Troublemaker

My contribution to Willie Nelson's 'Complete Atlantic Sessions'

By Ed Ward, Fri., Dec. 29, 2006

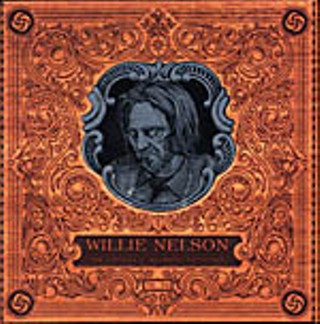

In June, Rhino Records issued a 3-CD box set called Willie Nelson, The Complete Atlantic Sessions. As always with such collections, there were extended versions of the issued albums. Not as always, I was anxious to hear them, at least the ones for 1973's Shotgun Willie. After all, I'd been there when they were recorded.

I first became aware of Willie Nelson at Rolling Stone in 1970. One of my fellow editors, John Morthland, was checking out a small stack of albums RCA had sent him. The covers showed a geeky-looking guy without much of a chin and with a bad haircut, profoundly ill-at-ease with being photographed from the looks of things.

"He's going to be playing the San Francisco Folk Festival," Morthland told me. I admitted I'd never heard of him. "Songwriter from Nashville. He wrote the Patsy Cline hit 'Crazy.' Wonder if we'd want a story on him."

Apparently not; that was the last I heard of it.

Over the next couple of years, an old college friend's band, Asleep at the Wheel, moved to the Bay area and helped educate Morthland, myself, and a lot of our friends about country music. In late 1972, Willie's The Words Don't Fit the Picture became one of my favorites. It was depressing as hell, but the unusual melodies cushioning his equally strange chord progressions were haunting, as were the doom-laden lyrics. The cover of the LP showed a ragtag group of hippies, and one stately blonde, getting into a limo. One of the hippies was the chinless guy from the RCA albums, now grown into his face. Soon I'd meet them all, including the blonde, Willie's wife Connie.

After getting fired from Rolling Stone in October 1970, I'd begun writing for Creem, the irreverent Detroit-based magazine. Creem's business manager was a Connecticut-based gruff in the Allen Klein mode, Neil Reshen, who did accounting and managed three artists: Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Miles Davis. "We manage the unmanageable" was his motto. At one point, he'd paid to have his open-heart surgery videotaped, a very expensive proposition at the time, "to prove," he claimed, "that I have a fuckin' heart."

At this point in his career, Willie had made his celebrated move back to Texas and was in the process of bringing Austin's rednecks and hippies together, playing everywhere from car dealerships on Sixth Street to the fabled psychedelic dungeon called Armadillo World Headquarters. While the world at large wasn't tuned into this, some of its hipper denizens were, and among these was Atlantic Records' Jerry Wexler, who'd decided it was time for his label to gently test the waters of country music, especially when he found out Willie's contract with RCA was up and Reshen was seeking more salubrious waters for his client's talents. On a visit to Nashville, Wexler heard Willie perform the group of songs that became Phases and Stages during a late-night guitar pull at Harlan Howard's house. He was smitten.

Paper flew between Texas, Connecticut, and New York City. Ink was applied to some of it; more paper ensued, more ink, and then the papers of financial nature were finalized. Willie Nelson was an Atlantic Records recording artist. A session was scheduled for early 1973 at the label's fabled recording studios near Columbus Circle in Manhattan, and staff producer/arranger Arif Mardin, not Wexler himself, was put in charge.

This historic session had to be documented, all agreed, so Reshen called Creem Publisher Barry Kramer, who said he'd be delighted to run a big story. Now who among the merry crew in Detroit could cover country music? Indeed, who didn't outright hate the stuff? Ah, the guy in California!

The studio had been reserved for five days since Willie was known for cutting quickly, and I was in a froth of anticipation: I'd be in New York, so I could see friends; I'd have an exclusive story on an album that would very likely be of the same high quality as Wexler's last foray into Texas music, Doug Sahm and Band. Hadn't Dylan himself shown up for that one? Maybe Dylan would show up for this one, too! I'd also be in Atlantic's historic studios, where so much of the music I'd loved and so many of the great musicians and producers – not the least of which was Wexler himself, whom I'd hung out with on occasion in San Francisco – had recorded.

It was at that point that I did something so incredibly insensitive and stupid that every time I think of it, even 33 years later, I wince. Another of my Rolling Stone colleages, John Lombardi, had been married to a lovely woman from Philly named Wendy. They'd gone through a painful divorce, and she'd moved to New York to further her career as a photographer. She was good, but she wasn't getting much work. I got her number, called, and asked if she'd like to shoot the Willie sessions for Creem. Of course she said yes.

I flew to New York, checked into a West Side Howard Johnson where the band and crew were staying, and then made my way to the Atlantic offices. After a bit of protocol, I was sent upstairs to the studio where I was met by Reshen, whose first utterance was, as I remember it, "This is going to be a positive story, right," not even phrased as a question. He then announced I was the journalist. The journalist!

