Born to be Reviled

Easing on down the road will be tough for TxDOT's I-35 expansion plan

By Dave Mann, Fri., Sept. 20, 2002

Given the controversy surrounding the plan to expand and revamp Interstate 35 through downtown Austin, you'd think the project schematics would be sealed in some subterranean government vault, protected with mighty steel doors and sensitive security systems -- something akin to the Bat Cave. Instead, they're found in a squat Texas Dept. of Transportation office building, stacked with dozens of other rolled-up highway sketches in a tiny space that resembles a high school art classroom.

Charles Davidson, the chief project engineer, spreads out the expansion plan on a long table. He looks like you'd hope a highway engineer would: not geeky and distant, but large, affable, and khaki-clad, with pale skin, perfectly parted hair, and a cozy Southern accent. A graduate of the University of Tennessee, Davidson came to TxDOT three and a half years ago and has been project chief for about a year (the I-35 plan has gone through two previous project heads). "So they can't say I'm some Aggie trying to mess with [the University of] Texas," he says, smoothing out the highway design.

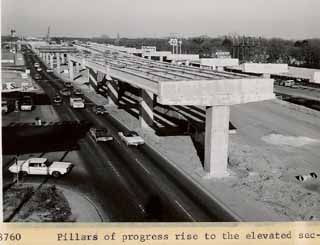

On paper the expansion doesn't look all that impressive, but make no mistake -- it's a behemoth project. In its current incarnation, the plan would affect a 45-mile stretch of I-35 from Georgetown to Buda, revamping poorly designed sections and adding two all-purpose lanes and two elevated HOV lanes to the downtown stretch. This would require roughly $2 billion and 10 years of construction, resulting in untold effects on Eastside neighborhoods and bedeviling traffic; if you think the highway's crowded now, just wait until they build this thing. With so much at stake, controversy has become a major part of the planning process. As if on cue, a coalition of Eastside neighborhoods has banded together to fight TxDOT's current design.

In his office, Davidson glances over the schematic and points to one Eastside neighborhood after another, each time remarking, "They hate me, and they hate me, and they hate me too." He places his palm over the area marked for the Wilshire Wood/Delwood I neighborhood: "And they really hate me." Based on the design and TxDOT's past transgressions, residents in these areas believe they'll bear the brunt of construction. Consequently, many have joined the North Central I-35 Neighborhoods Coalition (or NCINC; in case you're wondering, it's pronounced "in sync"), which formed last year. The coalition has a smorgasbord of complaints about the current design and has asked area planners and TxDOT to commission an independent review of the plan before seeking the required federal approval next year.

NCINC's concerns range from minute disputes over design and placement of exit ramps to larger questions about the rationale behind the entire project. Everyone agrees I-35 must be improved: With Austin's projected population growth in the next 20 years, TxDOT estimates it will take 18 lanes to satisfy traffic demands on I-35 by 2025. Yet that figure alone makes neighborhood leaders wonder if the current plan is worth it. Why pour so much time, money, and effort into building a 12-lane highway that, without other alternatives, will be outdated the day it opens (scheduled for 2020) in the face of 18-lane volume?

Area planners concede the I-35 expansion is a mere drop in the transportation bucket, its success dependent on construction of commuter and light rail, the State Highway 130 bypass, and HOV lanes on MoPac. Without these, Davidson freely admits, the new and improved I-35 will be a $2 billion parking lot from the start. Asked whether these alternatives, on which his plan is so dependent, will actually come to pass, Davidson shrugs and offers, "Your guess is as good as mine."

It's that uncertainty, combined with TxDOT's poor community relations, that raises neighborhood leaders' skepticism as TxDOT plunges ahead with plans to rebuild Austin's most vital roadway.

A Growing City Must Grow Its Highways

Everywhere you turn in the Austin area these days, TxDOT is planning and laying down new ribbons of asphalt in an effort to keep the area's transportation network on pace with its burdening population growth. There's SH 130 to the east, perhaps ready for construction next year; SH 45 to the north, already under construction, and its planned southern component; the web-like I-35 interchange with U.S. 290 and SH 71; the U.S.183 expansion, trickling along in its 20th year; even the governor's fantastical Trans Texas Corridor idea. But the I-35 project is the lumbering granddaddy of them all.

