Snake Charmer

Ray Wylie Hubbard ain't afraid of you

By Margaret Moser, Fri., June 23, 2006

The wooden sign on the east access side of I-35 just north of Exit 210 is easy to miss. Not that the big black letters on weathered white paint don't read clearly: Snake Farm, 28 miles. It's hokey Texana, sure, and a ways from Ray Wylie Hubbard's Hill Country home outside Wimberley, but it's also damn sure a reminder that screw you, this is Texas.

Snake Farm is also the title of Ray Wylie Hubbard's new CD. Though Hubbard long ago shed the skin of his Seventies signature "Redneck Mother," the sinewy Snake Farm possesses a rattler's bite. His slow-burn vocals rasp with grit, the lyric venomous. Snake Farm ambles down a familiar highway with an hombre that's had a conversation or three with the devil.

Talk about long, strange trips. Hubbard's seen it all and lived to write the songs. Born in Hugo, Okla., he grew up in nearby Soper before relocating at an early age to Oak Cliff in Dallas, where he cut his teeth on pre-British Invasion rock & roll and fell under the spell of folk music. In his 20s, he owned a club in Red River, N.M., but with youthful wanderlust pumping in his veins, he traveled to the troubadour's heart of Texas, just in time for the Sixties to bleed into the Seventies and a long, tough fall from grace.

"I need to get me, I got to find me, I got to have me, a little peace in my heart," he sang on 2001's Eternal and Lowdown, but really, he'd already found that peace by then. He learned from looking back at his life and knowing it can only be lived by moving forward. For Ray Wylie Hubbard, the lesson paid off in spades and clubs.

Redneck Mothers & Blues Fathers

For a man whose songs have become Lone Star anthems, music didn't play a prominent part in Ray Wylie Hubbard's childhood. He recalls the hymns sung on Sunday visits to the Baptist church with his grandmother in Soper and the baptisms down at the Red River. Yet aside from an occasional rendering of "One-Eyed Sam the Gambler" from his father, music wasn't a force in the youngster's rearing.

That all changed when he was 8 years old, and his father Royce transferred to the Dallas suburb of Oak Cliff. His father continued working in the school system at Benito Juarez, and his mother Helen started working for the first time, getting a job at Western Union. Meanwhile, the face of popular music was changing, and the common expression of it was the radio.

At Adamson High School, Hubbard moved among remarkably talented classmates, including Michael Martin Murphey (a cheerleader at school assemblies) and B.W. Stevenson. The clean-cut folk music of Peter, Paul & Mary; the Chad Mitchell Trio; and the Highwaymen ruled the day, inspiring him to get his first guitar. Learning genre standards like "Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley," he met like-minded folkies named Rick Fowler and Wayne Kidd. Playing covers from bands such as the Kingston Trio took on a different aspect when Bob Dylan came on the folk scene. "I noticed songwriting and songwriters like Woody Guthrie," Hubbard recalls. "The floodgates just opened."

A notice on the high school bulletin board lured Hubbard and his two friends into playing a summer resort. Dressed in matching striped shirts, the three took their guitars and hopped a Greyhound bus for New Mexico – a 26-hour ride. That's when Hubbard got his first dose of music business reality: The job wasn't all in the playing.

"Our job also entailed wrapping potatoes in tinfoil, sweeping, cleaning up, and washing dishes at night," Hubbard chuckles. "We were the hired help, but it was a great experience. We slept under the stairs of a cinder-block house."

College called that fall, but the next summer Hubbard and Fowler packed up their instruments and took off in a Ford to sing for their supper in Red River and Colorado. "We're the Texas Twosome," they'd announce. "Can we play for a hamburger and a place to stay tonight?"

It was a satisfying gig for a carefree young man in the late Sixties, who, along with his bandmates, opened a club in Red River called the Outpost. Serving no alcohol, the venue gained success with the tourist crowd as well as being a whistle-stop for musicians traveling the Texas-Colorado folk circuit. Some of his old classmates like Murphey and Stevenson showed up, as did an East Coaster named Jerry Jeff Walker and a trio called Frummox, with Steven Fromholz.

The Outpost cultivated a reputation for late-night jams, and Hubbard responded with dry humor. That reputation and his sense of the absurd served him well. One of his songs, "Redneck Mother," caught the ear of audiences and other musicians, particularly down in Austin where the Checkered Flag, Castle Creek, and the old Saxon Pub burned oily midnight stories and songs.

Written as a lark, the raucous, tongue-in-cheek lyrics and bobbing melody were even more irresistible after a few beers. The opening line was enough to send any audience into paroxysms of laughter and hooting. "He was born in Oklahoma ..." Hubbard began, and by the time he got to, "He's 34 and drinking in a honky-tonk," crowd volume tipped the scale, beer bottles banging on tables as they hollered: "KICKING HIPPIES' ASSES AND RAISING HELL!"

