Left Behind

AISD moves to close Webb Middle School – and to transfer the 'merchandise'

By Michael May, Fri., Feb. 16, 2007

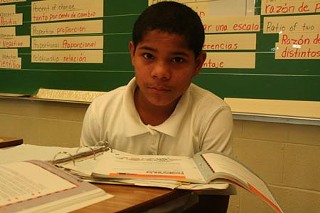

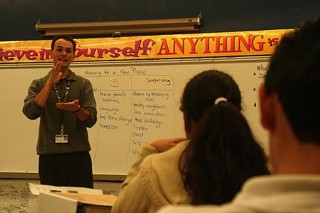

It's third period at Webb Middle School, and seventh-grade English teacher Patrick Harboure is at the blackboard, listing everything that's different between the United States and the home countries of his students, who are all recent immigrants enrolled in the English Language Learners Academy, or ELLA. Harboure is an Argentine and, like most of his students, a native Spanish speaker. But when he's in front of this class, he speaks in steady, enunciated English, with only the slightest accent. Meanwhile, his students grope for words, mutter Spanish under their breaths, and giggle with embarrassment when called upon. Still, the students slowly add to the list on the blackboard: The language is different here; the schools have computers; you have to pump your own gas. He asks the class if there are any laws that are different in the United States and calls on one of the students, Mañuel.

"Here, if you don't come to school," Mañuel pauses, and the class starts to giggle. "Ayyy. Que es eso?" He rests his head on his arm.

"The exact word doesn't matter," says Harboure, a mix of encouragement and irritation in his voice. "Explain the law to me."

"If you don't come to school," Mañuel begins again, "it has a law you have to have an excuse to bring to school that is the cause that you didn't come to school."

It's the closest thing to a full sentence I've heard from a student in nearly 15 minutes. Harboure is pleased. "So, if you don't come to school, you need an excuse," he reiterates. "In Argentina, if you don't come to school, nobody cares." The class laughs uproariously at this assessment. "Is it like that in Mexico? Honduras? Cuba?" Yes, the students nod in agreement. Before they came to the United States, these students had never heard of parents being tracked down and fined when their children don't show up for school.

Moving the Target

In the past few weeks, Webb students have learned of another unforgiving state law: If more of them don't pass the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills test – in English – by the end of this school year, then Webb will be rated "low performing" for the fourth year in a row, and the Texas Education Agency could decide to close the school or have a private company or other district take over the management.

Webb is one of only five schools in Texas that have failed the standards for three years in a row. But there are another 38 schools that have missed two years, and, as the state's standards get tougher, many more will surely follow. Webb is a test case, and its current predicament illustrates a dark irony that reverberates downward from the District of Columbia through Austin and back again. The state's accountability system, designed (in theory) to ensure the highest standards in all schools, paradoxically appears in practice to be punishing the very students it was most designed to help.

The Texas system, which became the model for the federal No Child Left Behind Act and program, is based on the concept that all schools and all students should be held to the same standards. It's a noble goal – why shouldn't a school in West Lake Hills be held to the same standards as a school in East Austin? (Always allowing for the impolite but open secret that the academic and community resources in West Lake and East Austin are hardly comparable.) The designers of the TAKS test now cleverly parse out ("disaggregate") the data at each school according to ethnic and economic groups in order to make sure that teachers cannot simply lavish attention on the students most likely to pass the test and thereby derive a high average score unreflective of student inequities. Under state and federal standards, a school is deemed low-performing if any one subgroup fails to meet state standards, whether it consists of African-American, Hispanic, or economically disadvantaged students. The five schools in Texas that have been rated low-performing for three years in a row are all in urban areas.

"This doesn't mean that these are the worst schools," says TEA spokeswoman Debbie Ratcliffe. "Rural schools tend to be more homogenous and are often rated on just one group. Urban schools have more diversity. If you have over 30 students in one ethnic group, you will be rated separately in that category. That means urban schools do have more hurdles to cross."

And the state raises those hurdles every year. It's not enough that Webb has improved in most categories each year; the TAKS bar has continued to rise out of reach. Webb is a typical inner-city school, which means it has students in every category taking several tests, which leaves the school with 26 separate ways to fail (see chart below).

• In 2004, the students at Webb actually met the standards on the TAKS test – but then the state decided that students who didn't make it to high school were to be reported as middle-school dropouts, and several Webb students hadn't shown up for ninth grade. Because of that subgroup, the state rated the whole school low-performing.

• In 2005, the school's African-American and economically disadvantaged students did not meet the standards for reading, and African-American students also fell below the math standard.

• In 2006, Webb's African-American students showed dramatic improvement on the TAKS test. But the student body as a whole, as well as Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students, failed to meet standards on reading and social studies.

The tests certainly identify a school's problem areas, but a closer look reveals that the Legislature's mandated solution – closing the school – is more of a whip than a salve.

