Southern Destroyer

Barry Hannah at 60, in Oxford, and on why -- despite the energy drinks -- he's not feeling up to saving American fiction right this very minute

By Shawn Badgley, Fri., Feb. 21, 2003

The Square

Now there is something for tomorrow. What are women like? What is time like? Most people, you might notice, walk around as if they are needed somewhere, like the animals out at the shelter need me. I want to look into this.

-- "Nicodemus Bluff," Bats Out of Hell, 1993

They built the Lafayette County Courthouse in 1840, but it was scorched along with most of this town square -- churches and storefronts and everything -- by the torches of Gen. A.J. "Whiskey" Smith's 14th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment in 1864. They restored it in 1873, and it was immortalized a half-century later in the fiction of a failed poet named William Faulkner. It's a flawless, solid, Greek Revivalist thing, the rock rolled away from the tomb of a resurrected people. It stands still but feels like it's everywhere. If it's not a symbol of justice -- and the area's history tells us that it's exactly not -- at least it's the symbol of a place burnt and rebuilt.

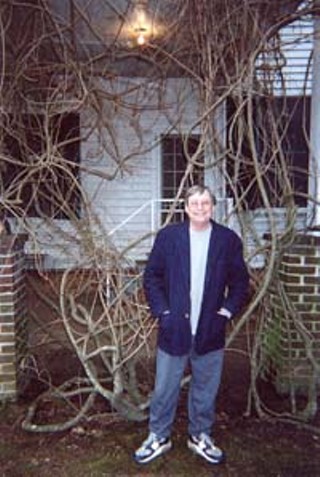

Across the street from the courthouse and a few doors down from the much younger but equally renowned Square Books stands a shorter man, mostly, but standing up straight in conversation with a taller one. He's laughing. He turns slightly to avoid the wind. It's brisk in Oxford, Miss., and he's wearing a light overcoat, sweats, a pair of New Balance, and a gray T-shirt. His smile, like his coarse, straw-colored hair, is boyish. His heavy-lidded, hooded eyes -- at times he almost looks Filipino, or maybe Native American -- keep time with the tall man's talking by alternately slitting and getting big behind his tinted glasses. He's dignified disheveled at 60. He's smoking a cigarette, which he knows he shouldn't be doing. He introduces me to the taller man.

"This is Sims Lucky," Barry Hannah says. "He's a friend of Hunter's."

Lucky is telling Hannah a two-year-old story about Hunter Thompson shooting his secretary in the woods. The secretary was wearing a bear pelt, and so the incident was ruled an accident.

"You can't play a joke like that on Hunter," Hannah croaks out, laughing. "You can't dress up like a bear. He's nervous. This secretary, Sims, this personal assistant, was it a woman or a man?"

Lucky looks at Hannah like he's a savage on a newly discovered island. He looks bemused, impatient, willing to help.

"Barry, what do you think?"

"A woman. Yeah. Right."

Women.

Yeah. Right.

Hannah says "yeah right" in a different way than the rest of us do, and he says it all of the time, like the rest of us might say "you know" or "got it" or "OK," or like Cagney would say "see." It begins and ends a significant percentage of his sentences. "Yeah" is pronounced in a throaty clip and gets higher at the end, almost yeuh-aah. There's a short rest before "right," but it's not meant to express skepticism. Right's like a lid: Once he says it, the point has been made. You can make a counterpoint between yeah and right, you can elaborate, but not after the i expands slightly and the t pops it shut. Yeuh-aah. Reyet. Maybe it comes from his father. Maybe it's a Southern thing.

His fiction is definitely a Southern thing. His "creations," as he calls them, come from where he comes from, which is originally Clinton, Miss., in between Jackson and Vicksburg, and then Arkansas -- where he earned his MFA in creative writing -- and Clemson and Alabama, where he has taught (in addition to stints at Middlebury College in Vermont, the Iowa Workshop, and the University of Montana-Missoula). He now teaches at the University of Mississippi, Ole Miss in Oxford, where he has been writer-in-residence since 1983. He has taught Donna Tartt and Brad Watson, and taught alongside his "kindred spirit," Willie Morris.