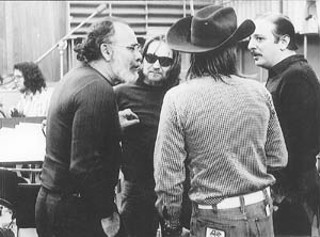

A lot of hand-shaking went on. I met Mardin, a short, energetic guy, all business, but with a twinkle in his eye that indicated some of the business was filed under "monkey." Then there was the band, the one Willie used on the road. There was Willie; his shadow Paul English, who played drums; Bee Spears, a tall, lanky bass player who acted like the dumbest hillbilly on the planet to cover up his basic shyness; Willie's sister Bobbie, with an incredible mane of long hair descending straight down her back like a brunette waterfall; and the musician I was interested in the most, steel guitarist Jimmy Day, whom Asleep at the Wheel's steel player Lucky Oceans had told me to watch closely. At that point, I owned an astonishing double-eight-string National steel guitar I'd bought for a pittance in a Cincinnati pawnshop, so I was hot on steel styles, even pedal steel, which my instrument wasn't. It was stolen from my house a couple of years later and showed up a week after that during a jam at L.A.'s Roxy, in the hands of an Eagle who shall remain unnamed but who threatened to have me beaten senseless if I pushed my inquiries as to where he'd gotten it.

Willie & Co. began setting up, and the whole boring affair of checking snare sounds and so on took most of the rest of the day. I'd forgotten one crucial fact when taking the assignment: Recording sessions are incredibly tedious for those not actually engaged in them. It wasn't like I'd never been to one before, but suddenly I realized I'd signed up for the duration. Damn, hope Dylan shows up.

Happily, I'd underestimated the professionalism of all concerned, not to mention the core ensemble of musicians themselves, who decided to test the sound of the studio with a spirited version of "Under the Double Eagle," which left me awestruck: Willie wasn't only a great songwriter, he was a goddamn virtuoso on that battered Martin guitar of his! After a couple of takes, the crew called it a day, and we all trooped into the control booth to hear what had transpired. "That might be a keeper," Mardin nodded with a smile.

The next morning we all showed up again, and as Willie and Mardin went over some possible songs to record, Wendy Lombardi showed up. I pointed out to her who was who, cautioned her to stay out of the way (like I actually needed to do that), and she began assembling several cameras. At that point, the studio door opened, and a short man, similarly bedecked with cameras, walked in.

"Who," he asked Wendy, "are you?"

She explained that Creem – here pointing at me – had asked her to cover the sessions. The guy walked over to me and stuck out his hand. "David Gahr," said the legendary Village Voice photographer who'd documented the New York underground for two decades. "I don't know who you are, or what your magazine is, but I do know that Jerry Wexler employs me on behalf of Atlantic to cover recording sessions here and that he personally invited me today to shoot this for the media. I'm trying to make a living, I have a relationship with this company, and I don't appreciate strangers being invited to compete with me. I'm happy to sell your magazine some photos, but I can't allow another photographer here. You can ask Jerry. He'll tell you."

I could feel my face burning with embarrassment and apologized. I told Wendy she had to leave and why. She looked at me with contempt.

"I would've thought you'd bothered to work this out beforehand," she snapped, disassembling her cameras and stomping out.

Things could only go uphill from here, and they did. The band recorded a bunch of tunes that first day. I remember being very excited by "Sad Songs and Waltzes," which was first-rate and nailed in a couple of takes. During overdubs and tracking of individual parts, there was lots of time to talk to Willie and other band members, and I got most of my story that first day.

Now I should warn you that I may not have my chronology strictly correct here, nor have I seen my Creem story in years and years, but I think it was the next day when we started getting visitors, one of whom was the irrepressible Doug Sahm. Willie wanted to record a Western swing number, with the encouragement of Wexler, who was evidently involved in another project at the time but would drop by to see how things were progressing. Sahm had brought along some of his Texas cronies, including Augie Meyers, drummer George Rains, and fiddler J.R. Chatwell, who told me he was 80 (I think he was just playing with my head) and thus became the oldest person I'd ever smoked pot with.

"My doctor told me drinking would kill me," explained Chatwell, "and I told him I liked my beer. 'Well, J.R.,' he said, 'I can't tell you what to do, but down where the Mexicans live ...'"

An arrangement was needed for "Bubbles in My Beer," and Mardin, Wexler, Willie, and Sahm talked about it while Gahr took pictures. Finally, they got it figured out, and Willie excused Bobbie for the afternoon. "You don't need piano on this?" Connie asked. "Well, then, your sis and I are going shopping!"

"I damn sure better cut a hit," Willie muttered.