Hubbard took advantage of the free-flowing circuit to score a gig for his band in Omaha, opening for Muddy Waters.

"I called up the owner, who said, 'It only pays $50,'" remembers Hubbard, unholstering another anecdote from a seemingly bottomless well. "'I don't care,' I told him. We drove from Dallas to Omaha by way of Red River to get the bassist. We got there as Muddy was doing his soundcheck, so we stood around waiting. Then Muddy comes by and looks at us, 'How long you supposed to play for?'

"We looked around and said, '45 minutes.'

"'Do 44. Don't do 46,' Muddy warned and walked away.

"That's when I learned never ever to go over time as an opening act.

"After the show, we were sitting around the office getting paid, and, all of a sudden, Muddy goes, 'They loved me, that audience down there. Ya oughta give me a bonus.' The owner gave Muddy an extra $200. After my son Lucas played with me at Willie's picnic last year, he walked offstage and said, 'They loved me. You oughta give me a bonus.'"

Too Much Cosmic, Not Enough Cowboy

Even in its infancy, 1973, Austin's outlaw country scene was fractured. "There's too much cosmic and not enough cowboy" opined a long-forgotten local 45. Doug Sahm, Rusty Wier, Alvin Crow, and Freda & the Firedogs already claimed the state capital as home. Other acts immigrated here as fast as they could.

"If you step back and look at it, that whole scene really was progressive," Hubbard reflects. "Willie Nelson moved here and brought Mickey Raphael, a blues harmonica player. Jerry Jeff [Walker] was a folk singer, and he brought in John Inmon, a rock & roll guitar player. Michael Murphey was a folk singer, who added Herb Steiner on steel guitar. There were also the more underground guys like Blaze Foley, Townes Van Zandt, and Guy Clark.

"I was with Three Faces West, and we added drums and electric bass to our folk thing. It may have been an illusion, but I thought of us as a folk-rock band. 'Redneck Mother' was a joke to play every now and then. Then Jerry Jeff cut it."

Walker embodied the boozing gonzo buckaroo of the day and recorded "Redneck Mother" on his Viva Terlingua LP in late 1973. More than Michael Martin Murphey's groundbreaking Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, Doug Sahm's Doug Sahm and Friends, or Willie Nelson's Shotgun Willie, Walker's live breakthrough bottled the emerging confab of country, folk, and rock that didn't just raise the bar, it tipped it over, beer and all.

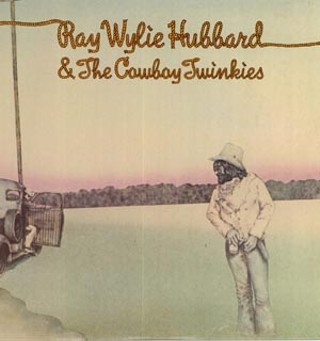

"Redneck Mother" wasn't Hubbard's most successful song until after Walker covered it, though it was his best-known. A little ditty called "Muddy Boggy Banjo Man" was the B-side of Larry Groce's novelty 45 "Junk Food Junkie" in 1975, going gold and introducing Hubbard to fast-spent royalty checks. (Groce, for his part, now runs Mountain Stage for NPR.) More importantly, perhaps, "Redneck Mother" paved the way for Hubbard's much-loved Cowboy Twinkies.

"The much-loved, misunderstood Cowboy Twinkies," Hubbard corrects. "What we lacked in talent, we made up for in attitude. But we were really happening."

That's an understatement. Drummer Jim Herbst, guitarist Larry White, bassist Clovis Roblaine, and Hubbard's longtime friend and collaborator Terry Ware put on explosive live shows that are now the stuff of legend. A typical Twinkies set was as likely to include Led Zeppelin as Merle Haggard and layered with Hubbard's own tunes. The audiences loved it, but the labels ignored them. Frank Zappa's imprint, Discreet, flirted with the Twinkies, after which Hubbard had a misunderstanding with Atlantic Records' Jerry Wexler as drinking and drugging in the band worsened ("A Man and a Half," Music, December 1, 2000). The Twinkies' rawhide rock & roll spirit twisted the progressiveness of their country into a sound that would much later be called "cowpunk," though you'd hardly know it by their one and only recording, an album on Reprise in 1975.

By the time it was released, Ray Wylie Hubbard & the Cowboy Twinkies was such an overproduced, undernurtured recording, it "broke our hearts," laments Hubbard. "Girl singers on every track. We'd felt good about what we were doing. It wasn't all 'Redneck Mother'; there were cool songs. The label did stuff to it to get it on country radio. When we got our advance copy on cassette, the band and I were in my driveway. We played it and heard the steel guitars and background singers and started crying. My mother got home from work, saw us, and said, 'What are you doing?''Listening to our album.'

