Cast Away

Pure Castings, Zavala Elementary, pollution, jobs ... and the neighborhood

By Richard Whittaker, Fri., Aug. 28, 2009

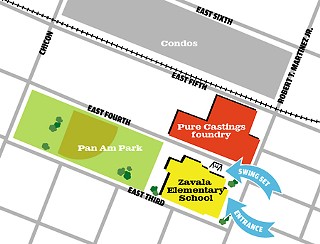

Since 1968, the Pure Castings Co. foundry has poured molten metal at its site on Fourth Street in East Austin. The owners have paid their taxes, kept up with their permits, and provided regular blue-collar jobs – all very conventional public virtues in 1968. But in 41 years, the idea that a factory might have any place in a residential area has steadily become anathema. Under current circumstances, the discussion of the foundry's future is raising larger questions about the future of manufacturing jobs in Austin. According to City Council Member Laura Morrison, "The idea was that it was OK to co-locate industrial and residential, and I think we're smarter than that now."

Perhaps so. Yet Pure Castings is probably not what many people would expect from a "foundry." The 35,000-square-foot facility fills about half a block on East Fourth with an unimposing array of industrial units. It produces small-order custom fittings – pipe valves, sprinkler nozzles, lock mechanisms – through the "investment," or lost wax, casting process. A metal mold is filled with molten wax; the wax sets and is repeatedly dipped into ceramic slurry and coated in sand. When the ceramic sets, the wax is melted and poured out, the metal is poured in and cooled, and the ceramic coating is pummeled away with a mounted jackhammer, leaving the metal set in the desired shape.

What worries Neil Carman isn't the metal in the smelter or the wax in the molds but the fumes in the air and their potential effects on the foundry's nearest neighbor: Zavala Elementary School. A 12-year veteran of the Texas Air Control Board (a predecessor agency to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality), Carman has spent 17 years as an environmental chemist with the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club and is now working with the Eastside activist group People Organized in Defense of Earth and Her Resources, or PODER. Much of his career has been devoted to examining sites like this. Under state and federal clean air statutes, Pure Castings is classified as a "minor source" because of its relatively small size and low emissions. As such, it operates under a TCEQ permit by rules, rather than applying for the kind of full, custom-written permit required for a chemical plant or a refinery. Carman's concern is not the volume of emissions, but the fine particles – 2.5 micrometers in diameter and smaller – produced by the facility. Known as PM-2.5, "They're so small, they're able to easily penetrate deeply into the lung tissues," he said. "You've got the microscopic nature of the chemicals, and the toxicity, that you don't want getting into the body." Especially, he argues, the bodies of small children such as those attending Zavala.

He's not the only one paying attention to Pure Castings. After a series of neighborhood complaints, TCEQ has sent three air sampling teams to the site since December 2008, and in February, the agency installed a PM-2.5 air quality monitoring station on Zavala's roof. The emissions can vary dramatically from day to day and hour to hour, but at their very worst, they've never risen above moderate air quality. That's the level at which TCEQ warns that "unusually sensitive people, such as those with asthma, should consider limiting prolonged outdoor activity." Matthew Baker, TCEQ's director of monitoring operations, said, "Everything that we have monitored for – which is pretty much the entire gamut of what can come out of a plant like that – has been below safety thresholds."

Still, with Zavala right next door, Paul Turner, Austin Independent School District's executive director of facilities, said: "Our antenna is up. ... It's undeniable that there's something coming out of there, soot and residue from the manufacturing process." But, he explained, the district has only TCEQ's measurements to work from, "and the conclusion has always been that we're within a level of tolerance." The district has also been keeping track of respiratory diseases on the campus, and so far, he said, "We didn't see any unusual pattern." In fact, based on students' reported visits to the nurse, Zavala is actually a little below the districtwide average. "But some of that data is hard to interpret," he added, "because sometimes you'll have a nurse who tends to react more and reports more."

Carman accuses TCEQ of "whitewashing" the levels of toxic chemicals, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, and their long-term health effects. "They identified 15 of them out there, 14 of which are recognized as carcinogens," he said. In addition, TCEQ's own testing has found 24 airborne metals, 12 of which are also carcinogens. Although the levels are within TCEQ's acceptable limits, Carman argues: "It's sort of like saying: 'A little bit of this bullet is safe, or a little bit of this bullet is OK. You just don't want to be hit by a big bullet.' It's just bogus. The only level that is safe with certainty is zero."

A Part of the Community, Apart From the Community

The only way to completely end emissions from Pure Castings is to close it, and owner Andy Edgerton has no plans to do so. "No one from the city has ever complained about us being here," he said. The issue, he says, is PODER, which he described as "eight or 10 people who have decided that their goal is to move us out of the community."

PODER's activists point out that Zavala was there first, opening in 1936 – but Pure Castings isn't a new development either. Edgerton himself has been there almost since the beginning, starting on the wax line in 1974 as an hourly employee; in 1992, he bought out the old owners. "It's basically the same neighborhood it's been since 1968," he said. "The only thing that's changed is just north of us – where the old railroad headquarters was, they've put in condos." He argues that PODER is clutching at straws by targeting his site. "They keep trying to find something that we're doing wrong, but unfortunately for them, they haven't been able to find anything," he said.

