In Memoriam

Eagle Pennell, 1952-2002

Fri., Aug. 30, 2002

Eagle Pennell died a few weeks back, a talented, influential filmmaker who had become a hopeless alcoholic. His last film, Doc's Full Service, made in 1994, was full of promise. Unfortunately, it was the promise of a first-time effort from a novice filmmaker, not the final of five films by a then-mature talent.

Talented and influential: Eagle directed two films, The Whole Shootin' Match and Last Night at the Alamo, that stand as classics of regional filmmaking and influenced the generations of filmmakers who followed him. Robert Redford made it clear that one of the things that inspired him in establishing Sundance was seeing The Whole Shootin' Match.

A hopeless alcoholic: Eagle periodically showed up at Chronicle offices usually drunk (very rarely he was sober and on the wagon, though that never lasted long). More than once, having left one Houston rehab facility or another, he had gotten drunk on the plane and showed up to borrow money to pay the cab for delivering him to the Chronicle and then to the liquor store. I shouldn't have, but I always gave Eagle money. Whatever money he got, he spent immediately. Once he showed up with $500, gave me a hundred to pay off his many loans, and called a cab to take him to the Driskill to spend the night. He showed up a day later, drunk and broke.

Despite the stories of the last couple of decades of Eagle's misdeeds, there are these films and, fortunately, they speak even louder than he ranted at his worst. It is important to remember that though directors often get all the credit, independent films, especially, are invariably collaborative efforts. Eagle was able to realize those first two films by working with a large group of gifted and talented people. We asked some of them to offer their memories of Eagle Pennell, filmmaker. Here are their reminisces. -- Louis Black

But the Pictures Got Made

In 1974, just about the time I decided that I had to be an actor, somebody introduced me to Eagle Pennell. I had been around the then-really fledgling film business since I visited the set of that most unsung of all Austin-made movies, None But the Brave, in 1961, while I was on leave from the Army, so I thought I knew something about Austin film history. We talked film almost constantly. I told Eagle that, from what I had seen, a whole lot of people sat around talking about being filmmakers but didn't make any films. He bunked on my couch for about six months, and we started talking about making movies on whatever we could find to make them on. The first film we did was "Hell of a Note," and we shot it with unblimped (nonsilent) cameras with mic cables up our britches.

I could tell you about the time on "Hell of a Note" that Eagle told Tyson McLeod, Sonny Davis, and me to get in the truck cause we're going to shoot this scene of us driving down West First Street and Eagle had taken the hood off of the truck and had found a place sitting on the radiator with his feet hooked down in the engine so he could shoot the scene and not fall off the truck. No rope, no net. Or I could tell you about the time on The Whole Shootin' Match that Sonny and I did a long scene where we had this argument in a truck at night and somebody was outside swishing a light by us 'cause it was supposed to look like cars were going by, and we didn't have enough crew to have somebody wiggle the bumper so that it looked anything at all like we were actually driving, and we decided to try a take and when we were through, Eagle says "that was great, I've got it," and Sonny and I decided we were pretty hot stuff and started calling ourselves the One Take Kings, only to hear years later that that was all the film Eagle had that night. Or the day we were shooting the last scene in the movie and ran out of film and light at the same time up on the Devil's Backbone. It was foggy, and if we came back we couldn't match the light, so Eagle went to Austin to get more film, and all six of the cast and crew just stayed out there that night at a Boy Scout camp (and went to bed without any supper), and Eagle showed up (it was still foggy) at 5am with a bunch of 100-foot rolls of film, which last about two minutes each, which lead to massive cutaway shots. Or I could tell you about the time when we had to shut down shooting on Last Night at the Alamo so Eagle could go out to a West Texas cemetery to commune with his dead grandfather.

But the point is that the pictures got made.

I'll remember a guy who was as personally empowering as anybody I ever met. It may have been that the faith he had in me as an actor was just so that he could get the movies made, but I choose to think differently about that. In the first scene of one of these movies, Sonny and I did a take and Eagle said "that's great, I got it," and one of the crew said "hey, you guys can do better than that, can't you?" and Eagle almost killed the guy. I knew we didn't do it very well but what had been important was to get a shot in the can and move on. I think the scene went in the movie under music anyway, so you couldn't tell how bad we were.

I'll remember all these parts of Eagle, and myself, but I will also remember a guy who took the auteur theory too far to heart and decided that no one else had the talent that he had, a guy who mistook his talent for entitlement, who didn't realize that in this most collaborative of arts that he indeed had the right people at the right time around him and that those people were bringing their best stuff with them, that they did indeed come because he called, but that he didn't do everything and was nothing without them.

