Lone Star Sweden

Lars Gustafsson

By Roger Gathman, Fri., Feb. 25, 2000

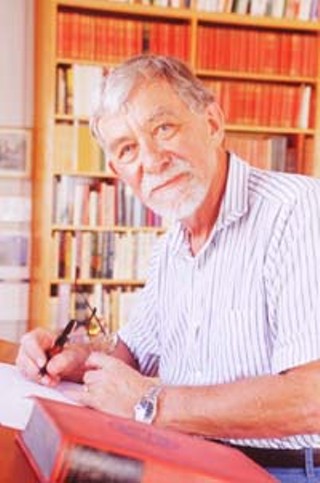

Critics have often remarked on the odd but fruitful relationship between exile and writing. Our supreme example, in the now-past century, is perhaps the long, exacting homesickness that drove Joyce to devote his imagination to a June day in Dublin, while teaching or living on handouts in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris. The less-noted side of the equation is the exiled writer who lives and interacts with people who don't recognize him -- who are sometimes even barred, by differences of language, from recognizing him. One wonders what students in the Berlitz school in Trieste thought of Signore Joyce. Did anybody in the Forties at Harvard's entomology department realize that Vladimir Nabokov, that odd Russian lepidopterist down the hall, was one of Russia's greatest modernist writers, or have an inkling that he was about to become one of America's greatest? How many of us realize that Austin has a definite place in contemporary Swedish literature? Probably not many. One of the most highly praised of contemporary Swedish writers, Lars Gustafsson, the author of Bernard Foy's Third Castling and numerous other works of fiction, poetry, and philosophy, has lived here, quietly, for 20 some years. In that period, he has included Austin not only as a reference in his work, but increasingly as the locale within which his plots go forward. His most recent work to be translated into English, The Tale of a Dog: From the Diaries and Letters of a Texan Bankruptcy Judge, is in fact completely set in Austin. It is the first novel in a trilogy that focuses on Austin characters. Gustafsson's narrator is Erwin Caldwell, a Texas bankruptcy judge, who lives on a house above Town Lake and comments on Austin real estate and UT intramural politics. He is peripherally, or maybe centrally, involved in a murder -- depending on your point of view. The district attorney meets him at Mozart's. All the characters shop at Whole Foods. What the Swedes make of all of this is one of the puzzles I wanted to ask him about.

His own story about his first impression of Austin has something irresistibly humorous about it -- a matter of almost imperceptible incongruities that are the hallmark of Gustafsson's mature narrative technique: "Austin has a big role, to say the least, in my life, without my really intending it. I came the first time in 1972; I was on a poetry reading to American universities. And they had some seminar here in Austin. It was in the beginning of May, and I stepped out of the airplane, on the stair, and I felt like returning into the airplane because it was too hot. I was received by two very bearded gentlemen who were the professors of Swedish at the time and then I took part in the conference and I was asked if I wanted to come back. So I came back in 1974 and wrote The Tennis Player."

I see those two bearded gentlemen, the heat, and the lithe Swedish poet encountering a 100-degree spring day such as he'd never dreamed of stepping into, as figures in a parable of obscure intent. And that is much the way Gustafsson has written about this city.

Bernard Foy's Third Castling is the novel for which Gustafsson is most known, internationally. It is the kind of meta-fiction which one associates with Italo Calvino. The novel takes place in Sweden, Paris, Worpsewede, Germany (the town which, in 1900, hosted an art colony where Rilke met his wife), and Texas. Bernard Foy is the name of three characters, one of them a Houston rabbi, one an old, established Swedish poet, and one a young Swedish teenager. The novel's sequence is to dissolve each Foy into a character in the writing of a succeeding Foy. This superstructure frames a series of detective story plots, which refer, obliquely, to poems by Rilke and Baudelaire. The novel was published in 1984 and became a big European hit. Gustafsson has said before that it is the best novel he has written. When I asked him whether he had written it in a library in Austin, as I had been told, he said: "It started with a conversation in a pub in Cambridge. I was talking to a young philosopher named Mark Sacks. He said he was going to a conference on fiction, and I said, 'What do you mean, on fiction?' He said, 'By fiction I mean a system which is part of a greater system where you cannot, as long as you are inside the departure system, you cannot decide whether it is a part of a bigger system or not.' Something said 'pop' in my brain. Of course I saw the connection to Descartes' dream argument: You start with a story and it proves to be the story of a completely different person who is dreaming up the story which proves to be the story of a third person and it is all written by one or another person. Then I was going with my wife from Stockholm to Paris on a winter evening with my older son. When we climbed into our [train] compartment, he said, 'Can't you write a novel where the secretary of the Swedish Chess Association is murdered?' And I did it. It took three years," and it was completed in the basement of the geography building on the UT campus. "I wrote a poem, the 'Geography of the Geography Department,' and I wrote most of Bernard Foy there," Gustafsson says. "I started on typewriter and then finished on computer."

One day last December I went to Gustafsson's house in Tarrytown to interview him. The house is a large, comfortable structure that contained a menagerie of birds, cats, and dogs; but perhaps Gustafsson himself is the most exotic beast of all. He is a small, white-haired man with wire-framed glasses and a Van Dyke beard which brings his thin face to a point. He speaks with that rolling accent which reveals that the words are layered over a subordinate flow of Swedish rhythms. He has the air, somehow, of a sailor; it is as though he were some Swedish Sinbad come to rest here after a dozen ports. And in a way, that is true, for he has been an indefatigable traveler, in Europe, Africa, and Australia, as well as the United States.