He's also cleaned up the facility. In the mid-Nineties, he hired an environmental officer, who spends one week a month at Pure Castings and the rest at Edgerton's sand foundry, Empire Castings, in Tulsa, Okla. He's installed additional dust collection systems, added smoke-combating afterburners to his burnout ovens, changed the solvents he uses, and, after a meeting with PODER and the city, changed the delivery schedules of his suppliers to reduce the amount of time they would spend with their engines idling. He even recycles the leftover wax. He also argues that it is unfair and inaccurate to suggest that every molecule of pollution comes from his facility or his vehicles. He recalls one incident when TCEQ asked him about a spike in readings from the Zavala station. "They asked me, 'What were you doing between 7 and 8 in the morning?' I told them, 'We weren't doing anything that we don't normally do.' It dawned on me later. That's when all the school buses drop the kids off."

Even with those changes, Carman's take is simple: "Pure Castings needs to clean up its act." There are options, like a bag house, "which is basically vacuum cleaner bags 20, 30 feet long," he said, or an electrostatic precipitator, which uses electric currents to pull dust from the air. For either plan, he said, "They're looking at spending some money." He concedes: "They have a right to be there. They just don't have a right to pollute the neighborhood."

Quality of Life

Others aren't so accommodating. PODER Director Susana Almanza has led the community charge to raise awareness against the presence of the foundry, first by going door-to-door in the neighborhood and then taking the campaign to City Council. She said: "People have felt like they can't open the windows because of the smell. But a lot of people in the neighborhood don't have air-conditioned homes, so they have to make the decision of whether they keep the windows closed or take on the odor."

As long as Pure Castings doesn't break emissions standards, it would seem that there's little to be done. But Carman argues that if TCEQ wanted to wield the big stick, it has one in its arsenal. "It's called General Rule 101.4, in the state statute, under the Texas Clean Air Act," he explained, but it's better known as the nuisance protocol. It bans any airborne pollution that can "adversely affect human health or welfare, animal life, vegetation, or property, or as to interfere with the normal use and enjoyment of animal life, vegetation, or property." Rather than depending solely on measurements, it allows for the experiences of those living around a facility to be considered. When he was still with the agency, he said, "We worked with the Attorney General's Office in a number of cases, when they put citizen witnesses on the stand who did a great job."

But such testimony remains subjective. TCEQ's Baker warned, "It's also subjective to the inspector saying: 'How much stink is too much stink? How much dust is too much dust?'" So far, TCEQ has not judged the site to have reached an actionable level of stink or dust.

Carman remains frustrated by what he sees as a lack of depth and scope to TCEQ's reporting, like monitoring chromium levels but failing to differentiate between the harmless chromium III and the toxic carcinogen hexavalent chromium. He particularly points to TCEQ's failure to talk to residents about their health. "Any time you investigate a complaint, you ask, 'Do you want to complain about any health effects?' ... But the TCEQ failed to document this in any of their reports." If they had, he argued, the case for cracking down on Pure Castings might be stronger.

Edgerton doesn't think the issue is the emissions: "If I totally enclosed this building, and nothing got out of here, then I still don't think PODER would be happy," he said. On the contrary, he suspects this campaign is really just about his land.

If Not Here, Then Where?

For PODER, the solution is simple: Close Pure Castings and turn the land over to "affordable housing." The group wants the city to tap the $55 million in affordable housing finance bonds passed by voters in 2006. So far, only about $16 million in projects has been approved, so there are big reserves. "There's no reason why that money can't be used to buy that facility," said Almanza. "I think the ball is in the City Council's lap, and the council is dragging its feet."

The city has taken some action: On Feb. 5, the 2006 Bond Election Advisory Committee requested further information on both emissions and using the site for affordable housing. The TCEQ study was already ongoing, but there has been no movement on the bond money issue because the Neighborhood Housing and Community Development office has not received a direct instruction from either council or the city manager's office to explore this proposal. As the current zoning stands, should Pure Castings move or close, it will not be replaced by another factory. When it was built, the land was zoned as light industrial. Under the 2001 Holly Street Neighborhood Plan overlay, it was rezoned for commercial services, but "the zoning would not kick in until they were closed or sold," Almanza explained. There are hundreds of similar grandfathered tracts – 14 in the Holly plan alone – and the process can be slow. In 2007, the nearby Holly Street Power Plant closed – five years after council ordered that it be wound down and two years ahead of schedule. "We've closed down some of the larger [polluters], but there are still some that are just as hazardous and impacting the most vulnerable population," she said.

Council Member Morrison explained, "In some ways, zoning was developed because we had industrial and residential next to each other." It's not just about getting manufacturing out of neighborhoods. Council recently rejected an application to rezone an industrial property on MLK Boulevard as single-family housing. Morrison explained: "The concern was that, if the long-term future of this area is industrial, how can we down-zone to single housing? We're just putting in place the possibility for future conflict."