I know this last bit may seem to be a harsh assessment of our friend Eagle, but it is meant as a warning, not a reproach. Anyone who knows me will remember that Eagle and I shed blood, sweat, and laughter together, and that I wasn't perfect and neither was he. Or anybody else. I loved him like a brother, and I think he loved me, too. I've missed him for years.

As much of a Texan as Eagle tried to be, he forgot a basic Texas tenet: He didn't dance with who brung him.

You gotta dance with who brung you. -- Lou Perryman, actor, The Whole Shootin' Match, Last Night at the Alamo

A Long, Tall Drink of Water

It was 1978, and I was sitting with Billie Lee Brammer in the Soap Creek Saloon on Bee Caves Road listening to Delbert McClinton (three bucks admission). Up walks a long, tall drink of water who says, "Lin Sutherland? You're a writer right?" Well, I was very much of a new, young writer, but I was willing to acknowledge the possibility. And that right there expressed something about the man, Eagle Pennell -- he had a way of making people stretch. I was 28, Eagle was 25 years old. He was Glenn Pinnell from College Station, but as a filmmaker he became Eagle. My first impression was that he was a very directed, very take-charge young man. He told me he had finished a short called "Hell of a Note" about two Texas buddies. When he told me about it, the characters intrigued me and seemed Texas-real instead of the usual cardboard characters Hollywood fabricated with Texans. It appealed to my seventh-generation Texas blood. He wanted to do a feature using the characters in "Hell of a Note" as a springboard. Would I help him write it? I replied I had never written a screenplay. He said "Hell, it's easy. Go read Stagecoach and you'll see how it's done." Well, I did that. I went to the library and found about four screenplays, but one of them was Stagecoach. INT, EXT, it said. Eagle and I met again and he started talking the story. I started adding to it and started writing. That's how The Whole Shootin' Match was written in about three months. We met, we talked, we wrote. Then it was finished, and I was proud of this script -- it was genuine. "Now we've got to raise the money to shoot it," Eagle pointed out, and so off we went, pounding on friends' and acquaintances' and kinfolk's doors to ask for contributions. I even got my sister Kay to contribute $250 (a lot back then!). We were filled with the belief of our mission, and Eagle with a passion to film his vision. We raised about $45,000 and filmed a two-hour black and white movie on that. We each did many jobs of course, and worked long hours. It was a blast. We were filming by the seat of our pants; I was learning every day. I watched Sonny and Doris and Lou do something I'd never witnessed before -- take the written words of the script and make it come alive with fabulous original energy and expression. They were the characters. Eagle was intense and driven and high on the power a director has. It was a prelude to his being high on a hell of a lot else, but I didn't quite cop to that then. At the end of shooting, all of us exhausted, Eagle went into the editing room. The film was sent right out to the USA Film Festival in Dallas, where it was noticed, and then to the Sundance Institute in Utah, in the first years of its film festival. I remember well the quote from Robert Redford when he saw it -- in print he said The Whole Shootin' Match was "a prime example of what we're trying to do with independent filmmakers -- quality stories out of the Hollywood mainstream." It made me proud. The two years after, the film won seven awards in film festivals and went into distribution to small art film houses. We were able to pay back our investors. Eagle's direction, in both senses of the word, made it possible for a lot of lives to veer onto a new and interesting course. His own -- so full of originality, talent, and vision -- he sent hurdling toward destruction. The group that made The Whole Shootin' Match experienced something precious and unique. Eagle couldn't have done it without us, and we couldn't have done it without him. The Whole Shootin' Match was the achievement of a group of young talented people. At times it was terribly difficult, at times scary, at times gloriously creative and fun. Even though opportunity presented itself, I would choose never to work with Eagle again. I hold him in great regard, and mourn his passing -- Eagle Pennell, filmmaker, director, artist, imagineer.

-- Lin Sutherland, co-writer, co-producer, The Whole Shootin' Match

Working, Drinking, & Dreaming About Movies

It's difficult to summarize 20 years of working, drinking, and dreaming about movies with Eagle. He was just a Texas-sized guy, and as Larry McMurtry said of late Austin bookman and gambler John Jenkins (who partially underwrote Eagle's The Whole Shootin' Match), "Better to lose big than do nothing."