"This was our chance to prove what we had, and that was what they did. I called a lawyer friend of mine and asked, 'What should we do?' 'I suggest you start drinking,' he told me, so I did. For the next 20 years."

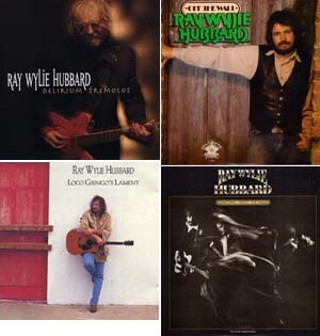

Hubbard isn't exaggerating. The Cowboy Twinkies broke up. He went with other bands for a while – the Gonzos, Bugs Henderson. He halfheartedly recorded Off the Wall for Willie Nelson's label but admits "things weren't happening. At one time, I thought cocaine was the answer to my drinking problem, but it gave me booze legs. Writing wasn't something that I was doing a lot of."

Some of that had to do with audience expectation that Hubbard was the character in "Redneck Mother" on and off stage. The song was his calling card, his ticket to ride, a dead weight on his shoulders. It's a scenario familiar to many artists who create one image in their youth and find it doesn't age well. By his 30s, Hubbard was thought of as a cosmic cowboy one-hit wonder.

"Yeah, 'Redneck Mother' was an albatross, especially when Urban Cowboy came out," sighs its author. "People expected that rowdy Jerry Jeff Walker stuff. I don't know that I was conscious of it being an albatross, but the music scene in Austin really changed. Maybe it wasn't an albatross. Maybe the gigs just weren't going well.

"After my dad died, I couldn't drink safely. I'd tell myself I'd just have two beers, but I'd go way beyond that. My dad had left me some money, and it was gone. I was going with a girl who was trying to get me into recovery. She was giving me little hints like, 'You're a bad drunk.' I didn't really know Stevie [Ray Vaughan], but I'd run into him at Riverside Studios. He'd gotten sober and was speaking to some people at a meeting.

"After the meeting, I took some time to talk to him and got a little hope that maybe I didn't have to live like this. I got into recovery and started doing what I was supposed to do on a daily basis. It's still foggy to me. I really don't remember how it happened. I really don't. But it was powerful to me that he took the time to help me.

"I was 41 years old, and I'd burned every bridge I'd slept under," says Hubbard with a frank look. "What did I really want to do?"

Dust of the Chase

Recovery and cleaning up are a bitch. Often, you have to separate yourself from longtime friends, habits, and places to keep up the resolve. Having a clear head isn't all it's cracked up to be, at first, when you're not sure what to do with yourself, your time, your life. Where do you go? How do you have fun? For musicians, sobriety can be frightening. Will one hit off a joint send you back down old paths? Who's there to help you keep strong when the demons return?

Sometimes it's a blinding flash leading you out of the darkness, the bolt of lightning. Sometimes it's a slow recognition that life is still good. For Hubbard, it was all of that.

"It's like I was in a plane crash and baggage was everywhere," he reveals. "And all I had in my head was the black box, running all the time. Guilt. Shame. Remorse. Resentment. Once I got clean and sober and got the baggage out of my head, I came out of the fog.

"I developed a songwriter consciousness. That's when I realized I needed to find out more, about publishing and accounting, to record an album and be able to give it to them while looking them in the eye. Even with the Cowboys Twinkies, it was like, 'Here it is,' and I'd be wincing. I'd made excuses for every album I'd ever done, but when I did Loco Gringo's Lament in 1994, I was like, 'Here it is. If you like it, great. If you don't that's okay too.'

"It was the way I wanted to hear it."

With a renewed sense of purpose, Hubbard found guidance in Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet and James Allen's As a Man Thinketh. "I am lost in the dust of the chase that my life brings," ran a line from Loco Gringo Lament's opening cut, "Dust of the Chase," but that dust, like the mental fog, was clearing. The album, recorded for now-defunct San Marcos indie Dejadisc, took him down a new path, followed by Dangerous Spirits for Rounder Records imprint Philo in 1997, each recording twisting his new path more crooked than a stick in water.

"One thing I needed to do was play guitar better," points out the songwriter. "It may sound contrived, but I wanted to take guitar lessons. I'm 41 years old, I should be embarrassed. But like Rilke says, 'Fears are like dragons guarding our most precious treasures.' Once I became aware of what these fear and doubts were in my head, I could do the opposite and start to improve. So I called up an old friend and asked him to teach me how to finger-pick. Without those dragons, I found the treasures on the other side.

"Somewhere in there I realized that songwriting was inspiration plus craft. Inspiration is the great, 'Aha! Aha! That's a great idea for a song!' The craft is to make it fit the laws of music. The thing I learned is to keep learning new things, so I got a mandolin and wrote three songs on that. I discovered open-G tuning and wrote some songs with that. Then I discovered open D. Then I discovered bottleneck slide, and that really opened up things. What I learned was that I needed to learn new things."