Even Edgerton has made gestures toward potential relocation. While he doesn't have any imminent plans and isn't under any immediate pressure from the city, he's not perfectly satisfied with the current location. Because the site has expanded piecemeal over the last 41 years, he said, "we don't have a smooth flow. Our process starts in the middle building, it comes to the west, and then goes to the east building. ... Like I told [Mayor Pro Tem] Mike Martinez when he asked us, 'Would you guys be willing to move?,' I would love a new facility."

So if PODER wants him gone and Edgerton isn't averse to moving, what's the problem? Like Carman's proposal for additional filtration, it comes down to money.

Part of the argument now is about how much the property is worth. In the latest tax assessment, Travis Central Appraisal District valued the site at a little over $1.7 million. That's just the property, not the business, and moving a foundry isn't like moving an office. Edgerton explained, "You'd have to build a new facility and move one department at a time." He had a consultant price up the cost last year: "You're probably looking in the region of $5 million."

That's a sum he simply can't afford. Due to the recession, he estimates that production is down around 35%, and he's down to 60 employees; last year, he had 85. There have been some good signs: Around two-thirds of Edgerton's business comes from the oil industry, and after almost a year of large numbers of rigs going offline in North American waters, the rig count is slowly rising again. It's nowhere near enough for him to consider a move without some form of assistance or incentive. "Ten, 15 years, if business is good," he said, "we might be able to look at something like that if we grow."

So even if the city does intervene to move or push all polluting industry out of the neighborhoods, this still leaves one question: Where would they go?

Post-Pollution Industry

It's a conundrum. Air quality is a major concern, and it seems almost inevitable that the Austin-Round Rock metropolitan statistical area will fail to reach the new, tougher Environmental Protection Agency ozone standards and be placed in nonattainment status next year. While much of that pollution comes from private vehicles and domestic energy usage, industrial polluters like Pure Castings play a role.

Yet Austin isn't trying to turn its back on industry. Part of the discussion around developing a 50-year Integrated Solid Waste Management Master Plan (see "A Plan to Plan for a Zero-Waste City," July 31) revolves around attracting green-collar manufacturing and recycling. At the moment, the city sells all its recyclables on the open market, much of which will then be shipped to China. If the city can encourage businesses to recycle and reuse locally produced waste here in town, Solid Waste Advisory Commission Vice Chair Rick Cofer said, "we can close the loop."

But a green product doesn't always mean an emission-free production process, and even having the cleanest, greenest factories on the planet doesn't necessarily help if the workers have to drive halfway across the county to get to work. So Morrison advocates the construction of green-collar manufacturing industrial parks outside of residential areas. "The idea is to centralize them far enough away from residential areas that they are not impacting them but near enough that they can be in commuting distance," she suggests. That will take time. The city has discussed a major green industrial park and incubator as part of a proposed materials recovery facility (see "City Adds Costs and CO2 to Recycling Program," Oct. 24, 2008). So far those discussions have produced little result, and the city is still waiting on a delayed report on the proposal from consulting firm R.W. Beck.

At the state level, the picture isn't much better. Rep. Eddie Rodriguez, D-Austin, lives in the Holly Street neighborhood, and as a member of the House Technology, Economic Development & Workforce Committee, he has a keen interest in bringing green-collar jobs to his community. But he called the last session "a complete failure" in terms of creating policies to attract and promote green manufacturing and warned that the city will have to take the initiative to attract and retain those firms.

There have already been losses. In April, Austin-based Solar Array Ventures announced the location of its first big solar panel production facility: Bernalillo County (Albuquerque) in New Mexico. The firm took 215 new factory jobs with an average wage of $48,000 a year and an annual payroll of $11 million with them. The reason was larger incentives: Bernalillo County commissioners offered the company a $175 million industrial revenue bond for construction. Rodriguez explained, "You can't compete with that kind of money, so you counter it with something else." He suggests Austin has a built-in advantage in attracting green manufacturing – it's a ready-made market. "The population, by and large, supports green energy and green jobs. They want solar in their house, they want to weatherize, and that's a really good first step," he said.

It's also an opportunity for Austin to hold the state to the new educational standard that high school students must be post-secondary ready, not just four-year-college ready. Rodriguez points to the Green Corridor Collaborative, a recently signed agreement be-tween Austin Community College and four other community colleges along the I-35 corridor, which will use federal stimulus money to develop green-collar skills programs. Austinites could benefit from these programs, especially the blue-collar community of East Austin and the students at Eastside Memorial Green Tech High School, one of the two new schools on the former Johnston campus. Rodriguez explained, "You could have a mechanism where students could, through high school, maybe do a few extra months training, graduate with the appropriate certification, and they're ready to go to work, whether it's weatherization or manufacturing of solar."

In the meantime, with those plans for a green industrial sector still on the drawing board, Austin has to work out what it's going to do with established firms like Pure Castings. Until PODER finds the smoking gun it's looking for, or the foundry closes or relocates, Edgerton said, "We're caught in the middle of that argument, but we've learned to live with it."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.