I was Eagle's "shooter" on Last Night at the Alamo. I think I was chosen because I came with the camera (...clair NPR) and the rifle (Winchester 30/30). He called me Crockett (we shared a love of Texas history) but he referred to himself as Fannin ... the so-called "loser" of the Texas Revolution. Eagle & Fannin shared similar fates in that they were both too human.

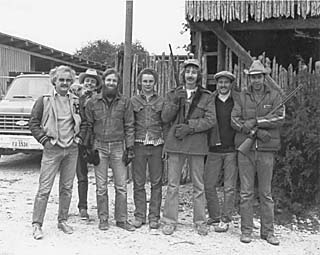

Good Memory 1983: "Get me a Preacher!" he roared over the phone during the making of Alamo, "I'm getting married!" The wedding party became rowdy when Eagle said to his new sister-in-law, "suck my dick!" (see attached photos of this moment). Eagle retreated to the street surrounded by angry waiters. Suddenly, he shouted Sam Houston's San Jacinto speech: "Gentlemen! Victory is ours. Stay calm & Remember the Alamo!" The waiters froze in their tracks & Eagle escaped into the night.

Bad Memory 2002: It had been his destiny to follow the hero's path. The last time I saw Eagle was a few days before the end. It was late and he was outside my apartment. I told him to go away and he shuffled off into the dark.

-- Brian Huberman, cinematographer, Last Night at the Alamo, and Associate Professor of Film Production, Rice University

The Man Who Made Himself a Movie Director

I was a partner and friend of Eagle Pennell, although, like many of his friends, I had put some distance between he and I for the last several years. I did the sound recording, design, and mixing for his first feature, The Whole Shootin' Match, and recorded and produced the music score (composed and performed by Eagle's brother, Chuck Pinnell) for Last Night at the Alamo. We also did a few smaller projects together, Eagle doing the visuals and I the sound and music. We had a lot of fun. I miss the enjoyable Eagle, but I've been missing that version of him for a long time.

In the newspapers, Alamo has been heralded as Eagle's pinnacle, and if so I think it is due in large part to Kim Henkel's deft touch as writer/producer. But, for a number of us who were part of the team back then, Shootin' Match is the real gem-in-the-rough, the unspoiled Eagle. The film's "heroes" are Frank and Lloyd, played by Sonny Davis and Lou Perryman. It was shot on weekends (most of us had day jobs) which allowed time during the week for Lou, Sonny, Eagle, and the actors whose scenes were coming up to meet, rehearse, and often reshape the story to fit the players. The actors would then bring magic with them to the weekend, and all we had to do was film it. Those weeknight sessions produced a wonderful movie.

It took me at least a decade to "see" Shootin' Match even though I'd watched it many times in the making and at festival screenings. Yes, it was shot in grainy black-and-white, with an aural equivalent on the release print's optical soundtrack, and yes, there isn't a lot of artifice in how it was made. Indeed, it was so unpolished I would wince when certain scenes rolled by, scenes I now find the most entertaining. Listen for the hilarious natural timing between Frank and Lloyd as they drive back from a job gone bad, and likewise between Paulette (Doris Hargrave) and Frank at the drive-in commenting on the fakery of movie acting. Both scenes are one-take wonders, obviously in a pickup truck simply sitting in a field, with little attempt to create the proper realism, and yet, it doesn't even matter because the characters are so enjoyable.

Eagle fell in love with these characters, and featured them in his three first films and would have put them in his next, The King of Texas, had it ever been made. In a way, he just kept making the same movie: part buddy-picture and part homage to a lifestyle left behind by modern times. It is Eagle's love for these characters and their little corner of the world that ultimately gives these films their heart.

I've been trying to forgive Eagle his excesses, which began to take hold as he basked in the success of Shootin' Match, and I've tried to forgive myself, too, for keeping him at arm's length once the excesses began to rule. Now that he has passed, I suspect much will be made of his bodacious, outsized character; the same qualities that can drive a novice from small-town Texas to proclaim himself a movie director, and then to actually become one, can also make for one hell of an overbearing drunk. For my own memories I prefer to focus on the films. They were fun to make and still fun to watch.

-- Wayne Bell, soundman, The Whole Shootin' Match, Last Night at the Alamo ![]()

The Austin Film Society and The Austin Chronicle present A Tribute to Eagle Pennell on Tuesday, Sept. 3, at the Alamo Drafthouse Downtown (409 Colorado). The Whole Shootin' Match screens at 7pm; Last Night at the Alamo screens at 9:30pm. "Hell of a Note" will screen before the 9:30 show. Tickets cost $4/AFS members; $6/general public.