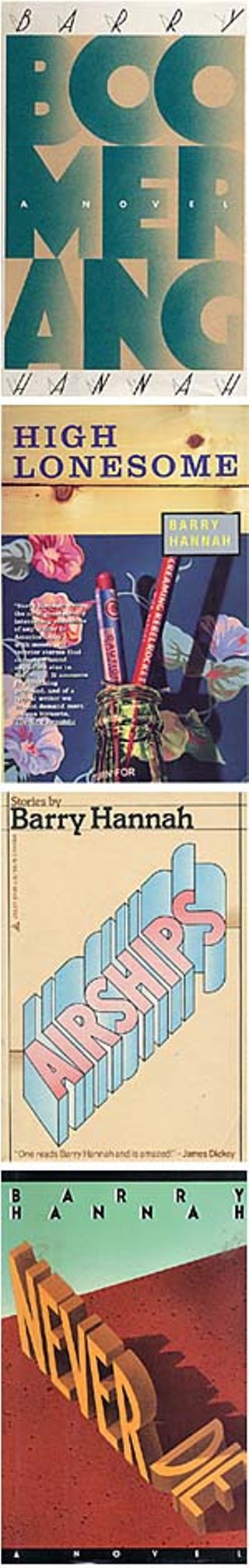

His novels, of which there are eight, and his short stories, of which there are four collections, ache with a marvelously elliptical Jack London-like autobiography, more so than most anyone else alive's. They are filled with lonely people, dangerous people, people lost among the lakes and vulgar territorial beauty of the American South. These people can be dismal and young, wickedly liberated, wretched, animalistic, aged. In tune with pure melodies or sickly ones. Civil War veterans or Desert Storm veterans, alcoholic musicians or serial killers. They can be so in love or they can be so mournfully far from loving anyone, least of all themselves, that the regret coursing through the author's lyrically electric sentences is often overwhelming.

Then again, he's considered by many -- including Robert Altman, with whom Hannah lived and worked briefly in 1980 after the success of his short novel Ray -- to be a comic writer, a joyful, optimistic one. In her Barry Hannah: Postmodern Romantic (LSU Press, 1998), Ruth D. Weston writes that "Hannah is having more fun than anyone with his writing, although his enjoyment must be as double-edged as are some of the tragicomic episodes he relates. ... Hannah's stories ... the Western and war fiction in particular, read more like Chaplinesque rewrites of the surrealities of Stephen Crane or Ambrose Bierce." In short, Hannah's work is a kind of realist escapism, funny but sad as all fuck out. This is maybe what makes him a "truthteller," as Weston calls him, whose prose is a kind of mirror -- a postmodernist mirror, yes, but a reflective one nonetheless. This is maybe what makes him a master.

112W Bondurant Hall, University of Mississippi

"The first thing I know about you, whore trader that used to be Fabian. Books are a very mortal sin. Books are not wrote by the Christly. I got no idea why a writer of a book should have respect. Or even get the time of day, unless he's a prophet. It's a sign of our present-day hell. Books, think about it, the writer of a book does envy, sloth, gluttony, lust, larceny, greed or what? Oh, vanity. He don't miss a single one of them. He is a Peeping Tom, an onanist, a busybody, and he's faking humility every one of God's minutes." -- Yonder Stands Your Orphan, 2001

Oxford, and by magnetic extension the Magnolia State itself, has a heavy, brilliant air about it. You can breathe it. Faulkner and his Yoknapatawpha County. Welty. Larry Brown. Richard Wright. Morris. Tartt. Thomas Harris. Ellen Gilchrist. Jim Harrison. Richard Ford. Even Fat Possum Records -- which, with the likes of R.L. Burnside and Cedell Davis on its label, fills its own literary niche -- is here. Thacker Mountain Radio can bring together the North Mississippi Allstars or Victoria Williams with Richard Flanagan or William Gay on a given Thursday night. The lion of American independent bookstores, Square Books, helps make that happen. Not to mention The Oxford American, the "Southern Magazine of Good Writing," which, after a decade of publishing everyone from Hannah to Guy Davenport to Cynthia Shearer in this tiny college town, was bought out in 2002 by At Home Media Group Inc. and gently shoved up to Little Rock. Bought out from John Grisham, that is, perhaps Oxford's most well-known (former) resident, and one who not only bankrolled the magazine until its near collapse, but who also funds a faculty slot at the university.