The I-35 Major Investment Study (MIS), as it's lovingly and appropriately known in official circles, has been with us in some form since the mid-1980s. TxDOT first commissioned a study to examine expanding I-35 in 1987. After changes in federal law, TxDOT placed more emphasis on building HOV lanes along the highway, and in 1991 organized the I-35 Interagency Development Team, made up of local stakeholders: the Federal Highway Administration, Austin Public Works and Transportation Department, Austin Planning Department, Capital Metro, Texas Transportation Institution, and of course, TxDOT. For the past 11 years, the project has creaked through the bureaucratic mesh of staff meetings, feasibility studies, public hearings, and redesigns. In recent years, transportation planners have pushed ahead with the first phase of the I-35 MIS, considered myriad designs, and are now ready for Phase II. The design options have been winnowed to three: Do nothing to I-35, build HOV lanes only, or add two main lanes and HOV lanes, along with safety improvements. That final option is the one favored by most transportation officials and is the most likely choice.

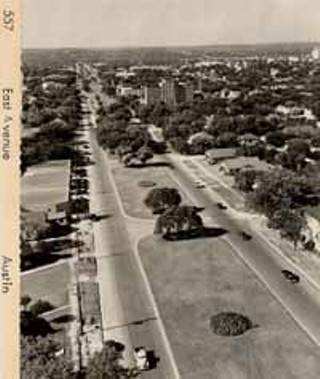

All the while, Austin has grown, and so has the need for an I-35 upgrade. The highway was completed through Austin in May 1962, its upper deck through downtown finished in 1975. The highway quickly became a key artery, stretching nearly 1,600 miles from Duluth, Minn., to Laredo and, along the way, passing through such metropolitan centers as Dallas-Fort Worth, Oklahoma City, Kansas City, and Minneapolis. Austin's section is one of the highway's busiest: According to a recent government survey, more than 25% of residents in the metro area use I-35 for daily commuting. Each day, more than 200,000 cars and trucks cross Town Lake on I-35, making that road the busiest six-lane highway in Texas. By 2020, TxDOT consultants predict, 330,000 cars and trucks will cross Town Lake each day -- the transportation equivalent of trying to shove the Colorado River through a garden hose.

That traffic load and a series of poorly designed spots also make Austin's stretch of I-35 the highway's most dangerous. Between January 1991 and December 2000, 277 people died in auto accidents on I-35 in Travis, Hays, and Williamson counties, according to the Texas Dept. of Public Safety. By comparison, Dallas County suffered just 199 fatalities on I-35 during the same 10 years.

The need to somehow relieve the traffic burden on I-35 and improve safety is clear to all parties involved in the debate. The lingering question: What's the best way to do it? Charged with resolving that quandary is the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO), a board of area leaders -- including City Council Members Daryl Slusher and Will Wynn, and chaired by state Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos -- that forms elaborate transportation plans based on the area's future needs, and coordinates with TxDOT and Capital Metro to implement them. According to its latest 25-year plan for the city, CAMPO seeks HOV lanes on MoPac, an expanded U.S. 183, commuter rail along the Union Pacific tracks beside MoPac, and an east-west light rail network, in addition to the new and improved I-35.

When Wynn became involved in the I-35 project in 1995 as a developer and member of the Downtown Austin Alliance transportation committee, TxDOT was still stuck in "pave the planet" mode and planning to double-deck Austin's section of the highway. That design was a monstrosity, he says, with eight lanes on each deck and arch-like exit ramps that looped over the second deck and sliced through six city blocks before descending to street level. The scale model of the design was "disastrous looking. When thinking people saw it, they wanted to laugh," Wynn says. Through the DAA, Wynn and others helped TxDOT create a less disruptive design featuring fewer lanes and a recessed main roadway so that surface streets could reconnect, bridging the barrier between east and west Austin. "It didn't go over well with TxDOT, but they came around," Wynn says. Eventually, the recessed-roadway plan became the basis for a scaled-down design that adds just two main lanes and relies on HOV lanes.

Yet those changes haven't pacified many Eastside neighborhood associations, which already distrust all things TxDOT and now are being asked to swallow a $2 billion road project that could, on its own, accomplish little, while wreaking havoc on their neighborhoods.

'Show Me the Cocktail Napkin'

Last fall, after disheartening meetings with TxDOT, leaders from the Cherrywood, Blackland, Wilshire Wood/Delwood I, and Delwood II neighborhood associations formed the North Central I-35 Neighborhoods Coalition to lobby TxDOT concerning their complaints about the project. Thus far, these North and Central Eastside neighborhoods have been the most vocal in criticizing the I-35 design and were the first to challenge the reasoning behind the current plan. But nearly all Eastside neighborhoods north of Town Lake have concerns. The Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Association, for example, frets that the reworked Cesar Chavez exit ramp will harm the surrounding area and pour more traffic through the neighborhood. Though started in the north, NCINC hopes to push the Eastside's common criticisms concerning traffic volume, exit placement, noise and air pollution, and cost. In the past few months, seven additional neighborhood associations have signed on, including East Cesar Chavez, Hancock, and Holy Cross; Just Transportation Alliances and Austin Neighborhood Council also have expressed support for NCINC. "Our concerns are not limited to a specific location," says Cherrywood NA member and NCINC Chair Stefan Schuster. "There are negative impacts on neighborhoods all along this highway."

