The Slow Dying of Johnston High

Pride of the Eastside struggles to survive

By Kimberly Reeves, Fri., Nov. 30, 2007

The night Austin state Sen. Kirk Watson urged the community to pull together to save the pride of the Eastside might have been a turning point for Johnston High School.

It was Oct. 3, just a month into the school year. The overheated Johnston cafeteria was crowded with people focused on the success of the school – from members of the Greater Austin Hispanic Chamber of Commerce to key officials in the Austin Independent School District to a table full of Texas Education Agency staffers who would deal directly with the Johnston "intervention." Student leaders were also on hand, among them senior class President Gabby Camarillo, ready to take the microphone to urge classmates not to give up. The final attendance count would be 400 people – impressive for a school of only 700 students.

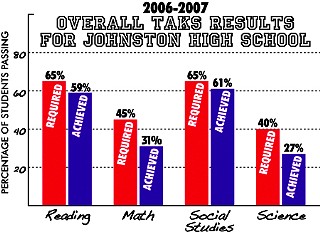

Watson exhorted the group to do whatever it takes to turn Johnston around, after four years of dismal standardized-test scores. The state's accountability system, once merely onerous, now carries serious consequences for schools that don't meet minimum expectations. This year Johnston – like Sam Houston High School in Houston, Oak Village Middle School in North Forest, and G.L. Wiley Middle School in Waco – faces the real threat of closure if test scores don't rise to acceptable levels.

"We can and we will succeed, if each of us and all of us are dedicated," Watson told the group. Then, he added a warning: "You must merit staying open. All of us, my friends, must be dedicated. The stakes couldn't be higher. We are talking about the lives of our children. Johnston will succeed only if everyone in this room plays a part."

Johnny Townsend, youth pastor at Solid Rock Missionary Baptist Church, stood amidst the crowd at the back of the room. Solid Rock is just two blocks up the street from Johnston, but not a single member of the church's youth group attends the high school. Instead, most have chosen to transfer to other AISD schools, such as LBJ and Austin High.

Afterward, Townsend said that as he listened to Watson, he realized it was all over for Johnston. "From my standpoint, this wasn't a pep rally. It was a funeral," said Townsend. "The senator said one word that stuck with me, and that was 'merit.' The school would have to merit staying open. As far as I was concerned, if you hadn't been able to do something in all these years, then four to six months is not going to make a difference. As far as I could tell, this was just closure – so the senator could say, as far as politics are concerned, 'I tried to help.' And the guy who has to close the campus could say, 'Well, I came out and saw the campus.' There's no doubt in my mind the campus is going to close."

Homecoming Busters

Rocky Medrano stood in the library of Johnston High on a cold November night just over a year ago, agitated and just a little bit upset. The former boxer and onetime constable was joined by several members of the school's tiny alumni association, all of whom wanted to know just what needed to be done to save Johnston. "I would die for Johnston High School," said Medrano, dramatically spreading his arms for emphasis as he asked if everything possible was being done to save the school.

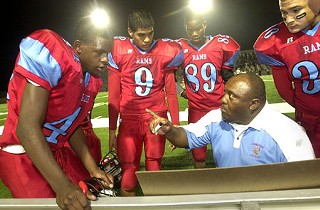

He's not the first or the last to pledge to save Johnston. Sam Guzman announced his candidacy for the Austin school board in front of the 47-year-old Johnston High. Getting Johnston back on track, Guzman said, would be his top priority, and the vow helped him win the election. Guzman says he remains optimistic, but it's not clear what that means for the school in practical terms. "I think about the last football game, and I think about the spirit the team showed on the field, the fight they had. I know the coach and the principal told them, 'You're part of the leadership that's going to push this school forward,'" Guzman said. "We've got a lot of work to do, but I'm still optimistic that we're going to pull through."

Superintendent Pat Forgione says he has not lost faith that Johnston can turn itself around this year. He points to some promising benchmarks: 80% of the teachers returned, the principal is back for a third year, and the district has committed significant resources for this year – $10,000 per student compared to $6,000 at Austin High. "I'm not losing faith, but it's very challenging," said Forgione, adding that the school's problems have been three decades in the making. "We'll face what happens this spring, but we're not giving up. You don't give up on public schools. We're committed to neighborhood schools. And if we're not successful this year, we will accept accountability."