Out the Window

Ruben Alvarado has been working at Webb since it opened 15 years ago, and he's now the director of ELLA. He's watched the school change from a mixture of African-American and English-speaking Hispanic students to a population that is largely recent immigrants or the native-born children of immigrants. The Austin Independent School District opened ELLA seven years ago, and it now includes about 120 immigrant students who have recently arrived in the U.S. It's challenging to teach these kids English and simultaneously make certain they don't fall behind their peers. Yet Alvarado is not at all fatalistic about these children's future. "You'd be surprised," he says. "These students do catch on fast."

The problem is they aren't catching on nearly fast enough to meet state standards. The TEA used to allow students with limited English to be exempted from the test for several years, but under pressure from the federal No Child Left Behind system, the state has changed the rules. Now students who have been at school at least a year must take the tests in English, regardless of how well they speak the language. Yet educators say it takes most people at least seven years to become fluent. "We adults couldn't do what the state is asking," says Alvarado. "There are university students that come here and take intensive English courses for a year and then fail their English-proficiency exams. So it's hard to expect these kids to do that." Alvarado says about 30% of the ELLA students that took the English reading test passed, which is "pretty good," considering they've been in the country less than three years.

The students in the ELLA program get some of the most intensive language preparation in the district, so it's hard for them to understand how closing the school could somehow be to their advantage. Darwin Rios, a keen-eyed 13-year-old who arrived from Honduras about six months ago, is already confident enough to read English word problems in front of his math class – even if he doesn't understand all the words. He lives very close to Webb and worries about his future if the school closes. "It's not fair that they're thinking of closing the school," he says in Spanish. "Here I have teachers that I like. Here I have goals. I'm just getting used to things here; I don't want to have to start over at another school. I think I'll have a better future at Webb."

Rios takes advantage of Webb's Saturday tutoring, which helps students prepare for the TAKS test, but Alvarado says many students don't have the time. "A lot of our students' parents are working two or three jobs and expect these kids to take care of their younger siblings after work," he says. "I feel sorry for these students, but I also have to impress upon them that they must improve at school and pass the test, and we are here to help them do that. Still, it's tough. If they're not here, we can't help them."

The 120 students in ELLA get intensive help learning English, as well as in the TAKS-test content areas. The program is provided to students who have just arrived from another country – but, unfortunately, these are not the only students at Webb struggling to learn English. In fact, nearly half the students at the school have limited English, and most of those students are not getting any remedial language classes.

It may be startling to learn that many middle-school students who've been attending Austin schools since prekindergarten are still unable to take a test in English. The bilingual programs at Austin's elementary schools are designed to give immigrant students English skills while instructing them in content areas like math, science, and social studies. But the state's accountability system, unaccountably, has given elementary schools a perverse incentive to keep children learning in Spanish – it gives elementary students the option of taking the test in Spanish.

I first met fifth-grade bilingual teacher Stacey Smith in 2003, when I was reporting a story about Pickle Elementary, a feeder school for Webb that had just opened in a beautiful new facility in the St. Johns neighborhood. The school hadn't had a chance to fail any TAKS tests yet, and Smith was enthusiastic about the potential of the school staff to help these struggling immigrant students and the neighborhood as a whole. In the years since, Pickle has struggled to meet state standards, and every time I've seen Smith, she seems more despondent. She finally had to take a break this year, largely because of the pressure of the testing system.

"It's just demoralizing," she says. "At the beginning of the year, I have a plan about how I'm going to work English lessons into all my instruction, to make sure these kids are learning the language as well as the content. And then, in November of every year, we have the kids take their benchmark TAKS test, and when the results come back, everyone freaks out. You go into emergency mode. You think, 'OK, these kids are taking the test in Spanish, so they need more instruction in Spanish.' And everything I'd planned all summer goes out the window – again."

The strategy does allow the school to meet state standards – Pickle Elementary was rated "academically acceptable" last year – but it sets the students up for failure when they reach middle school and have to take the TAKS test in English. "It's like everybody wants everything all at once," says Smith. "It is theoretically possible to teach kids both English and content simultaneously, but it takes time and a lot of support. We have yet to see what's successful in the TAKS world we live in."

The problems facing Webb, and all three of the current Northeast Austin middle schools, can seem overwhelming, so it's important to note that many of the students are succeeding. Webb eighth-grader Celia Gutierrez is being raised by her two older brothers, both in their 20s, after their mother died. She says she's passed the TAKS test, but it hasn't been easy. She credits the support she's gotten from her favorite teacher and says that students just need someone they can turn to for help. "That's what I needed," she says. "I found it, and my grades improved."

Running the Numbers

In January, AISD Superintendent Pat Forgione called a community meeting at Webb to announce that he planned to close the school at the end of the year. Hundreds of parents packed the Webb cafeteria, many wearing headphones providing a simultaneous Spanish translation of the superintendent's speech. Forgione argued that shutting down the school would be in the students' best interest, since the state could decide to close the school in June and leave the district scrambling to find spots for students and teachers. "We just don't have the resources to serve these students at Webb," said Forgione. "We have kids coming into sixth grade that are testing at a second-grade level." The superintendent proposed the district take proactive action and move the students to Pearce and Dobie middle schools – both schools that are also rated low-performing by the state.