The day before finding Hannah out on the square for lunch, I'm waiting to meet him in the halls of the Ole Miss humanities building, Bondurant Hall. After he shuffles in with a cigarette and a Sobe "Adrenaline Rush" drink (which he seems to consume by the carton and case, respectively), we walk up to his office, which is just a few yards away from a door bearing Grisham's name. Hannah is a warm person, a man who makes you feel welcome without trying to. Behind his chair is a framed Miles Davis poster resting against the wall -- Hannah is a trumpet player who for a time played in the Jackson Symphony Orchestra -- while the décor is otherwise limited to a few photos, some books, and a stack of CDs alongside a small stereo.

We talk about Austin, specifically Hannah's adolescence-era friend and trailblazing University of Texas professor Horace Newcomb, who has made cameos in the author's output, and Newcomb's son, the guitarist Scrappy Jud Newcomb. With this writer's work and conversation, the subject frequently finds it way around to "pals" and music, and it's attractive, to be honest.

"People in Oxford think they're cosmopolitan, often, 'cause we really don't have a city here. But at Cash's concert in Austin [during SXSW 94, part of a story Hannah wrote for Spin], this 6-foot-2, skinny, black transvestite was screaming to get into Eno's. Emilio's? Emo's. And Emo's had 200 folks in it, OK? Yeah. Right. Imagine a black transvestite hitting the security guard in the head with her handbag, his handbag, to see Johnny Cash, the manly man. And I said, shit, we ain't cosmopolitan. This is cosmopolitan!" Hannah remembers, stretching. He rises suddenly, telling me that it's time for class. "He was highly indignant, if not broken-hearted. I knew I was still a country boy."

There are about 15 students in Hannah's graduate-level creative writing workshop, and most of them seem to be twentysomething, though a few are older. There is a couple in their 70s: Howard (who bears a resemblance to the late caricaturist Al Hirschfeld) and Sylvia, and they huddle up in the back corner. They are auditing the class and are graciously ceding the semicircle its space. Hannah squints at the gathering as if not recognizing them, but it turns out that he knows almost everyone by name. He begins passing out manuscripts. He takes a hit off of his inhaler. He winces. He sits down and crosses his legs, kicking up a tan suede boot.

After an hour of discussing a couple of stories that he is not particularly impressed with but fair to all the same, he is up at the chalkboard. He writes slowly, gently, and with great pause, much like he speaks.

"Nouns and verbs," he cursives. "HARD, good. Anglo/Saxon. Adverbs weakest part of speech. Adjectives -- Surgically precise." He crosses out "Surgically." "Not needed, right? Yeah," he says. "Right." He scribbles something else. "Know The Story. Beg. > Mid > End."

A student named Neal, who is in possession of an impressive beard, nudges me and whispers, "He writes this on the board every class." He nods solemnly.

The next morning -- after the phone rings and all I hear amid the motel construction is "Did you party last night? I would have. Let's meet at 12:30, if you got rest, if you're ready" -- I ask Hannah if they know who's teaching them.

"Oxford is basically a literary town, but I teach people who've never heard of me," he says. "Now, it's become more usual since we have a master of fine arts program. Four or five of those people you were in there with are studying for [an MFA], and yes, they know my stuff, and they came here for it, to study with me. I've taught both ways. It doesn't matter to me. I don't care. I just want their work out there on the sheets, typewritten. They know I'm not some assistant professor who's struggling to publish. And I'm not there as some genius, who thinks he knows what to tell these kids other than how to write their best stuff. I'm there to help them, and to get the paycheck. Nothing more.

"You get somewhere with the good students: They improve, and sometimes it's a quantum leap. They are some distance from someone like Donna [Tartt], who just simply broke the bank [with her 1992 debut, The Secret History], but to know that these gals and guys are gonna write something that pleases folks gives me some pleasure."

What do you think of writing programs in general?

"There are too many, but there's nothing wrong with too many schools having MFAs, and Texas is one of them. Texas is made out of millionaires, and one of the millionaires who has helped their writing was Michener. They have these fantastic scholarships, right? And Southwest Texas State is great, too. Yeah. Right. I have an MFA, and I needed it. I was young when I got in, and I could write, but I had nothing to say. ... I was ashamed of being from Mississippi, and this was the Sixties in Mississippi, when all of those Klan assholes were shooting blacks. The three civil rights workers were killed, and Martin Luther King in '68 just north of us in Memphis. I would much rather tell someone I was from Dallas, and I certainly did. But I got over it. ... To win the battle in Mississippi against just, uh, pure dumbness, is something. ... I didn't about know who I was till I was a graduate student."