It took a while, but eventually the song took shape, and after they'd nailed it, more guests arrived, including a couple of star backup vocalists: Larry Gatlin and Dee Moeller. Another was a skinny Jewish kid with what seemed like dozens of guitars, David Bromberg. My main memory of Bromberg is his unpacking, setting up, and polishing each and every instrument with a fetishlike frenzy. His prize was a vintage National resonator guitar with an etching of a naked Hawaiian lass surfing beneath Diamond Head. He handed it to me to admire, then took it back and polished it again. I realized I'd met him years ago when he'd answered a letter I'd had in Sing Out! magazine looking for other people in my part of the world interested in folk music. He'd driven all the way over from Dobbs Ferry, where his father was an important doctor, he informed me. He was appalled at how bad I was and only stayed a few minutes, long enough to unpack his three instruments and polish them.

By the end of the afternoon, it was clear that there was already more material in the can than could be used. There were also two more days in the studio, so everyone was anxious to keep going and get as much as they could out of the recording. I'm not sure what happened the next day, because I wasn't there.

Actually, I was, in the morning. Things weren't going too smoothly. A few songs were tried, but somehow nobody was getting into the groove. Finally, Mardin said, "I know, let's all go to lunch." We all gathered in the control room and he asked, "Where should we go with these Texans?" I knew a good Cuban-Chinese place around the corner, and he brightened at the suggestion.

The mood improved markedly thanks to the meal, and everyone seemed eager to get back to work as we piled into the elevator back at the studio. At this point, a tall, skinny woman with a barely controlled explosion of red hair atop her head dashed into the building instructing us to "Hold the elevator!" We squeezed her in, and she looked at the assembled crew.

"Arif, who are these people?"

"These guys are the Willie Nelson band," he explained, "and this is our journalist."

She stared at me, and I recognized Carla Bley, co-perpetrator of one of my favorite musical projects of all time, a "chronotransduction" called Escalator Over the Hill, which my college roommate had helped engineer. My heart gave a thump. "Arif, I'm going to borrow your journalist for a while," she said.

As the band got off the elevator at the studio, Willie waved goodbye and half-sang, "Hope we see you tomorrow!" My companion and I went up another couple of floors to the Jazz Composers' Orchestra Association and the New Music Distribution Service, which shared both offices and Carla Bley. Apparently she'd read something I'd written on Escalator and had been impressed, so now she wanted to talk about weird music, which she made, and how to sell it, which is what the NMDS was about. We talked until it got dark, and along the way, I met a guy with a guitar covered in all kinds of junk (Henry Kaiser, I now realize) and an intense fellow who saw Carla giving me records and insisted I take one of his since she was handing me others on the same label, Chatham Square. They were by a composer named Philip Glass, and this guy, Jon Gibson, played in the Philip Glass Ensemble.

The stack of records she gave me turned out to be absolutely life-changing. There was jazz by Noah Howard and Anthony Braxton; Glass' revolutionary classical work; a stack of vinyl by some German guy named Manfred Eicher, whose label, Edition of Contemporary Music, had signed a number of astonishing musicians I'd never heard of, including Terje Rypdal, Keith Jarrett, and Eberhard Weber. There was more, but no way to play it until I got back to California.

Which was where I was going in 48 hours, I realized the next morning. I staggered into the studio, and Bee Spears greeted me with put-on consternation: "Oh, we're so glad to see you. We were afraid we'd never see you again. You got any broken bones?" I told him all we'd done was talk and got a withering look in return. Willie was sitting alone, paging through a little book. A stack of them sat in a box next to him, and if I'd been Southern born, I'd have recognized them immediately as one of the more popular hymnals used in Baptist churches.

"Willie says he's going to cut a whole album today," Mardin said. "He's picking out the material now."

Sure enough, before long, he was handing out hymnals to the band, and one after another, they were recording them. Finally, Willie announced that he wanted a "large untrained chorus" to sing along on two of the hymns, "Shall We Gather at the River" and, I think, "Will the Circle Be Unbroken."

"Everyone in the studio!" he announced.

Not me, I thought.

"You, too, Ed!" he laughed.

We all gathered in a circle under a single microphone. I'm an enthusiastic, if not particularly skilled, singer, but the reason I remember "Shall We Gather" is that I'd never heard the song before, unlike many of the ones he recorded that last afternoon, and I couldn't find a harmony line that made any sense. Everyone else – the band members, Connie, etc. – knew the song, of course. Quite an ending to my week, no doubt about it.

I went back to San Francisco, wrote my article, and waited for the album to come out. When it did, I was surprised, and not entirely positively. For one, it featured as the title cut a song I'd never heard called "Shotgun Willie," which seemed trivial. Clearly there had been more sessions during the weekend, and I was peeved to see that Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter had paid a visit, which I'd missed. I wondered if Atlantic had completely misread Willie.

My questions were answered fairly quickly when Phases and Stages, clearly a great album, came out in 1974. Still, I wondered what had happened to the hymns and had to wait a couple of years until Willie had left Atlantic and signed with Columbia. Sometime after the success of Red Headed Stranger, an album called The Troublemaker came out, produced by Mardin but on Columbia. And even later, chatting with Willie backstage at a gig, I asked him if my vocals had really been in the chorus on that album.

"Oh, you're there, Ed," he said with a glint in his eye. "But we mixed you way, way down." ![]()