Looking for Cheap Dirt

Advocates dig deep and wide in hunt for affordable housing

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., May 12, 2006

Dirt. It ruins your whites. It mucks up your car. You can't eat it. You can't wear it. Around here, you can't even grow much in it, not without being a shameless water hog. But as the old saying goes, they're not making any more of it – and that's why local discussions of affordable housing so quickly turn dirty.

Not that there's any disagreement that Austin is having an affordability crisis. City Council candidates trip over one another to proclaim their love for affordability. It's the new buzzword that affirms your liberal credentials. At a recent forum exploring downtown affordability, the community was unanimous that affordable housing is a good, good thing and we need more of it.

It's when you get to "how" that things get dirty.

At the simplest level, there are way more needs than there is money: Housing Works, a local affordability coalition, estimates that it would take $1.3 billion to ensure that everyone in Austin has an affordable place to live. (The number is an extrapolation from a 2000 HUD study that found 54,000 Austinites paying more than 30% of their income on housing.) But in trying to decide how to meet even a fraction of those needs, things quickly get complicated. Should the city prioritize owner-occupied houses, which can be abruptly flipped for high profits? Rental units, which are permanently affordable but don't help residents build much wealth? How important is it to provide affordable units in expensive central neighborhoods, when the same investment could serve more people on the urban fringe? "How do you balance these sometimes competing goals that you have? You can't always do one and the other. Or sometimes if you do one, it hurts the other," says Frank Fernandez, director of the Community Partnership for the Homeless, who also helped put together the $67.5 million housing bond proposal – one part of the estimated $500 million in overall city needs – that council will review in the coming weeks.

The following proposals involve different ownership structures, housing styles, and funding methods. But beneath it all, both literally and figuratively, is the dirt, and how many people can live on the few square miles of caliche and clay we call Austin.

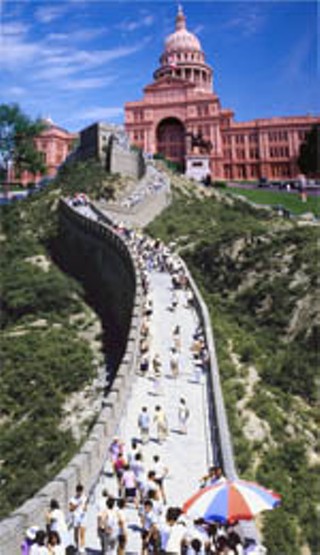

Solution No. 1: Build a Wall

Pros: Also effective in warding off Mongol hordes. In a few centuries, will attract countless tourism dollars.

Cons: Melodramatic rock bands may write bloated anthems about it.

Austin is a good place to live and attracts many who want to make Central Texas home. Too many, perhaps: Over the next decades, demographers predict Austin will swell like a Delta Chi after four years of keggers, popping the 1 million mark (within city boundaries) by about 2020.

Plenty of those folks will be perfectly happy in a production-built landscape of three-side-masonry and tasteful uniformity. Many, however, would rather subsist on yak butter and locusts than live in the suburbs, no matter the price. Therein lies the problem, for central city homes are a very limited resource: In 78704, for example, census data shows only about 6,000 owner-occupied homes, meaning that if housing stock remains unchanged, some 990,000 of those prospective million Austinites can't buy houses there. In case you haven't been paying attention to the last few thousand years of human existence, when scarce supply meets increasing demand, the results are not pretty. If you do not like this dynamic, I would urge you to stick it to the yuppies by selling your central-city home right now, significantly below market, to a certain alternative-weekly journalist.

Or, we can reduce demand the old-fashioned way: Build a wall. A very Austin wall, with murals of Bevo and Stevie Ray on the side, and maybe some restored blackland prairie atop. When children born in Austin reach the age of 18 and want a place of their own, they could be deposited outside the wall to queue up until someone dies. Republicans, of course, go to the back of the line. It's simple, really: Reduce demand, and we don't have to think about increasing supply. So think big. Think wall. Think big, big wall.

Solution No. 2: Build a Shack in the Back

Pros: Flexibility. Looks cool.

Cons: Requires negotiation with neighbors.

Okay. So the wall seems a little unwelcoming. A little Ming Dynasty. A little Minuteman-esque. The question then becomes where to put the new Austinites that are flooding our city like shaggy-haired Canadians at SXSW. Potential answers are many, ranging from massive public investments to small individual actions.

