What We Carried (Away From Winedale)

Lessons learned about theatre and life by program alumni

Fri., July 23, 2004

Terry Galloway

When I was an undergrad at UT, I'd been kicked out of the theatre department because I was deaf and had a sometimes-mild, sometimes-whoa speech impediment. It was Doc who saved me from the humiliation of that rejection. It was Doc who told me that I had as much right as anyone to be up on that stage performing the language of Shakespeare. It was Doc who put me up there and gave me the roles that he thought suited my soul and helped me struggle through the doing. It was Doc who inspired so much of the ethic of accommodation that informs Actual Lives, Austin, the performance group of people with disabilities that I co-founded with Chris Strickling and Celia Hughes.

In 1976, I helped found Esther's Follies. That summer there were only a few ex-Winedaleans at Esther's, but by the fall eight out of 14 people on that stage were refugees from Winedale. Esther's was in an old pool hall then, and the only way you could enter was in the back from the alley. The old stage, like the existing one, was flanked by a window, but we didn't have a lot of chairs, so most people sat on the floor. We did have a bar but no liquor license. Doc had heard about Esther's and knew that a lot of us were involved, so he dropped by to catch a show. He loved it, got what it was about right away, saw how influenced by Winedale it all was. That next week, he showed up with two big kegs of beer. He set 'em up out back near the entrance with a little sign that said "Free." Our popularity soared. – Terry Galloway; '71-'75, '80

Alice Gordon

I don't think Esther's Follies in its most inspired, early days [1977-1979] would have worked at all without Shakespeare at Winedale. There were anywhere between six and a dozen ex-Winedalers in the troupe back then, maybe more – it tended to expand and contract weekly, sometimes reaching as many as 40 players. They brought a kind of anarchic organizing principle. We were used to working in groups, with no appointed directors, just everyone pitching in with ideas, and taking big risks and trusting – well, most of the time trusting – that, if not for every fall on our faces in rehearsal, perhaps for every 10, 20, or 30 falls, something amazing might happen. That kind of passionate collaboration, along with the good taste we all had gained by studying Shakespeare in such rough-sacred territory as Winedale, became the way Esther's caught fire. I don't know if they still work that way today. But I hope so. – Alice Gordon; '73-'75

James Loehlin

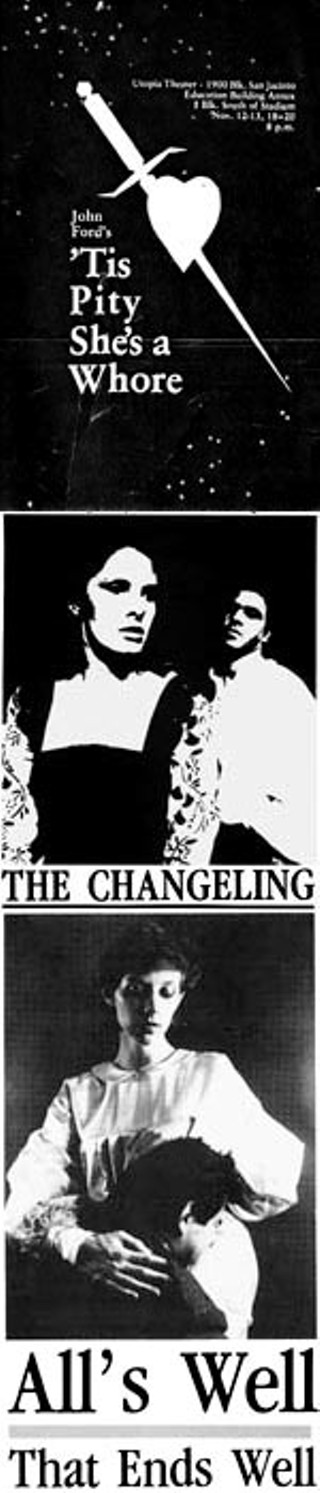

The first year after I was at Winedale, I was lucky enough to be part of a group that put on John Ford's Jacobean tragedy 'Tis Pity She's a Whore in the Utopia Theater at UT. There were a number of Winedale alumni – Steve Price, Robert Michna, Bill Friedman, Brian Foster, Shari Gray, and the late Alan Fear – Kathy Catmull was the female lead, and the group was directed by an Englishman, Robert Osborn. It was an eclectic group of people, but somehow it all really clicked, and we were able to get a lot of Winedale working methods adapted to a very different situation.