Later, he is waiting to deposit his check at the First National Bank of Oxford after lunch at the Old Venice Pizza Co. on the square, and no one will come to the window.

"Nah, that's not her," he grunts when pointed to someone walking his way. "It's usually a black chick."

They're open, right?

"Sure," Hannah says. "It's only two o'clock. Geez. All I need is a pen and for somebody to pay attention to me."

Story of your life, huh?

He laughs. "Hey. Yeah. Right. Exactly. Show and tell. Like in the third grade. It's amazing how similar it is. ... It would be a hard time right now for me to live anonymously. You wanna get noticed by somebody, frankly."

I look at him for a moment, in profile, as he signs his check. This is the man that Larry McMurtry called "the best fiction writer in the South since Flannery O'Connor," whom Sven Birkerts said "writes the most consistently interesting sentences of any writer in America today." And Philip Roth, upon Airships' release so long ago: "Hannah is more than just a brilliant new voice -- he is a half dozen brilliant new voices." Roth knew. The critics know. The mainstream -- and even a few of literary fiction's dwindling devotees -- most certainly does not.

You're noticed. You've sold some books. Does it weigh on you that you haven't had a breakout book, though? Is it something you think about while writing?

"Yeah, it is. Why not? Why wouldn't I want to break out? Especially at my age. I mean, it's even, people need money! I've got all the critical respect I can eat with. I don't need it. I'm not even conscious of that that much anymore. The only reason that they've put me in the high-brow is because American fiction is so damn low-brow! American fiction is having a tough time right now, is it not? Personally, I'm tiring of what white men in this country have to say. I would love to have a breakout book, but it may not be in the cards. I haven't even had a movie, and several of my pals have. I would like a wide audience. My last book [Yonder Stands Your Orphan, Grove Press; see the Chronicle's review at austinchronicle.com/issues/dispatch/2001-08-17/books_readings.html ] was actually in airports, the first book I ever had in airports. I guess it's not the sort of book you'd find in airports, but I was really happy to hear that. My publisher, Grove, is just so good now, you know? Always has been. They've got that underground thing, but they can also sell. I think that book sold the most of any I've had.

"I'm grateful to sell 20,000 books, man. I was shocked, however, when I was your age, and I was about a year older when my first novel [Geronimo Rex] came out, that I didn't sell 100,000 copies. I sold 5,000. It was nominated for the National Book Award, for God's sake, and I thought this meant something. I was wrong. I just didn't know publishing."

Eagle Springs Road

Then I went back to the bathroom mirror. The same hopeful man with the sardonic grin was there, the same religious eyes and sensual mouth, sweetened up by the sharp suit and soft violet collar. I could see no diminution of my previous good graces. ... my vocation was interesting and perhaps even important. I generally tolerated everybody -- no worms sought vent from my heart that I knew of. My wife and other women had said that I had an unsettling charm.

-- "Our Secret Home," Airships, 1970

The phone rings in Hannah's home office, a small wing unto itself in a green-and-white ranch-style house just minutes from the courthouse square. There is a motorcycle in the driveway, covered up. I glance around as he sits quietly with the receiver cradled to his ear. The room is spilling over in colorful shelves full of books, though the author has recently donated 150 volumes to the library. The .22 rifles he collects -- "I don't even hunt, I just sometimes shoot beer cans for sport" -- lean up overlapping spines. There are photographs everywhere, maps, murals, documents, some awards. His third wife, Susan, walks in. They have been together for 17 years. She has been interrupted while watching The Bishop's Wife. She is petite, with short blond hair going a little gray and blue eyes so impatient with a need for action that you feel honored if they stay on your face for more than a second. Their six dogs are barking like crazy. She is smoking. She is sipping from a giant jug of what must be iced tea.

"Excuse me," she says sweetly, looking at her husband. "Do you have an appointment with Dr. Stewart tomorrow?"

"I can't remember. Why?"

"Well, they just called and said that I had an appointment for tomorrow."

"Yeah. Right. They asked for you on the phone. Uh-uh. I don't have an appointment period with Dr. Stewart."

"OK. Just checking."

"Have you ever been to him?" Hannah asks.

"Dr. Stewart?"

"Yeah."

"Yes," Susan says. "But they had me down to go in and have my asthma checked."

"You don't have asthma."