But will Forgione's renewed commitment, Medrano and Guzman's passion for Johnston, or the pledge of support from Paul Saldaña of the Greater Austin Hispanic Chamber of Commerce – be too little, too late to save the pride of the Eastside? Enrollment has been dropping steadily, from a peak of more than 1,800 students just over a decade ago to barely 657 students this year. Coach Demo Odems struggled to field a football team this season with enough depth to make it through four quarters on Nelson Field. The band, once 90 students strong, barely marched a dozen at Nelson Field during homecoming against Lanier High, and that included three volunteers from a local drum-and-bugle corps and two Huston-Tillotson horn players. Probably a third of the stands were filled for the Rams' homecoming game, and many students considered it the best attendance in recent memory.

Roll the clock back to 1992. That year, then-drum-major Mike New remembers, Johnston was called the "homecoming busters" because every team in the district had scheduled Johnston for homecoming, and nearly every one of them lost. The district championship game, against the LBJ Jaguars, was going to be a nail-biter. On the opposing team? Demo Odems, who remembered Johnston as a fierce and competitive team.

New remembers the bright lights, the full brass section and drum line, his measured strides to the center of Nelson Field. He remembers his slow pivot on the field to face the home-team stands and the massive sea of Columbian blue and red that stretched from one end to the other. This was the underdog – Johnston High School – showing people just what the school was actually made of, New thought. "I'll never forget it," New said, then added wryly, "I don't know if we've sold out a game since."

But it's tough for kids to feel that kind of Eastside pride this year. Only days after Johnston agreed to forfeit much of its football season due to too many injured or ineligible players – and a week after the town hall meeting in the Johnston cafeteria – the newly formed PTA gathered in the school library to talk about the school's challenges, football among them.

Principal Celina Estrada-Thomas – already burdened with the knowledge that more than a dozen football players would be held out from the team the following week due to failing grades and faced with growing signs of a significant post-lunch attendance problem – had to face parents who felt both bruised and angry, saying they were being punished for choosing to keep their children at Johnston High.

"First and foremost, I cannot apologize enough for the turmoil and just the hurt feelings over this decision," Estrada-Thomas told the crowd of about two dozen parents and a handful of students. "I would hope that all of you know, by now, that decisions here are made in the best interest of the kids, and I would never set out deliberately to hurt anyone or create a problem for this school. ... We have their best interest at heart."

Art Jimenez's mother, Anna, was stricken at the news. Her son, an offensive and defensive tackle who had played football since he was 5, was about to see his entire senior football season thrown away because of Johnston's troubles. Maybe, Jimenez said, she should have transferred her son to Crockett High when she had the chance. "I know the situation. I know we did not have any choice, but there has to be some type of exception for him," Jimenez told Estrada-Thomas. "I don't know why the district is doing this to our school, why we have to suffer. No one is advocating for us, for him. I want him to finish his season as a varsity player. Someone needs to fight for that for him."

Jimenez's sadness and disappointment – over her son's season and, indirectly, over the failure to turn Johnston around – has been reflected in a lot of faces lately. New, who has coached the struggling drum line for no pay for three years now, watched other high school band directors circling the Johnston band hall, picking over the school's equipment in anticipation of a closure that still has yet to be averted, despite all efforts.

"I just want to be sure to get the band pictures," said New a bit sadly, strapping on his snare drum in the Nelson Field parking lot before he marched in with the band at the Lanier game. "I want to make sure those don't get lost."

A Mountain to Climb

Take all the high schools in the state – from the predominately white enclave of Highland Park to the toughest inner-city ghettos of Houston's Fifth Ward to the challenges of a transient, non-English-speaking population along the Texas-Mexico border – and consider this: Only two high schools in the state have performed so poorly, for so long, that the state has marked them for closure. One is in Houston's roughest neighborhood. And the other is Johnston High School.

What happened at Johnston is not typical. Most schools that end up on the state's list of low-performing schools do end up turning themselves around. School leaders take notice. District officials do what it takes to intervene. In fact, Texas Education Agency statistics show that eight out of 10 schools that are put on the watch list in the first year – be it for test scores or even dropout rates – won't be back on that list the next year.