On a rainy night late last April, Eastside residents and other interested parties trickled into the LBJ Library's red-seated auditorium to hear TxDOT officials unveil their latest design for I-35. It was the first of three public meetings last spring, after which TxDOT would review citizen input and begin composing the design to submit for federal approval and funding. The new design featured a few changes, but the basics remained the same: a depressed main roadway (except at Airport Boulevard and select intersections), with two HOV lanes elevated to the height of the current second deck.

Building a highway through dense urban areas has always been a tricky business, not only in terms of engineering, but also in convincing residents to support a bigger road barging through their neighborhood. In the golden oldie days of highway construction, engineers could usually kick away half a neighborhood and slap down as many lanes as they wanted; for instance, whole communities were ruptured when New York built the Cross-Bronx and Brooklyn-Queens expressways. Nowadays highway construction is exceedingly complex, given intricate funding-approval processes, detailed environmental assessments, and public meetings to gain citizen input and support. For projects as extensive as the I-35 Major Investment Study, public cooperation is especially important: Well-organized resident movements have fought and killed bloated highway improvements across the country. TxDOT's Davidson calls Austin the toughest place in Texas to build a road, due to its entrenched mindset of civic activism.

Take, for instance, that April meeting at LBJ. TxDOT officials not only had to inform residents of the new design, they had to sell it. During the public comment period, however, it became clear that most residents still weren't buying. Many Eastside residents told TxDOT officials the project would bring too much traffic through their neighborhoods, spew too much air pollution, and make too much noise. Furthermore, they wondered why the HOV lanes were elevated (and why they spanned only from 51st Street to MLK Boulevard), and worried about the possible expansion of Manor Road -- which TxDOT calls "a city government issue" -- and the lack of direct access to the Mueller Airport site.

Other speakers challenged the entire expansion concept. Retired state employee Bo McCarver, an Eastside activist and member of the Blackland Neighborhood Association, berated the plan as a continuation of the "rubber-tire policy," and criticized TxDOT for not considering light rail. When McCarver finished, John Hurt, TxDOT's public information officer and moderator for the comment period, said curtly from the podium that TxDOT doesn't build rail. "Well you ought to," McCarver shot back from his seat, inciting a flare of applause.

Afterward, McCarver echoed many people's sentiments when he labeled the meeting a "waste of time." Not long after that meeting, NCINC submitted a position paper to TxDOT as public comment, detailing its complaints large and small about the design and requesting the agency and CAMPO to commission an independent engineering study of the plan. If it seems odd that residents are asking for another layer of bureaucracy and study, well, that only shows how skeptical NCINC is of TxDOT.

"By the time they're done [with the project], it [will be] outdated," says Schuster. "You're not going to decrease traffic congestion by building additional roads." He discusses Austin's transportation issues all the time with co-workers and friends, he says: "It doesn't take two minutes of conversation before people come up with what-ifs. 'Why don't they keep the upper deck for bikes? Why don't they have light rail?' The suggestions come so fast, you think, 'Well, why doesn't TxDOT come up with some of them?'"

Meanwhile, McCarver argues that if Austin continues down this path, it will end up with a transportation predicament much like that vexing Houston, where growth has outstripped local roadways. Houston is scurrying to belatedly build a light-rail system (without federal funds, by the way, thanks to legislation from U.S. Rep. Tom DeLay that forbids it) and is considering expanding the Katy Freeway to 20 lanes. "Austin is heading that way if we keep adding lanes of freeway," McCarver says, noting that one light rail line could account for six lanes of normal highway traffic. Perhaps some of the I-35 expansion money would be better spent on alternative means of transportation instead of adding two lanes that will be obsolete when opened, he posits.

McCarver worries that expansion could preclude any future rail line along I-35 by eating up all remaining right-of-way space. In some sections near UT, Concordia University, and Mount Calvary Cemetery, TxDOT will be out of usable land after this expansion. "If you had a north-south rail line along the highway on TxDOT right of way, that would really cut down on traffic," McCarver says. "I don't see where that was considered." For those who need reminding, Austin voters rejected a light-rail referendum two years ago, though planners are still hopeful for eventual passage.

Adds Schuster, "They think they're the Texas Department of Highways, and not the Department of Transportation." If TxDOT hasn't projected how much congestion rates might increase without light rail, expanding I-35 before rail and alternatives are available could amount to putting Austin's transportation chicken before its egg. "Show me the cocktail napkin where the calculations were made," he said.