Austin Chronicle: You talked earlier about readjusting your mortality in the wake of recent events, like your lymphoma and even the shuttle Columbia. How does that affect your work?

Barry Hannah: I remember when I was your age, you're always going off to someone's wedding. For me, now, it's funerals. A good buddy who was only 51, and a cousin who was 58. So, I've had a big dose of close mortality lately, and it doesn't make me anxious to produce, but it just -- here I sit with a cigarette in my hand -- it reminds you of just how precious minutes are. You better be nice to folks and get your stuff done. Just cut the shit, you know? Cut the shit.

I'm doing too much schoolwork with the MFA stuff. It keeps biting at your time. I've got three books with notes and scenes. I'm just hoping that one fine day, as it will for a lot of other folks, this stuff's gonna gather, it's just gonna gather, and it's gonna have impetus, and it's gonna start writing itself. I mean, this is the way my novel is starting, so, you know, it's going somewhere, I just don't know where. It's called Last Days. I'll read you some now, not a lot, but enough ... which I've never done for any interviewer anywhere, ever. [Reads from Smith Corona-typeset pages, though he begins everything in pencil, which means this is probably serious; finishes after a few pages] I'm kind of impatient, because this book is lagging on me. But I like the way that moved all right. I wanna stay with that. ... One thing about getting older, I wonder if there will ever come a time when you are quite content to have only your memories. And to disassociate all belongings, all poetry, all everything, from yourself. I wonder if you ever get there.

AC: Maybe at the very last second. You've said before that people in the South are nostalgic by the age of 11, and yours seems almost a literature of regret, I think.

BH: If it's there, it's there. I don't go around thinking about regret; regret doesn't consume me as a person. ... I'm not certain about whether any writer, any artist, any musician, can write without regret, so I don't think perhaps it's even particularly Southern. But, even so, you kind of reconstruct and make it different when you write. Regret and nostalgia would make up a large part of the motive for creativity, even if it's from two weeks ago, you know? Yeah. Right. ... I regret being unkind when I was drinking, especially to my children. That's the biggest thing. The lost months, years, when I was a heavy drinker. I was writing, but I sure wasn't there for anybody much.

AC: Can we talk about that?

BH: I had a whole different physiology. I mean, I got cranked up at seven drinks. I was just establishing my thirst. ... It was a heavenly gift. I would never want anybody to mimic this, and actually, they can't, some of them. You either can drink a lot and work, like I did, or you can't. And for other people whose genius far surpasses mine, two drinks put them to sleep. They have never associated alcohol with composition itself. Even [Raymond] Carver, who was alcoholic, said he never wrote a story on the bottle. I guess I asked him up at Syracuse, "Were you ever hung over [when you wrote]?" And he said "Sometimes, a little."

Disinhibition is what we're talking about, creatively, for me. I just wasn't afraid of anything much in my better drinking times. At the end, it's always you're too sick to write and you're not producing, though you lie to yourself. I was very deeply frightened that if I quit I couldn't write at all. ... It seems to me I go back to a book that was written in the Seventies, Airships, during which I was loaded -- most of the time I was knocked-out loaded -- and those stories go over hugely with audiences. ... I fear that it could be I wrote best in the Seventies, as I was a minor alcoholic, not yet a major. I might have had some touches then. ... I've changed greatly. You don't want to be a has-been. That book High Lonesome [which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 1996] was totally sober. I haven't had a drink in, what, 13 years? Bats Out of Hell [Susan's favorite] was totally sober.

But this waiting period for a novel is not any fun. None. I'll threaten to drink here. I'm not going to do it, but do you understand the temptation? ... I'm personally so concerned that I'm not pleasing myself with my stuff as we speak. But that's -- for good or bad -- where your head is. Your next creation. And you have fears that you've said what you wanted to, and that it's over. And sometimes you have to wait quite a bit for something new to come along, which is very harrying and wearing.

AC: Did you ever think that Yonder Stands Your Orphan [2001] would be your last book?

BH: I had, three years ago, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, as you know, but I was never frightened of the cancer. I almost died of, uh, pneumonia, because of low immunity. And so that book was written a good ways already, but I finished it actually on steroids, they were my only energy. I wasn't really thinking last, I just had pretty much confidence that I was gonna get by this. But you never know, baby, you know? I've made 12 books. I don't believe I'd be ashamed if that were my last. But I wouldn't be happy had I only been a teacher, if all I had done was help young people, frankly. I don't get nearly the joy teaching as I do out of creation.