Which brings us to a tile-roofed two-story turquoise structure on a spring afternoon. Inside, Lori Renteria is in her sunny bathroom, showing off the Jacuzzi tub and the blue tiled walls, all designed to be accessible when she's old and decrepit. "You wheel your chair on over here," she says, stepping into the shower, "and your grab bar is here, and you put your fat ass here, and your home health worker is here," she says, pointing and wall-slapping as appropriate.

The bathroom is on the second floor of Renteria's "castle," a recently completed garage apartment behind the squat, six-room cottage where she raised her three kids. Renteria considers the high-ceilinged, airy efficiency her contribution to neighborhood stability: a place she and her husband can retire, leaving the front house available for one of her kids to live in, or to rent out if needed. And, she actively encourages her neighbors in the East Cesar Chavez neighborhood to do the same.

"If we're going to help families hang on to their property, we need to let them go dense on land they already own," says the compact, fiftysomething redhead. "When our kids grow up and need space for a new family, it's one way to keep families owning a piece of the rock."

A garage apartment won't work for all families. There are the skyrocketing construction costs that put even a small, simple garage apartment into the $80,000 range; plus, once the tax man catches sight of it, you can expect your appraisal to jump. Nevertheless, as she strolls the shady alleys around Haskell and Navasota streets, a few blocks from where Town Lake runs beneath I-35, Renteria points out how infill is already a de facto, grassroots reality: a cinderblock shack here, a newly built backyard house for grandma there. Ironically, infill is often seen as the enemy of affordability, as developers face off against neighborhood associations terrified of escalating property taxes. In the Blackland neighborhood across I-35 from the UT campus, for example, the neighborhood plan discourages accessory dwellings as a way to make the area less appealing for developers.

East Cesar Chavez doesn't like tear-downs or high-end condos any more than anyone else. Still, in a deep-rooted, Hispanic neighborhood where extended-family living is already the norm, the East Cesar Chavez neighborhood plan takes the pragmatic approach: It embraces do-it-yourself infill as a way families can continue to afford the land beneath their feet and keep the kids from being forced out of a ZIP code with only about 7,000 housing units total.

Ironically, that plan collided head-on with another affordability strategy: ordinances aimed at keeping property taxes down by limiting the size of garage apartments and duplexes. Renteria is not shy about saying she has felt screwed over by such ordinances in the past and has raised the alarm over elements of a proposed McMansion ordinance, specifically a proposal to limit the number of nonrelated adults who can live in a single dwelling. She's not alone: Mark Rogers of the Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation, which has built about 100 affordable housing units in Central East Austin over the last 25 years, has also run afoul of duplex-regulation rules meant to make life hard for developers. Thus this warning, or what we might call Renteria's Law: "What works for one neighborhood doesn't work for all."

Solution No. 3: Divvy up the Dirt

Pros: Fits more people into the same amount of space.

Cons: Fits more people into the same amount of space.

When homeowners think "affordable housing," they tend to think about valuations on large-lot single-family dwellings. They think, "My property taxes are going up" or, perhaps, "That Californian who paid $350,000 for the house next door is kind of a jerk." For organizations working to provide housing for as many working families as possible, the perspective is a little different. They think "cheap dirt."

More specifically, "Why isn't the dirt cheap?" Because it ain't: You have to get pretty far away from downtown to find a single-family lot going for less than $80,000. This trend is forcing changes for longtime affordable-housing providers.

Blackland Community Development Corp., which owns about a quarter of the single-family houses in the neighborhood, has decided just to go out with a bang. The organization is working with the UT School of Architecture to build a "green block" – seven homes plus communal gardens, composting, and other sustainable amenities – on the last few undeveloped lots BCDC owns. After that, the organization will continue renting to families earning less than 60% of the median family income (about $40,000 for a family of four), but will develop no more projects. Even finishing the last project may be a stretch – to keep costs down, BCDC has decided not to finance the project to avoid paying interest. "We're going to use bake sales and donations and grants," said Bo McCarver of BCDC. "This is all the land we're ever going to have, so if it takes us eight months or eight years, that's all right."

Other organizations that plan to stay in the game are evolving away from the single-family model and toward the "dirty 'D' word": Density. Habitat for Humanity, for example, has for years built single-family homes, which it sells on zero-interest loans to families earning between 25% and 50% of the median family income. To keep buyers from flipping their homes to cash in on gentrification, Habitat requires buyers to split any sale profits with the owners if they sell before the note is paid off, usually 20 years. This "equity-sharing" policy encourages owners to stay put; or, if an owner decides to sell, it at least provides Habitat some cash with which to build a home for another low-income buyer.