At least in Austin the realization is slowly sinking in that Texas has grown a Scandanavian extension. Gustafsson, a philosophy and Germanic studies professor at UT, was invited to speak at the Texas Book Festival last year as a more or less Texas writer. Gustafsson still retains his stature in Sweden, but he seems to be getting used to his gradual acceptance as a Texas writer:

Austin Chronicle: What do your friends, or critics in Sweden, say about placing your stories in a place like Austin, which isn't that big? It isn't like everybody in Europe has heard of us -- don't they find that sort of weird?

Lars Gustafsson: This is pretty interesting, because it is a modern phenomenon of the transcontinental novel, like Rushdie. So there are Pakistanis in London, or Kurds who live in Stockholm, and I've been told that the majority of Kurdish contemporary literature is written in Stockholm.

AC: Do you wander around Austin -- do you think of yourself as an Austin flneur?

LG: Well, yes, except on bicycle. A real flneur doesn't use a bike. Anyhow, a typical Yankee, the New York critic, writes that such and such isn't authentic, because they haven't seen Austin. Austin has a very special flavor, and if you've spent your life in Brooklyn or Queens, you can't imagine Austin. Austin has a fantastic quality, a magic quality. I found kindred minds about this recently because I was invited for the first time to the Texas Book Festival and they didn't know quite how to place me. So they placed me on a panel with lawyers and judges who had written detective stories.

AC: Because you had a bankruptcy judge in The Tale of a Dog.

LG: Anyhow, this had a lot of advantages. First, it was the best panel of writers I'd been to in my life because they listened. They had all written novels about strange murders in Austin. One of them had a novel which ended in the very old systems of tunnels that go under Sixth Street. And all of a sudden I was with people who understood my Austin better than I do.

AC: Well, Sweden is such a contrast with Austin.

LG: An enormous contrast. I travel back; I'm no Solzhenitsyn. I spend approximately one and a half months every summer in Sweden. I have a summer house. More of a cabin. I was even on the board of regents of Uppsala University for four years. So I move between these two worlds with a certain ease. If I had stayed in Sweden all my life, I would have become a less interesting writer.

AC: The Tennis Player is the first novel in which you feature an Austin setting. You used the Lars persona in The Tennis Player, as you did in your earlier novels. Then you stopped.

LG: The background to The Tennis Player might amuse you. You might have observed that it has six chapters of exactly the same length. This is not a coincidence. Swedish television, which had made films from literary manuscripts for many years, was going through some sort of economic crisis; it was a state institution. A producer friend of mine, Christian, had a brilliant idea. He said, "Let's stop this nonsense of making bad films of manuscripts, let's just invite the writers to read their manuscripts into a camera." Everybody said "Goddamn boring." We made some experiments, asking writers to write a summer tale, and then to write a winter tale, using a number of different writers. We wanted to do the most rash experiment, so he seriously asked me to write a story which could be read for every evening for 30 minutes for one week. I said "Good Lord, it is as difficult as writing a sonnet. You have to use a carpenter's level of precision." So I sat down and I should say I've never in my life written anything that fast. I think it took 20 days. So I wrote down my own experiences in Austin. I had several ideas. I think the worst idea was the European who becomes more and more Texan, and his Texan students who become more and more European.

AC: For some reason, in the Seventies, the Swedish produced all these great tennis players. It was Borg's era.

LG: Bjorn Borg tried to read The Tennis Player, but he was such an extremely unintellectual person, he said, "It looks amusing but is it easy to read?"

AC: I've heard that you feel like you escaped the conformism in Sweden. That coziness.

LG: Yes. There are conformists everywhere, but it is nice that here I don't have to mull that much about the situation, here I take care of my university duties and then I do my various things.

AC: Because it is a small country, I imagine the pressures to conform --

LG: You get a lot of pressure; it is surprising. And I don't believe that Sweden is an exception, this is the same thing that happens in a lot of small countries, like Austria. I happen to have a lot of friends in Austria and they talk about the conformist pressure. Hans Magnus Erzenberger is an old friend of mine, he was the first to translate my poetry into German. Well, Magnus wrote a book named Europa, an excellent book, wherein he plays with the idea that it isn't the same time in different parts of the world.

AC: Well, you talk about that too. For instance, in The Tennis Player.

LG: Well, Erzensberger has a different idea. We have isoclines and isobars, you know. Well, he plays with the idea of isochrones. He says that of course, it isn't the same time in Portugal and Paris and London. If you go to some places in Europe, it is almost 1900. It is a funny idea and I like it.

AC: You returned to Austin for good in 1979?

LG: Then I found my present wife, Alexandra. We met at an international seminar outside Copenhagen. I think in '79. When she told me that she came from Austin, Texas, I was so glad to hear that. She was studying in Cambridge at that time. She was into Greek philosophy with a student of Gwyl Owen [ a Cambridge professor]. But he died. She married me. She tried to live in Uppsala, which was good from the human point of view, but philosophically difficult, since they were only making modal logic. And I got a very good offer, and it was on her plea, and I said, "Okay, what should we do now?"

AC: You'd gotten an offer to teach here.

LG: Yes, to be a professor. I have never wanted to be a full-time professor. I could have gotten tenure I suppose if I had tried. But I've become some sort of honors professor. I'm an advising professor in the Plan Two program. I'm a "Distinguished Professor," but I never use that title. I see a lot of humor in that. ![]()