While other schools have scored lower on the state's standardized tests – comparable scores at Reagan, for instance, were well below Johnston in both language arts and math last year – it's Johnston that will pay the price for dismally and chronically failing the exit-level Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills. Under state law, Johnston should have been closed this year, after three years of low performance, but Commissioner Robert Scott agreed he would wait another year before deciding to close it. "I don't want to make that decision this spring," Scott told the crowd at Watson's town hall meeting in early October. "This is the year. This is our shot. This is meeting the kids where they are and propelling them forward. We will meet you where you are, but I just ask you to please come with us."

At the November PTA meeting, Estrada-Thomas said Johnston is making progress, adding that the staff is looking for ways to make the school more relevant to students. Once students get to school, they have to see a connection between what they're learning and the outside world, she said. "We will make fantastic gains this year, we will," Estrada-Thomas told a group of about 40 parents who attended the dinner meeting. "Things are going great. Everything is in place; we've gotten the help that we need, but we have to continue to push ourselves as educators, and you have to continue to push yourselves in the community."

Yet Johnston's attendance continues to fall, often 8-10% below the state and district average. Students at Johnston often cut class, simply picking and choosing which classes they want to attend during the day. Almost everyone at Johnston talks about the problem and how it's going to have a big impact on test scores.

Estrada-Thomas has asked for volunteers to patrol the campus during lunch. At the nine-week mark in the school year, 57% of Johnston's students already had at least two unexcused post-lunch absences. Attendance figures in the school bulletin the week of Johnston's homecoming noted that overall attendance was going down, rather than up, as the school year progressed. Attendance the first six weeks was just over 85%. The week of Oct. 26 it had fallen to 83%.

The real test for Johnston will be scores on standardized tests in April, but Johnston should already have a sense of how the students will do. Like many schools, Johnston benchmarked its scores at the beginning of the school year and will repeat the process, most likely in December and February, to estimate whether students will be able to hit the mark in April.

Joe Kopec, a retired Austin High principal who acts as one of four members of the state-mandated Campus Intervention Team, praised Estrada-Thomas, saying the campus is doing everything it can to raise student achievement. But Kopec admitted the first set of benchmark scores this fall was a disappointment, lower than what school leaders expected to set the pace to pass the test in April.

Johnston has made some gains. It has an active PTA for the first time in 17 years and a football booster club for the first time in a decade. The booster club, after a successful barbecue fundraiser, hosted a free tailgate party for students and alumni in the parking lot of Nelson Field before the homecoming game, serving up brisket and sausage. "We're making money. Coach is putting together a program. We have a PTA. We're moving ahead," said David Fuentes, who played baseball at Johnston and graduated in 1981. "I was brought up to believe you stick it out until the end. We're going to do everything that we can do, but I think it all comes down to how bad the students want it."

School and district leaders have recited a litany of challenges that face Johnston. One in five girls at the school will bear a child before she graduates. One in three doesn't speak English. About 40% of those students who enter Johnston in any given year won't finish the school year there. And with an average household income of $9,000 in the surrounding neighborhood, many parents expect their teenagers to work. PTA President Geneva Oliva, herself a 1974 alumna, admits that once the money starts rolling in, parents often decide a GED is just as good as a Johnston diploma.

Those are all good reasons why Johnston faces many challenges. But look at the Texas Education Agency website, and pull up the list of Johnston's Campus Comparison Group. That's the list of the 40 campuses in the state that the TEA considers to be most similar to Johnston in demographics.

Many face the same challenges as Johnston but see twice – or even three times – as many students pass the state-mandated tests. The demographics of San Antonio's Brackenridge High School are close to 90% Hispanic and low-income, with a mobility rate of about 30%. Yet the campus sends 70% of its students to college and is the top-ranked Texas high school for sending students to the University of Notre Dame.

Consider Davis High School, in Houston, with demographics similar to Johnston. An oil-company-sponsored college scholarship – which promises a four-year scholarship to any Davis grad with at least a "C" average – means that when compared to similar high schools, Davis students now score in the top quartile in both language arts and math. Forgione says AISD is exploring similar incentives for Johnston – students zoned to the school might be more willing to stay put, he said, if they know a college scholarship waits at the end of four years.