At least, that's the way it used to work. Now, land prices are so high that even equity-sharing can't keep Habitat in the game for long: You can't sell a single-family house for $65,000 on a lot that costs $100,000, not without a major subsidy. In the short term, Habitat is economizing by developing larger projects, such as a 43-unit subdivision planned for northeast Austin. Looking toward the future, however, Habitat faces a choice: either develop single-family homes in suburbia or develop more units on the same land. "I believe in homeownership," said Michael Willard, who directs Habitat for Humanity in Austin. "However, when it gets to where I can't find land except at $80,000, our organization needs to say, are we getting the biggest bang for our buck?" He predicts duplexes, condos, and townhomes in the organization's future.

Density does come with a cost. While multifamily housing can fit more people on less dirt, it also includes expensive features, such as parking garages and elevators, that raise the cost well over the roughly $75 a square foot that is currently about as cheap as you can build. And it's also not without controversy, as neighborhood groups often oppose multifamily projects – citing neighborhood character, concerns over rising property tax appraisals, or (ironically) plain old-fashioned opposition to living near "those people." But when the alternative is closing up shop, affordable housing providers are willing to get creative. The Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation, for example, is considering ways to profit from the gentrification that now seems inevitable. The idea is to buy a lot to subdivide and build two houses on: one affordable unit, and one yuppie house. The latter, said GNDC head Mark Rogers, "would basically pay for the lot and the other house, which the neighborhood would have as a long-term rental house. It's a nice, equitable thing."

It is, however, a rental, which does not have the sexy defenders-of-affordability glamour of, say, helping grandma fend off the real estate speculators. (The GNDC has done plenty of that, too.) But after 13 years fighting for the neighborhood, Rogers has come to believe that rental housing is a critical piece of the puzzle, if for no other reason than that it's the only kind of housing stock that is permanently affordable.

"In this neighborhood, about 15% of the units are owned by the corporation. If they weren't, we could say goodbye to any of it being affordable at all," he said. Now, the goal is "to try to maintain at least some kind of balance and diversity, so down the road, people who had some sort of ties to neighborhood can maintain those ties."

Solution No. 4: Supportive Rental Housing

Pros: Permanently affordable. Helps the lowest-income Austinites.

Cons: Sometimes annoys the NIMBYs.

Karen Brown may be 48, but she has the eyes of a 17-year-old. They roll dramatically, sparkle mischievously, and squint conspiratorially. They were doing all the above on a recent morning as she recounted all the new friends she's made since moving into Garden Terrace, an 85-unit former nursing home now run by Foundation Communities, a permanent supportive housing community.

"This place has empowered me," she said, kicked back in a blue easy chair in her immaculate room, adorned with photos of grandbabies, Christian kitsch, and a jade-elephant collection. "I haven't had a stable relationship, a stable job, or a stable sense of self before moving to Austin and utilizing the programs here."

Garden Terrace is what's known as permanent supportive housing, which provides on-site job and social services in complexes with very cheap rent. Padding the halls in fuzzy pink slippers, hollering hellos to other residents, Brown shows off the amenities: the lounge where the residents just had a dance party, the computer lab, the Goodwill outpost. Brown was homeless when she moved to Austin, victim of a divorce that featured, she says, things like defending herself against her husband's blows with the glass candy dish she broke by being knocked onto it. Her first step was transitional housing, which is free or very low-cost housing for the most vulnerable: the homeless. The market doesn't provide this housing, so only about 2,000 beds are available in Austin, provided by nonprofits such as the Salvation Army and SafePlace, which aim to help the homeless get sober, get a job, do whatever they need to get back on their feet.

Many have been down so long that they can't bounce right into the job market. That's where supportive housing comes in. It's very cheap – the basic rate at Garden Terrace is $300, including utilities, for a dormlike room – although for a minimum-wage worker earning $1,000 a month, it still barely counts as "affordable." The staff involved in helping residents toward self-sufficiency, plus the heavily discounted rent, means this is a pricey proposition that the private market won't provide. For that reason, some advocates list it as the greatest area of unmet need – Austin only has about 500 supportive housing units – yet with some of the greatest payback to the community. "It works," said Walter Moreau of Foundation Communities. "This is a real solution to make sure the homeless population in Austin does not grow."

