is one of the weakest around." Another user, a friend of mine from the early days of the WELL, said: "The forum software is really clunky – but there are enough people on Facebook that it gets used. There's enough traffic to make it interesting." Austin Realtor and blogger Dee Copeland notes that there are "too many active groups on Facebook. Anyone can start a group and then leave it to die," she says. "I think groups should be shut down if they're inactive for 60 to 90 days. They have people join, but there's no value beyond being able to see who else is in the group."

Chris Boyd puts Facebook in perspective: "In the late Eighties, it was an AOL address. In the mid-Nineties, it was a home page. In the late Nineties, it was a website. Then it was a blog. Now it's a MySpace or Facebook page." Technologies are constantly evolving, and so are user preferences. This works against long-term commitment to any specific platform, and there's always been tension between the vendors' desires to monetize and profit from their applications and platforms and the consumer's need to feel safe and empowered and to trust that platforms and environments won't exploit their participation.

There's also a tension between producers of profitable proprietary systems and advocates for open standards and architectures that support a high degree of interoperability and a seamless user experience. Some envision the Internet and the Web as an operating system that emphasizes sharing and has few barriers. The vision is not just technical; there's also the sense of an open social-operating system and platform for work as well as play. There are discussions about "Identity 2.0" and data portability – where individuals have more control over their data and carry it with them wherever they go.

The Internet itself is a vast commons that nobody owns or controls, an environment that persists through the cooperative efforts of many players, large and small. It's best to avoid hubris. America Online founder Steve Case once told Bruce Sterling that the Internet was a "seed community" for his platform. However AOL ultimately faded. It's still there, but hardly the force that MySpace and Facebook have become, and as large and influential as those platforms might be, they're still not dominant. And North America no longer dominates – there are twice as many Internet users in Asia and a hundred million more European than North American users. Overall, there are 1.3 billion Internet users today, compared to 110 million for MySpace and 60 million for Facebook.

Companies have been trying to figure out how to make money on the Web since Paco Nathan and I first launched FringeWare Inc. in 1992. Current thinking is that the advertising model can work. It didn't quite work in the 1990s, but adoption's way up, and the experience of media is increasingly happening online – Rob Campanell of Blastro says that, for today's kids, watching television is something their parents do. Companies like Google, Yahoo!, Microsoft, MySpace, and Facebook are all well-positioned as long as they get the ad thing right and manage to sustain their large established user bases. The rest of us don't care, we just want to do what we do, and as the social Web evolves, what we do increasingly is interact, collaborate, cohere, visit, talk, share, love. And we'll do that with e-mail, blogs, wikis, communities ... MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn, Flickr, Yahoo! 360, Upcoming, YouTube, wherever we find the connections that mean something.

Mark Zuckerberg gives his keynote address on Sunday, March 9.