At the October town hall meeting, principal Estrada-Thomas gave parents every assurance that she and her staff were doing everything they could to raise test scores. The majority of teachers, for the first time in a number of years, were returning to the campus instead of requesting transfers. A campus instructional strategy, with content-team leaders, would focus intently on the four core subject areas. And every Wednesday afternoon, Estrada-Thomas and her instructional team would sit down for a three-hour meeting to review student progress. "We call it the Power of Nine," Estrada-Thomas said. "Our No. 1 priority is instruction improvement and supporting our teachers in every way possible."

School officials have added twilight school to recapture credits and Saturday school to improve attendance. They have doubled the time on math and reading offerings. Discipline referrals are down, attendance is up, and block walks with volunteers have reclaimed dropouts and cut the dropout rate in half. Estrada-Thomas told parents in October that the leadership at the school was not just working harder but smarter.

They say it takes three to five years to change a school's culture, Estrada-Thomas told the group. Johnston is in year three, just hitting its stride. With time and encouragement and the presence of parents on campus, this turnaround could work, she said.

"We've got the programs in place," Estrada-Thomas declared. "All we're going to need here is just a little more time." If that's true, then why does the student enrollment continue to erode and the attendance rates fall? And why are so many people saying privately that it's too little and too late?

Just Walking Away

Most would argue that the turning point at Johnston – that point when Johnston went from established to dying – came with AISD's 2002 decision to move the Liberal Arts Academy from Johnston to LBJ. From one year to the next, the enrollment in the band dropped from 90 to 10. The entire award-winning journalism program was wiped out. Worse, from the academic standpoint, enrollment in Advanced Placement courses dropped by half, making it more difficult to field and fill a variety of courses for the remaining college-bound students at Johnston.

At the time, supporters of the LAA move argued that higher-achieving white students actually masked the scores of Johnston's neighborhood students and that the move would force the school to finally address its lagging test scores. (They're now making the same argument about LBJ.) Angry neighborhood parents said the magnet, oversold as a benefit from the start, had failed to bring in the quality instructors and better instruction for the nonmagnet students at Johnston.

Some, like neighborhood pastor Townsend, would argue that Johnston was never intended to be a strong academic campus. As early as 1991, AISD was proposing to close Johnston and replace it with some other program. Townsend, who graduated from LBJ in 1995, remembers that Johnston was always perceived as "the trades high school." All the students, interested or not, were pushed into career and vocational programs, often at the expense of academics. Townsend said the perception at other high schools in the Austin district was that you might go over to Johnston to take a class, but you never wanted to enroll there.

Hector Montenegro spent three years as principal at Johnston in the mid-1990s and was considered the one man who had the best chance of turning the school around. At the time, Montenegro welcomed the opportunity. His wife had graduated from Johnston. He saw the school as a strong blend of magnet and neighborhood students, not a trade high school propped up by the scores of the school's liberal arts academy. "Yes, we had career and technology, but I didn't see that as part of the problem," Montenegro said. "I think the bigger part of the problem, though, was this image that people had of the Dove Springs kids, that they weren't college-bound."

The departure of the magnet was significant, but University of Texas education researcher Ed Fuller would argue that Johnston was on the downslide well before that. The trouble, he says, began back in 1999, when teacher turnover on the Eastside campus spiked above 30%. That should have been a sign to district officials that something significant at Johnston needed to be fixed. "One of the first signs of a problem campus is that the teachers start bailing out," Fuller said. "It's like rats jumping off a ship. No one wants to stay in a bad job. That's true for any profession, and it's especially true in education."

It's a commonplace assumption that teacher experience is a significant indicator for student success. Johnston's faculty – and there is a caveat here that the statistics include the former Liberal Arts Academy faculty – went from a majority being more experienced than most teachers in AISD to a majority having 10 years or less in the classroom and a good percentage being either brand-new teachers or teachers with less than five years' worth of experience.

Parents, even if they couldn't put their finger on it, sensed that the district should have recognized sooner the school's distress, reflected in the turnover. Oliva, the PTA president, had three children who attended Johnston over 10 years. She herself comes from a family of eight children, most of whom attended the school. Asked just what went wrong at Johnston, Oliva talks first about the turnover of both the principals and the faculty. She blames the district for failing to see the problem for what it was.