These projects work because tax credits and subsidies can cut the development costs dramatically. Foundation Communities just got zoning approval for a new supportive housing project on Ben White for which tax credits will cover half the $8 million cost. In fact, the tax credits for low-income apartments are so appealing that according to Moreau there's a bit of a glut of cheap rental units (albeit without the services of Garden Terrace), especially because a soft rental market has kept apartment prices flat for several years. Still, with average rents now pushing $800 for a two-bedroom unit, it's hard for a low-income family to put together the savings to make the next step: buying.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon recently, a 32-year-old mother named Virginia watched from behind amber-tinted sunglasses as her children scampered around a Montopolis Easter party. Virginia (who didn't want to give her last name) says she lives "the good life" compared to most folks she knows – after pulling herself off welfare, she has a data-entry job that pays more than $11 an hour. With the $9.75 an hour her husband earns at Wal-Mart, she feels like they do all right. But since moving out of a public-housing complex after her oldest son started hanging around "bad kids," it's been tough to make ends meet for her seven kids and the three-bedroom, $820 apartment she rented near William Cannon. It's a nice place, she says, clean and safe. "But it's not mine," she says. "I want a place my kids can go that's mine, that's home."

*Oops! The following correction ran in the May 26, 2006 issue: In the news feature, "Looking for Cheap Dirt," by Rachel Proctor May, a photo subject was misidentified. In the photo for the section called "Solution No. 4: Supportive Rental Housing," the caption should have read, "Garden Terrace tenants James Ingram and Karen Brown." The Chronicle regrets the error.

Solution No. 5: Community Land Trust

Pros: Permanently ensures affordability; enables very low-income people to get into homes.

Cons: Limits the amount of equity accrued by homeowners, undermining one of the main reasons to own a home in the first place.

There are a lot of ways to spend money helping low-income residents get into or stay in their own homes. Until now, the problem with all of them was they don't ensure permanent affordability: once in the affordable home, a buyer can sell it to whomever they want for whatever price they can get.

Enter the community land trust, a tool the city is currently considering (staff presented a report and recommendations to the City Council on May 4). Under a land-trust situation, the city would own the land and lease the home atop it to a low-income resident. For all practical purposes, the resident is the owner: She can add onto the house, paint it purple, refuse to fix the roof, build a turtle pond, whatever. The only limitation is that when the owner decides to sell, it must be to another low-income buyer at a price he can afford. In the meantime, the owner is only taxed on the value of the house itself, meaning nearby valuations won't send her taxes through the roof.

Of course, for many buyers, the whole point of owning your own home is to create wealth. By limiting the equity a person can build, the CLT requires people to take on all the hassle of owning and maintaining with significantly reduced benefits. "That's the sticky point, whether people will be willing to buy one of these houses if they're not going to be the true owners," said Sabino Renteria (Lori's husband and another longtime housing advocate.)

Mark Rogers of GNDC agrees that the CLT isn't perfect. But, he adds, "if it's a family that's not otherwise going to be able to own a home, it may be worth it." One thing on which everyone agrees is that if the city is going to give land trusts a try, it needs to do so soon: the higher the land costs go, the less the city can afford. "One thing a community land trust does that no other tool does is preserve that affordability long-term," said Kelly Weiss of the Austin Housing Finance Corporation. "While it's a larger investment up front, we have a very small window to create [permanent] affordable housing. If we're not able to do it now, we will miss that window."

Solution No. 6: Downtown High-Rises

Pros: Environmentally sound, symbolically potent.

Cons: Expensive as hell.

When dirt is expensive, the more units you can fit on an acre, the cheaper they can be. So, if we build taller and taller skyscrapers into our sunny blue skies, presumably we could whittle the land costs down to nothing, right? Unfortunately, that's not quite the case. The price of steel, the engineering complications of going vertical, as well as the price of downtown dirt all add up to make downtown high-rises among the most expensive kinds of buildings out there: nearly $300 per square foot.

Still, the dream of a downtown that's not just for the gelato-slurping Prada set is very much alive, as evidenced by a forum in mid-April to debate financing, policy, and construction tools for squeezing affordable units into the dozen-odd downtown buildings already in the works, and the many more sure to follow. Throughout the presentations from nationwide experts, it became clear that affordability downtown is possible – if the city is willing to invest the resources.

The question then becomes one of values: How much is Austin willing to pay to get the affordable units right in downtown, as opposed to locating them in nearby neighborhoods? "Maybe you're spitting in the wind trying to get affordable housing right in the downtown," suggested architect Michael Pyatok, whose affordable housing projects in West Coast cities are concentrated in "inner ring" neighborhoods – the idea is to give low-income residents easy access to downtown with a lower price tag. (Even that's no silver bullet. Take CapMetro's planned Saltillo district. The 11 acres of three- to five-story condos, apartments, civic and office space just east of I-35 at Fifth Street fits that description, but neighbors are up in arms because they want half the units in the project to be family-sized and affordable, while its developers howl that anything over 25% is financially impossible.)

