Miss Montana's Wedding Day

Third Place

By Amanda Eyre Ward, Fri., Sept. 17, 1999

The man Vera loved wasn't marrying her, and she didn't know what to wear to the wedding. For one thing, it was cold in Montana. That ruled out the scorned woman in a silk dress idea. Also, she would have to wear boots; it had been snowing for weeks. The sun had come up, but it was still dark outside: a gray day. Vera's apartment was covered in a filmy light that made everything look dirty. She found a cigarette in a crumpled pack, and the nicotine warmed her arms and legs.

Outside her windows, the tops of the mountains were white: new snow. Next to her bed was an empty wine bottle and a thin crystal glass mottled with red. A darkness filled her, and she tried to focus on small, good things: she could eat ice cream for breakfast, if she wanted. It was warm in her bed. Chocolate.

Jeans were out: Vera would look as if she were trying to look as if she didn't care. Of course she cared! And all she had for fancy was an old prom dress in salmon pink. Every item of clothing made Vera think of Henry: the green teddy he had bought her for St. Patrick's Day, the tight jeans he liked her in, the skirts he'd whistle at in the halls when he saw her coming. What use were they? He was marrying Miss Montana. Miss Montana was gorgeous. She had a tiara, and a Ford truck with MISS MT on the license plate.

Henry. The fine arc of his nose, the beard that smelled of soap, summer sky eyes. His hands on Vera's hips, his lips soft and hot. Henry was finishing his dissertation: "Beckett in Love." Miss Montana was carrying his child. He had told Vera, and she had promised not to tell anyone else. After everything, Vera owed him that.

(Her therapist, Maureen, said she didn't owe him anything. Vera had to "take care of me," said Maureen.)

In the bathroom mirror, Vera's face looked tired and old. She was twenty five, and knew that she should feel the beginnings of her life beginning to sprout. Instead, she was an old salad, wilted and tasteless.

She was a filmmaker who hadn't yet made a film. In the meantime, she worked the cop beat for the local paper, the Missoulian. It wasn't a happy job: domestic violence, metamphetamines, pot busts. She wanted to make a film about the American dream, but she was caught up in the details.

Vera decided on slacks and a sweater which reeked of mothballs. She had packed all of Henry's things (shirts, books, casserole dish) into a cardboard box and had mailed it to the house he and Miss Montana had bought with her winnings. The house was a half-minute walk away, but, as her therapist Maureen said, there was a sense of closure about mailing something. Vera had even sent it first class, telling the man at Mailboxes Etc. that it was her ex-lover's belongings. The man was Native American, and a long braid hung over his Mailboxes Etc. gingham smock.

"You could have burned these things," said the man. "He is lucky."

"He's an asshole," Vera said. The man looked at her sadly. She leaned forward conspiratorially. "He's marrying Miss Montana," said Vera. She raised her eyebrows.

"Miss Montana?" said the man. "Come around here," he said, and he led her to the back room and there she was, Aubrey Halliwell, Miss Montana 1999, in a red white and blue spangled bikini waving a lasso. "I hate that fucking poster," said Vera.

"She signed it for me," said the man. He couldn't take his eyes off Aubrey, and her winged-out hair. And there it was, in curlicue script: TO GEORGE.

Vera closed her apartment door behind her and rang for the elevator. She lived in an old building, and the elevator was still run by people instead of machines. Vera waited a minute or two, and then the door to the apartment next to hers banged open. The door had a cardboard sign taped to it: BEAUTY SALON, and it was no joke. The lady who ran the elevator during the day, Bea, got her hair done while she waited for the elevator bell to ring.

"Hi, honey," she said, closing the BEAUTY SALON door behind her. She had curlers in her shocking orange hair, and a bathrobe over her large frame. She stepped into the elevator barefoot. "Where you going?" she asked.

"You don't want to know," said Vera. The elevator was covered in threadbare red velvet, and Bea's chair was gilded gold.

"I do," said Bea, though she seemed more interested in her nails.

"Remember my boyfriend?" Vera said, "The tall one with the beard and the glasses?" Bea nodded, patting her hair. "He's getting married," said Vera. "Not to me," she added.

"Should I get Lee Press-On Nails?" said Bea, holding out her hands.

Vera didn' t answer. The elevator stopped with a jolt and Bea lifted the bar slowly and heaved open the doors.

"You know who else is getting married today?" said Bea, "Is Miss Montana."

In Pat's Hiway Café, Vera ordered toast. She was surrounded by men drinking. Pat's was connected to a bar, and men passed back and forth between the two. What the hell? Vera ordered a beer.

Her toast dripped with butter. She spread jam over it, chewing slowly. The snow had turned to rain, and she had to walk to the wedding, ten blocks or so away. Her coffee was thin. Her therapist Maureen told her to pretend to be normal, and to make a mental note of when she felt like acting crazy, but acted normal instead. Mental note: she sat and ate her breakfast, and did not smash the windows of Pat's Hiway Café with her fists.

The church was completely full, and there was no room for Vera inside it. She wedged her way between two teen girls with Brownie box cameras. "Ow!" cried one. "That lady with the wet hat like stepped on my foot!" Vera shoved her aside, and found a seat in a pew next to Jodi Lewis, the martini-drinking piano player from the Holiday Inn lounge. Henry and Vera had loved the Holiday Inn Lounge. They had the same favorite song: You say potato and I say po-tah-to--

"Your hat is dripping, honey," Jodi said to Vera. She wore a red muumuu.

"I don't care," Vera said. Television cameras were set up along the aisle, and people held cardboard signs: WE LOVE YOU AUBREY! MONTANA FOREVER! MARRY ME INSTEAD! What was the matter with these people? Mental note: Vera did not scream aloud.