"I think what's happened at Johnston happened because they weren't keeping up with us. The turnarounds in principals, the turnarounds in teachers. ... They should have realized the problem. It's like they decided they would give up on Johnston," Oliva said. "How can our students continue to learn when you have too many substitutes in the classroom? How can you expect the school to survive when you have so many principals? Now the school board's coming down and blaming the parents, blaming the students? Why let this go on at Johnston for four years before really doing something about it?"

School leaders certainly would argue that they've made substantial changes to improve performance at the campus. They brought in consultants. They visited schools. They decided to divide the school into three, and then two, small learning communities so that students would get personal attention. They brought in the International High School to share the facility, students who have been a significant part of the football and drill teams.

But those moves have not always been the right moves. In community meetings, Forgione has praised the school for making strong gains, especially in literacy. In a letter to then-Commissioner Shirley Neeley in June, though, Forgione admitted the 2005 redesign plan was ill-conceived, and that it needed to be replaced with the school's current curriculum effort, First Things First.

"The redesign plan we initiated at Johnston two years ago, with the Texas High School Redesign and Restructuring Grant, was unfortunately based on the use of individual best practices and not a cohesive, research-based model," Forgione wrote. "While it was implemented with great commitment and effort and in concert with a reconstitution of most of the school's teaching corps and leadership, it did not represent the kind of comprehensive, cohesive, best-practice model that First Things First provides.

"Our lack of experience with the principles of effective high school redesign at the campus and district levels at that time was partially to blame for the mistakes made in this design. We have learned a great deal over the past two years from our work with TEA, the Texas High School Project, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, IRRE [Institute for Research and Reform in Education] and our other redesign partners. We now understand that the implementation of the proven FTF model with fidelity through a close partnership with IRRE offers the best opportunity for turning Johnston around and serving the students of Johnston well."

And the International High School? While the non-English-speaking students have done relatively well in an intensive limited-English group setting, Townsend is unimpressed. "They knew the school was in trouble," he said. "Why did they go ahead and bring in students who were going to have difficulties? I don't know why they didn't bring in something that was going to help Johnston be successful."

Teacher turnover and the wrong academic model are two direct factors that impacted Johnston. Those factors, however, combine with two other district trends that Fuller says have impacted Johnston indirectly. First, through much of the Nineties, AISD – in a well-meaning attempt at greater faculty diversity – delayed hiring teachers until every qualified minority applicant possible was sought and reviewed. What does that have to do with Johnston? It means the district, when it failed to hire those quality minority applicants, returned to its original applicant pool. The district ended up hiring for Johnston in the first and second weeks of August and typically hiring the weakest applicants. Remember being the last one picked for dodgeball? It applies to hiring teachers, too.

And where do these teachers end up? They end up staying in AISD, and they tend to gravitate to the schools with fewer demands, Fuller said. Those circumstances tend to suggest that not only are there too many teachers who are new at Johnston but that some of the more experienced educators are probably not of the highest caliber, Fuller said. "I lay the blame with the school district," he said. "The district should have caught this sooner. They should have recognized it as a sign and fixed the school."

Forgione rejects Fuller's charge, saying the real challenge in Austin is not recruiting teachers; it's retaining them. Twenty years ago, Austin had its pick of teachers. These days, it has to compete with fast-growing communities like Del Valle, Manor, and Round Rock.

The second factor, which few people want to acknowledge publicly, is that Austin traditionally has had a weak principal corps. For whatever reason, most AISD principals have lacked longevity, and some have lacked quality. Johnston may be the worst – with 10 principals in eight years, including the infamous and arrested Al Mindiz-Melton – but almost every high school in the district has suffered from regular principal turnover.

Teacher turnover is one statistic. Principal quality is another. Now consider a third statistic concerning Johnston. On the aforementioned Campus Comparison Group report is a column listing a number indicating how many students are being compared. To be fair, the state will only compare students who were on the campus the year before. So a comparison of similar campuses in 2006 would look only at those students who were enrolled in the comparison school in both 2005 and 2006.

Brackenridge could find 1,021 students to match, year-to-year, on its 1,800-student campus. Davis had 821. Johnston could find only 281 students. Students are, literally, walking away in droves from Johnston and never returning.