For affordability advocate Heather Way, it would be a "cop-out" to give up on downtown without trying. "We can't just say, this part of town is going to be affordable and this isn't," she said. Other housing advocates, like Walter Moreau of Foundation Communities, aren't so sure. Foundation Communities' properties are already scattered around the highways on the edges of town, because his goal is simply to get a high-quality roof (and amenities) over as many heads possible. "If it costs twice as much to do affordable housing downtown, unless a special funder steps up" – he paused and shrugged – "I want to serve twice as many people."

And thus commences the search for a special funder. One possibility is to acquire state-owned property (such as those ugly-ass parking garages east of the Capitol), which the city could incorporate into a land trust. For Mayor Will Wynn, it also seems possible to find incentives that don't eat up much of the city's affordability capital, such as allowing developers to build less parking. He also "challenges" the community to think broadly about affordability: Using his own 2,500-square-foot condo as an example, he explains how multifamily living reduces energy costs (recent bills have been in the neighborhood of $45 a month) and enables families to get by on one car rather than two. "We need to raise consumer awareness of how much we're all spending on our cars," Wynn said.

In the end, it's a matter of priorities: how much the city is willing to spend helping whom, and how. The contradictions and competing needs, are maddeningly complex: Owners vs. renters. Short-term assistance to families needing help right now vs. long-term investment in assets the city can own forever. Existing residents who like their neighborhood the way it is vs. new Austinites who also want their own piece of central rock. Even, to a certain extent, central neighborhoods vs. suburbs. That is, even if housing prices never rise another dime, and even if we find a way to create thousands of new affordable units in the center city, there are simply going to be more people in Austin than homes in central-city neighborhoods. A just vision of affordable housing, then, must deal with the livability and transit-accessibility of the cheap suburbs certain to sprout on the edges of town.

It's going to be expensive. It's going to be dirty, but that's where it all begins: the dirt beneath our feet, and the number of people we're willing to share it with.

Solution No. Gen X: Stencil "Yuppies off the Eastside" on Stop Signs and Dumpsters

Pros: You feel cool.

Cons: The yuppies do not care what you think. Plus, that blocky font looks suspiciously like latté.

Can the Bonds Save Us?

The biggest potential for a cash injection into Austin's housing resources is a housing bonds proposal tentatively scheduled to go before voters in November (now in some doubt because of the controversy over the potential costs of Proposition 1). The citizen's committee charged with putting together a $614 million package of needs allotted $67.5 million toward housing; City Council is targeting a final figure closer to $500 million, so the whittling process now in progress will test the community's commitment to affordable housing, among a long roster of other needs. Last week, staff concluded its own recommendations to the council – within a total package of $536 million – by proposing $50 million for affordable housing. Within that category, $30 million would go to rental housing for the neediest (below 30% of the median family income level), and $20 million for home-ownership programs aimed at families in the 50-65% MFI range.

The council's public hearing on the bonds is scheduled for May 18, with a final approval of the overall package and the ballot language in early June.

Because bond money usually goes toward capital investments, programs that help individual buyers (such as down-payment assistance) without permanently adding to the city's affordable stock are likely targets for cutting – they didn't appear on the staff recommendation. The same goes for emergency repair funds, a program that helps needy Austinites stay in their homes by giving people in run-down homes an alternative to selling to developers.

Jeffrey Richard of the Austin Area Urban League supports the repair program, pointing out that a new roof can literally transform the life of a fixed-income senior, and that the need is tremendous. With about $1 million, the Urban League helped around 600 families last year, but the program still has an 18-month waiting list for many repairs. "Most people think, 'We need to build affordable housing.' We think, we need to keep housing that is affordable continually livable."

But with bond money limited, the city is exploring alternative funding for programs like the home repairs. One compromise being kicked around is the possibility of funding major renovations on longtime residents' homes in exchange for them donating the property to the land trust. That may seem a high price for some homeowners (or, perhaps more precisely, their heirs) but it is akin to the "reverse mortgage" that already exists in the open market in the wake of recent changes in state law. The city also hopes to get private companies involved; a so-called Mayor's Challenge aims to double the Urban League program to $2 million through private philanthropy.

Over the next few weeks, council will set the final bond package that will go before voters. Even at this late stage, it will be a tug-of-war among different spending areas – every dollar for housing means less for needs like buying open space or fixing our sorry drainage infrastructure – but also among different ways of addressing the vast need for affordable homes in Austin. – R.P.M.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.