Henry and Vera had come to this church once, for Easter. They had been drunk the night before, and had fought so long and so hard that they couldn't remember what was wrong anymore. In the pew, while the choir sang like angels, Henry had taken Vera's hand, held her bones carefully. "We are going to make it," he had said.

In the back of the church, next to the life-size figure of Mary, there was a flurry of microphones and cameras. Pale shadows from the stained glass windows made the chaos into a kaleidoscope, and in the middle was Henry. He was freshly showered (Vera could not help but think of his wet nipples, the feel of his round buttocks) and wore a white tuxedo, too large and shiny. Vera had never seen him in a tuxedo before, or even a suit for that matter. He had always worn frayed shirts, and corduroy pants. He smiled, looking afraid and vague.

There was a hush, and the music began. Vera looked around the church. People's eyes shone, and hands were held to mouths in excitement. Although Aubrey could be seen around Missoula a few days a week, at ribbon-cutting ceremonies or auto shows, seeing her on her wedding day was something people would talk about for years to come. The paper had been analyzing her dress choices and discussing honeymoon spots around town (she had opted for Fort Lauderdale, and to hell with Montana, but people still loved her). The reporters on the wedding beat had all apologized to Vera, in the bathroom or the cafeteria. "Fucking ridiculous," admitted one, an old man who later got the front page for revealing Aubrey's hairdo choice for the big day.

The hairdo choice was ringlets. Tendrils and curls and loops with flowers stuck inside them. "On the most important and loving day of my life," said Aubrey, in an exclusive interview, "I want to look like a summer fairy, to show my beloved that we will have days of summer always. In our hearts, I mean."

The bridesmaids came in slowly, in powder blue dresses with hoop skirts. They held bouquets of blue-colored carnations, and there was nary a ringlet among them. Carnations were Aubrey's favorite flower, she had revealed in the exclusive interview, because they "could be dyed any color of the rainbow."

Henry made his way to the front of the church. His loping gait was the same, and he looked down at the petal-strewn aisle. Vera felt a scream inside her, and as if on cue, trumpets blared. In came Miss Montana.

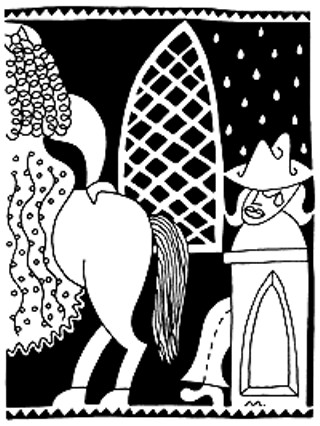

How she had gotten permission to bring a horse into the church Vera did not know. But there it was: a white steed, its saddle bordered in carnations. Atop the horse, sidesaddle, was Aubrey. Her dress was a marshmallow confection, swirls and dips of taffeta and tulle like a Dairy Queen ice cream. The dress moved, it rustled and slithered. And Aubrey burst out of it, her skin, in January, a triumphant orange. Her teeth glowed, and she wore enough blue eyeshadow to drown a man. From her ringleted hair exploded a fountain of filmy veil. In one hand was a glorious bouquet of carnations dyed every color imaginable. In the other, a lasso. As the band struck up the University of Montana Grizzlies fight song, she spun the lasso high above her head and aimed. The crowd grew silent.

And what do you know, the toast of Montana lasso-ed herself a man. Vera's man: Henry. Vera put her hands to her face, feeling his shame. Henry, his quiet voice, his warm hands. She remembered the night they had read Antony and Cleopatra aloud. She turned to look at him, her love.

In a lasso of gold and a white tuxedo, he was beaming. His chin was lifted high, and his eyes were bright. He looked at Aubrey with all the joy Vera had never thought was in him.

***

Abe shrugged and poured the whiskey. "What?" Vera said.

"Isn't dark yet," said Abe.

"It's dark in here, and that's for sure," said Vera. Abe shrugged again. The neon beer signs made his face shine, and he ran a palm over his thinning curls. On either side of Vera, men with sunken faces drank and stared forward, at the dusty bottles, at nothing. There was one woman with a glass of white wine. Her hair was a helmet of white curls. At night, the bar was filled with students and the click of poolballs, but for the afternoon crowd, there was only the hum of the heater, and a sour smell of disappointment.

"He did it," Vera said, "He tied the knot, all right." Abe nodded. He knew everyone's stories. In fact, he had probably seen the night that Henry went home with Miss Montana instead of Vera. "Do you watch people, Abe?"

"Vera?"

"Do you watch people, I said. What they do, how much they drink, etc." A man with a large wet gash in his cheek looked at Vera sideways, and moved over a stool. The white wine woman looked up.

"Course I do," said Abe, "What choice do I have?"

"I bet you could tell some stories," said Vera.

Abe took a toothpick from a box underneath the counter and put it in his mouth. "No," he said. "Not really."

"Can of Bud," said a man. He had been sitting in the back, and now came up on Vera' s left, and leaned his elbow on the counter. His cracked leather jacket smelled like sweat. The man was old, and had the smallest feet Vera had ever seen, in the smallest pointy boots. A large beige hat rested uneasily on his small head. Abe cracked open the can with a sharp sound and set it on the counter. The man pulled out some dirty bills, and then twisted the can tab back and forth, waiting for his change. He finally broke the tab off and left it on the bar, taking a swig of his can on the way back to his table.

"Come on, Abe," said Vera. "What about love stories?"

Abe shrugged, and out of the corner of Vera's eye, she saw the white wine woman reach out. Her lips curled up -- a flash of smile, and then it was gone -- as she took the beer tab in her fingers, and then stuck it behind her bra strap.

"Love stories don't happen in this town," said Abe. ![]()