Then consider the impact of these three combined factors: Principals aren't there long enough to weed out bad teachers, teachers aren't around long enough to know their students, and students have no knowledge of either. All of these can easily lead to – or be exacerbated by – the chronic attendance issues at Johnston.

Under those circumstances, it's not surprising to see students, along with parents, jumping ship. As you walk down the long main hall of Johnston, you can see it in the senior class photographs. Johnston was never large. It never graduated more than 270 students. But as you follow the line of pictures down the hall, right through the late Nineties, you can see the class size slowly shrinking. And those principals on the front row – the same, reassuring group of four through much of the Nineties – become a troubled sea of changing faces. Estrada-Thomas, with three years at Johnston, now qualifies as a seasoned administrator.

As it is, students at Johnston tend to desert the campus or pick and choose which classes to attend or simply leave at lunchtime and never come back to school. At a recent PTA meeting, Estrada-Thomas told parents that better than half the students had two or more absences from post-lunch classes, but when it was suggested the campus should be closed for lunch, there was a flurry of protests from parents. In the end, Estrada-Thomas decided she didn't want to punish the seniors. And the number of absences and tardies on campus – recorded dutifully on the weekly school bulletin – continues to rise.

Eastside Pride

Community members often consider AISD to be more of a hindrance than a help in trying to rescue flailing schools. Historically, Superintendent Forgione has advocated closure and reuse of a campus rather than early intervention, as with his proposal last year to reuse the now-resurrected Webb Middle School as the district's all-boys school. And it's not just Forgione. As early as 1991, the district had proposed closing Lanier and Johnston campuses and using them for alternative schools.

State law doesn't always favor fixing the school community's problems, either. If Johnston fails this year, the campus could be turned over to a nonprofit for operation. Some in the community are speculating that Southwest Key – which failed to get one of the handful of remaining state charters this year but still appears to be hovering in the wings – is simply waiting for the school to fail in order to secure the campus.

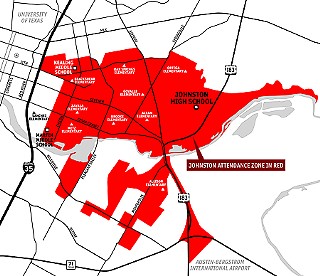

Johnston parents often put the lack of advocacy on behalf of Johnston on the school's feeder patterns and the district's open transfer policies. Johnston's attendance boundaries are drawn for a high school of 1,375 students, but only 657 attend. More than 600 choose to go somewhere else.

The problem starts in middle school. The elementary schools in Johnston's feeder pattern (see map) attend either Martin or Kealing middle schools. Johnston parents complain that parents – particularly mobile, middle-class parents – choose to send their children to Austin High School. The district's transfer policies, echoed by the federal No Child Left Behind law (which requires open transfers from underperforming schools), have indirectly resegregated Johnston for only the poorest children.

"We have students who live across the street from Johnston who catch a bus to go to Austin High," said Fuentes, with a shake of his head, as he tends to the smoker at the tailgate party. "That just makes it rougher on us. The smaller the group of students, the more every student counts. It puts a lot of pressure on the kids."

Most speculate – and some say AISD has run the data – that most of the brighter Johnston-zoned students now go to other high schools. Ironically, that means that the pride of the Eastside is, in all likelihood, over at Austin High.

Gabby Camarillo is one of Johnston's overachievers. Likable and outgoing, Camarillo looks and acts like a student leader on any high school campus in Austin. Not only is she the co-captain of the cheerleading squad and secretary of the student council; she's also the president of the senior class and captain of the school's softball team. And, like her mother, Camarillo maintains strong ties to her community. Her kindergarten teacher sat alongside Gabby's mother at the Johnston homecoming game.

Gabby's older sister graduated from Austin High School. Her older brother graduated from Anderson. Gabby, a senior, chose to attend Martin Middle School and Johnston High, even though she estimates no more than 20 of her classmates from her early years of school actually ended up graduating from Johnston.

"I wanted to come to Johnston. I'd heard good things about it," Camarillo said. "It's a small school, and I think you get a lot more one-on-one attention here."

Pride of the Eastside struggles to survive state mandates

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.