The parents of Webb students didn't see how that plan was going to help their children learn, never mind that it seemed a sure way to make certain that Dobie and Pearce would be in the same predicament in a year or two. The meeting lasted until almost 11pm, with a seemingly endless succession of parents, teachers, and students demanding that the district keep their neighborhood school open. Ilene Jones, a recent Louisiana transplant and the mother of a Webb eighth-grader, set the rhetorical tone early in the night. She seemed to channel a lifetime of anger at the public schools directly at Forgione, with a cafeteria-quaking sermon that accused the superintendent of ulterior motives and bureaucratic indifference. "You want to bus our children to other schools as if they were merchandise," said Jones. "Our children are not merchandise!"

In the week following the meeting, a group of neighborhood activists from the St. Johns neighborhood began to meet and organize an official response. Alan Weeks, vice president of the St. Johns Neighborhood Association, summed up the neighbors' perspective. "The accountability system was meant to force the district to improve the school," says Weeks. "Fire the entire staff. Cherry-pick the best teachers, and bring them in. It's a strategy that makes some sense. But kicking students out of their neighborhood school? That's purely punitive. It makes no sense."

The parents and neighbors seemed to share a pervasive sentiment that there was more behind the decision than test scores. They were right. The district had raised $35.8 million dollars in the 2004 bond package to build Garcia Middle School, a state-of-the-art facility in far Northeast Austin designed to hold 1,100 students. The problem with the plan is that the school is due to open next year – and the expected numbers of students aren't enrolling there. If AISD keeps Webb open, they will have four middle schools in Northeast Austin operating under capacity, which is not only expensive for the district but makes it difficult to offer the full range of extracurricular activities in those schools.

Paul Turner, director of facilities for AISD, says the district's projections were off by approximately 290 kids – not enough to force the district to close a school. But the district did not anticipate the number of students that would transfer out of the Northeast middle schools by choice – 211 at Dobie and 275 at Pearce. "No Child Left Behind allows students to transfer out of schools that aren't meeting the standards," he says. "And the district also has a very open enrollment system. The end result is that Dobie and Pearce have each lost students to other schools in the districts where parents feel more comfortable. It's kind of depressing when you look at the number of students leaving those schools." In other words, the feds and the district have allowed students – likely the strongest students – to leave struggling schools, leaving those campuses that are much likelier to fail.

Forgione has another reason for closing Webb as a middle school – it would leave the district with an empty building. Forgione says he'd like to open a young men's leadership academy at Webb, to complement the district's Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders, which will open in Porter Middle School next year. "We have to look forward to the next 50 years of this district," Forgione said. "We can utilize Webb to create a jewel in this district, something new and beautiful. The state's data shows us that the high school test scores for African-American and Hispanic boys are lagging 5 to 10 percent behind the girls' scores. We need to get ahead of the curve."

The plan is almost identical to what the district has done with Porter – close a failing, underenrolled campus and turn it into a specialty school. But there's one significant difference. The Porter community, comparatively speaking, accepted its fate with resignation, while the St. Johns neighborhood is putting up one hell of a fight. AISD board of trustees President Mark Williams came to both public meetings at Webb, and the experience left an impression. "It made me realize that we have to decide what is in the best interests of the students," he said. "Not just what is in the perceived best interest of the district. I feel bad that we are making a decision that may not be good for these kids and could also hurt kids at other schools."

But Williams doesn't see an obvious solution to the low test scores at Webb. Schools with Spanish-speaking populations have succeeded in the Valley but with a much more homogenous population and a wealth of bilingual teachers. "We may have to start looking at something entirely different," he says. "We're now held accountable, but the country hasn't changed the education model for 50 years. We need to understand that different kids are in very different circumstances. For instance, many of these kids don't have parents at home to help with homework. They need a lot more attention. We could try elongating the school day, but then you face the transportation issue – all of our buses are rotated on a specific schedule between all of our schools. And you might have parents saying it's unfair that my child has to stay later. And where would the district get the resources? If you put more resources into Webb, they have to be pulled out of somewhere else."

A major transformation is not on the horizon. After the public forums, Forgione reacted by tweaking his proposal. He is currently suggesting the district wait until May 2008 to close Webb, although incoming sixth-graders would start instead at Dobie and Pearce next year. He's also recommending a host of changes at those campuses, such as creating sixth-grade clusters to ease the transition and instituting a summer school to help the students catch up. (See "Forgione's BEST-Laid Plan," p.32.) It's an acknowledgement of the enormity of the problem, but it's hard to imagine that it will be enough. The federal accountability system expects 100% of the students to pass the test by 2014, and the state is steadily raising the TAKS standards by 5 to 10% a year – no matter if the student's parents work at Dell or recently swam across the Rio Grande with a backpack and a gallon of water. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.