But when Stephen King was here, I was on this panel between King and Grisham, who were at that time the bestselling writers in the world, what, five, seven years ago? And, uh, King was just talking about the joy that he even started writing on Sundays, that he just couldn't miss the joy of creation, and I must admit that the joy has receded from me somewhat. It's more deliberate at times, but when I get into it, the joy comes back.

That chemo, man, that just knocks the hell out of your system. It's carpet bombing. You come out a skeleton if you're lucky. And these drugs, I'm taking a lot of drugs for maintenance, and some of them are anti-depressants. And I'm not a depressive person, but after three years of ailments, my body got depressed. ... So, I'm not at my favorite spot right now. ... But I go to the gym. I'm in pretty decent shape. You know, maybe indeed my body will have adjusted, and some of these drugs will be withdrawn. You can teach on drugs, you can write essays on drugs. But these are drugs that no creative person would want to take. They take away the unconscious, and the unconscious is where it's at. And the joy. Where the stories write themselves, spiritually. I haven't been there, spiritually, for quite a while. Quite a while. But there's also the possibility that as you age you write some better sentences. They're informed with a different kind of fire than when you were young, but they're good, still.

Honestly, I envy painters, who can have a masterpiece in one morning. Or musicians, who can write something in 30 minutes and arrange it in an hour, sometimes. 'Cause with this, with writing, you can occasionally feel like a caveman, like you've been working with pitch and tar on this brush. I guess the drudgery of the medium gets to you after a while.

Rowan Oak

"Fuck Faulkner's shadow."

-- Barry Hannah, Feb. 5, 2003

It's getting cold and dark gray outside in Oxford. The noise that our shoes make crunching against the long gravel trail, slow and steady under rows of wintry oaks, is a welcome reminder of what exactly is going on here. Barry Hannah and I are walking to William Faulkner's house. "We're close, we're getting closer to the great genius," Hannah laughs. "We're not far now." And then he's quiet for a while. I start to speak, but he interrupts. "You know, I stopped reading him when I was around your age, my mid-20s, and stayed away from him a long time. Faulkner's about as good as it got. He might be the last word, you know?"

One of Faulkner's several anointed Southern heirs, the 60-year-old surveys what he calls the "best-looking property in town, the best piece of real estate, and it looks a hell of a lot better now than when he was living in it."

He looks at me. "I'm doing this because you didn't ask me the same dumb question that everybody asks me, thank God ... 'What's it like writing in Faulkner's shadow?' Well, fuck it, fuck Faulkner's shadow. It's not a shadow, anyway, it's a goddamned ghost. And it's a good town for that ghost. He scared me when I was younger, maybe, but not anymore."

What scares you now?

"Frankly? Losing out on women buying my books, and reading me, because of the violence." He smiles, and the grooves in his face get deeper. "The market, let us say, has gotten more female."

The violence in your work, or the accusations of misogyny thrown at your work. Or race. This isn't the first time it has come up in a interview for you.

"No, it's not."

Is that all part of the escapism? The truthtelling?

"I don't know. I couldn't know that. I don't think the writer should be the final judge on what he is, anyway. Who knows?" Hannah sighs. "But I'm not going to beg off. I can't convince somebody of the opposite of what they read. I would never try to do that. ... I have been gentler toward women in my fiction in the last several years. I've been more alert to women as whole souls. The earlier fiction was just sexy stuff. I'll tell you what, though, I can't promise anybody that I won't get into violence. Sometimes it's the only thing I can think of that will bring off something true. Like Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, or Bukowski's poetry. The exciting American stuff. The European modernist stuff, like Kafka. It would be a shame if it were always the only thing I could ever think of, but it's not. I probably get off on it, somewhat. I think I do. There's a part of violence that's almost like vaudeville. Just seeing somebody knocked to all hell is funny onstage. But you know what? I get squeamish, or just kind of nervous, with fairly graphic sex scenes or gratuitous violence on screen, so it probably sounds like I'm a hypocrite.

"But we played violent when I was small. We'd build a whole village, and spend a day doing it, and then the next day shoot matches into it and burn it down. And this was an art! So, in part, similarly, I think that writers do use destruction as an art. A writer's job is to destroy, and then to build the thing back up again by a chosen means." ![]()