Caution Signs Ahead

Michael Aulick, executive director of CAMPO, scoffs at McCarver's notion that the I-35 design is a continuation of the "rubber-tire policy." The expansion project is, in fact, a progressive plan, he argues. Adding just two lanes and two HOV lanes to I-35 is not a regression, not "your usual pave-the-planet plan," Aulick says, but rather makes use of alternative transportation means. In years past, he notes, TxDOT and CAMPO simply would have "double-decked" I-35 and refused considering alternative transportation. The key, he says, will be the HOV lanes, which could greatly reduce the volume along the main lanes, along with express bus service. "Expanding a highway in an urbanized area is hard and it's disruptive, and we're trying to balance people's needs," he said. "What we're looking at now is disruptive, but not nearly as bad as the old road warriors."

There is no panacea for Austin's transportation crunch, Aulick points out; the I-35 project alone can't solve the problem, nor is it supposed to. Instead, CAMPO's plan relies on what he terms the "five sisters": I-35 and MoPac expansion, light rail, commuter rail, and the SH 130 bypass. Most of those "alternatives" are not guaranteed, he admits -- especially the rail proposals -- yet planners should push ahead with the I-35 plan anyway. "It would really be good if, before we started tearing up I-35, we have some kind of rail," he says. "But if time comes to fund I-35 and we don't have light rail, we go ahead and do it. It's too urgent." Delaying the I-35 plan would be "very dangerous."

Still, the plan must pass through numerous bureaucratic hoops before it's even considered for funding. First, TxDOT must finish the environmental assessment, which it hopes to complete this winter (some think that's an overly ambitious timetable). All manner of agencies must comment on the design, including the Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept., the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Texas Historical Commission. For TxDOT, one treacherous element of the environmental assessment could be the historic-resource review; historical structures rim I-35 on the Eastside, and the agency could be forced to significantly alter its plans to avoid impacting these structures. A potential battle over historic buildings is one reason several sources believe the environmental assessment will take longer than six months.

Next spring, TxDOT plans to hold a public hearing to present its final design and environmental assessment to the public before submitting the plan for federal approval. After that approval, the agency can begin securing funding and trying to buy right-of-way land. Even if all goes well, construction won't start until 2010, Davidson says. In addition, CAMPO and the Austin City Council must approve the deal -- which isn't a sure thing, especially given the high level of opposition from nearby residents. Roland Gamble, the project coordinator for TxDOT's consulting firm, EarthTech, and a former TxDOT employee, refused to comment for this story, referring all questions to Davidson, as did TxDOT District Engineer Bill Garbade.

Schuster of NCINC says TxDOT will have a hard time winning over residents unless it improves its Politburo-style public input process, which he says is unresponsive to comments at best, smug and defensive at worst. Some local officials have acknowledged or echoed his concern. "My office receives complaints about TxDOT's public involvement process more frequently than I would like," Sen. Barrientos wrote to NCINC members in a June 11 letter responding to the organization's I-35 position paper. "Clearly, the quality of the public's experience should be as relevant as the number of opportunities." Barrientos sent a separate letter to TxDOT, asking the agency to respond in writing to NCINC's complaints. "I'm not angry with TxDOT," he said. "But I do pass on what my constituents are telling me, and I expect TxDOT to listen." Council Member Slusher, also a CAMPO member, agrees that TxDOT must improve its public involvement process. "People in Austin are taxpayers and deserve to have their say in what the highways look like," he said. "I'm not sure they're getting it right now."

Back at his sketch-covered desk, Davidson wonders what else he can do. He's met with various neighborhood groups more than 80 times, read thousands of public comments, issued newsletters, and maintained a project Web site. He's just an engineer designing a road, he says, incapable of undoing TxDOT's past transgressions. He and TxDOT officials say it's CAMPO's job to sell the plan -- they're simply designing the road they were asked to build. And yet, Davidson says, at several meetings people have screamed and cursed at him. "Every time there's a meeting, they print up these red flyers and tell everyone that TxDOT's going to come tear down your house," he said.

Schuster concedes he pities Davidson. "Charles shouldn't have to deal with someone like me," he says. "He's an engineer. They need a planner -- somebody who is the face of TxDOT, who just doesn't respond with a defensive remark. I've yet to meet that person." Hopefully, he says, TxDOT will one day soften its tone and share more information with residents. "We all want a better I-35 -- we just need to figure out a way to do it. Everyone needs to have information so we can move forward."

Botching a project of this size could leave lasting lesions on the area. As Davidson put it, "We're going to have to live with this for a long time." All the more reason for planners to take more time with this design and make sure they get it right, Schuster asserts.

"I think they're getting a lot of pressure," he said. "They're rushing something out the door because they need to solve the transportation problem. But let's not rush this. Let's look at this again before we spend all this money." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.