Learning new things reaffirmed Hubbard's knack for wordplay, as well as his ear for a sharp melody. He reintroduced familiar characters – the fallen, the faithless, the lost, the redeemed. Hubbard brought producer Lloyd Maines aboard for 1997's Dangerous Spirits, 1999's Crusades of the Restless Nights, and 2000's Live at Cibolo Creek Country Club, recording experiences he treasures.

On a roll, not letting any daylight whatsoever burn, Hubbard next turned to Gurf Morlix to produce 2001's Eternal and Lowdown, and two years later, Growl, off which his next anthem, "Screw You, We're From Texas," was born. It's the Lone Star tribute to Texas talent, with Hubbard asserting, "'Cause we got Stubb's and Gruene Hall and Antone's, John T's Country Store. We got Willie and Jacky Jack, Robert Earl, Pat, Corey, Charlie, so many more ... Our Mr. Vaughan was the best that there ever was, and no band was cooler than the 13th Floor Elevators, so screw you, we're from Texas."

"When we recorded the Slaid Cleaves song 'Born Again' on Growl, we had Slaid, Patty Griffin, Bob Schneider, and Eliza [Gilkyson] singing," grins Hubbard. "At the very beginning of that song, there's a cough. We left it on there and sent it to the record company. They e-mailed us back and said, 'There's a cough on there.' Gurf replied, 'Yes, it's Eliza, and if we tried we couldn't get a better cough.'"

The Other Snake Farm

A wooden sign just off the porch of Ray Wylie Hubbard's spacious log cabin says "Snake Farm." It was placed there while shooting the title track's video, a moody, arresting piece of work directed by Tiller Russell. Hubbard points it out after returning from lunch at the Cypress Creek Cafe in Wimberley. His boots scuff up the steps to the place he calls "Mount Karma" as his wife Judy and son Lucas follow. A white-furred creature flies out of the doorway, their dog Angel. She wags her resplendent tail and greets the family happily.

You might say Judy was Ray's reward for cleaning up his offstage act. They've been together almost 20 years because she stuck around after their first date. The nearly penniless Hubbard picked her up in a borrowed truck, then took her to see a wrestling match at the Dallas Sportatorium, "because I knew all the wrestlers and could get in free." When she agreed to something to eat after the match, he drove them to the Longhorn Ballroom where Rusty Wier was performing, walked her through the backstage, and steered her to the band deli tray. She married him anyway, and their son Lucas was born 13 years ago.

The rustic Mexican decor of the cabin suits Hubbard's music, smooth and cool like the saltillo tile floors, earthy like the lanky logs. Judy's background as a mosaic designer show in touches like her red-and-yellow tile sink, while her head for business keeps his schedule full and details in place. Lucas, whose playing burnishes Snake Farm's "Old Guitar," darts off to hang out with a friend. Resting in the chestnut leather nailhead couch, Hubbard runs the "Snake Farm" video and later shows the equally amazing "Resurrection" with Ruthie Foster's mighty vocals.

"I try to live with spiritual principles. I don't always succeed, and I don't follow a certain set of beliefs," he confesses. "I'm turning into a cantankerous old coot, but I have rock & roll roots. It's that freedom from fear that I can write 'Snake Farm,' or 'Wild Gods of Mexico,' or 'Kilowatt.'"

It's also the quality that makes Hubbard admired by a younger generation of songwriters from Slaid Cleaves and Cody Canada to Jack Ingram and Hayes Carll. For its part, "Snake Farm" has all the earmarks of a classic Hubbard composition, maybe tough enough to stand up to "Redneck Mother." That song's longevity just keeps on; a live version by the Gourds features Hubbard as a guest, and the audience whooping back: "KICKING HIPPIES' ASSES AND RAISING HELL!"

"We'll probably go back at the end of the year and redo Dangerous Spirits and Crusades of the Restless Nights. We'll redo them like we did 'Resurrection,' with Gurf and George and Rick. If that works out, we might go back and do the Cowboy Twinkies album the way I'd like to do it."

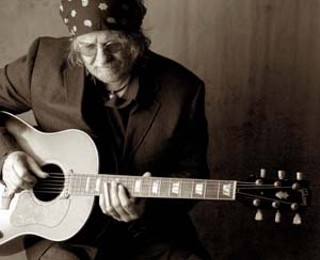

Ray Wylie Hubbard leans forward, hands folded over his denim knees as he finishes his thought. An indigo bandanna rests low on his forehead, his deep brown eyes thoughtful behind the round wire-frames. He doesn't seem to be aware of talking aloud, and maybe he's just talking to himself, nodding.

"I've still got a bunch of stuff to get done." ![]()