The next year I had an experience that made me realize how difficult it is to recreate Winedale outside of Winedale, how much the experience depended on the environment, the isolation, the guiding presence of Doc. A group of former students tried to put on an English Renaissance comedy, The Knight of the Burning Pestle, and the whole thing fell apart through entropy; we didn't have the centralizing influences, the creative crucible of Winedale. It was as a result of that experience that I decided to try directing. I did a couple of other plays with ex-Winedale students, The Changeling and All's Well That Ends Well, and both were very positive experiences. They helped me see how different Winedale was from a more traditional production process but also how much of what I had learned at Winedale could be applied in other situations. – James Loehlin; '83-'84; current director

Steve Price

The more theatre I've done and seen since I was at Winedale, the more distinct and singular the program seems to me. Part of it is the utter improbability of the particular combination of elements (college students + Shakespeare + Texas summer heat + old hay barn = ?). Partly it's the emphasis of process over product, but that's just the beginning. Shakespeare at Winedale is freedom in the purest form I've encountered it. Students are fettered by none of the business or artistic constraints of the professional stage, none of the "real life" distractions (jobs, feeding yourself, etc.) of the amateur one. All you're supposed to do out there is work hard and do your honest best at playing Shakespeare. I can't imagine a better human existence. Like Bardolph says in Merry Wives when he's suddenly tapped for his dream job: "It is a life that I have desired. I will thrive."

Shakespeare at Winedale has so little to do with theatre and so much to do with everything else in life that matters. A good summer at Winedale is only the beginning. It sets up the real challenge (or is it a temptation?) for anyone lucky enough to reach that point: How can I live the rest of my life this fully and intensely? Doing plays and pursuing a life in the theatre make a lot of immediate sense, and theatrical pursuits have their own particular set of challenges and rewards. But the path that Shakespeare at Winedale can illuminate is much, much broader than any specific occupation or career. – Steve Price; '82-'83

Lana Lesley

We formed Rude Mechs in part out of a dissatisfaction with traditional hierarchical structure in the theatre. We wanted to collaborate and gain experience in every aspect of the theatre: producing, marketing, design, acting, directing... We wanted artistic collaboration from everyone involved in creating work for the stage. I can't speak for all the Rudes, but I doubt I would have craved artistic collaboration on the level I do if I hadn't been in the trenches at Winedale sewing costumes, running the light board, learning lines, hauling trash to the dump, dragging the kegs all over the property, directing scenes, sweeping the stage, fixing the roof ... the list goes on. It is why we are producers as well as artistic directors and why we do it together as a collective.

I got along with Doc so well and listened to him so intently because he's a scholar wrapped in a jock suit. He was every athletic coach I ever had. I wasn't shocked at all when I exited the stage one afternoon, and he was waiting at the end of the aisle to poke me in the chest 'cause I screwed something up. I was totally prepared to have to do laps in my Bianca costume – joke: We never had to do laps.

What Doc inspires (and it manifests as theatrical energy, good journalism, good medical practice, or good lawyering) is a strong work ethic, and he teaches you to apply it to everything you touch out there. That is what I remember learning: how important a strong work ethic is to a group, to the process, to your own personal satisfaction. If ex-Winedalers have anything in common, we might all understand the importance of process. – Lana Lesley; '91, '93

Kirk Lynn

I started writing plays while an undergrad, and professor Frank Whigham suggested I apply to Shakespeare at Winedale, more as a crash course in theatre than a study of Shakespeare. I went to be "interviewed" by Doc, but instead of asking me questions Doc just said, "Tell me about yourself," then sat there, silent as a stone. I spoke for a while and then paused. Nothing from Doc. Not a "thanks for your time," not an invitation to continue. I spoke some more, paused. Same thing. I got angry and thought, "Fuck it. I'll see how much this guy can handle." I started telling Doc about every book I'd ever read, every drink I'd ever drunk, every rap album that moved me. But, of course, Doc won the battle. I finally ran out of babble. Who was I kidding? This guy can listen to kids perform Pericles. My best banter can't even approach that level of logorrhea. I left his office, fumed off to my next class, then stomped my sandals back to Dr. Whigham to ask, "Why did you recommend that asshole?" Dr. Whigham told me that Doc had just come by to ask the same thing. When Doc is on, his Zen is superb.

I was accepted to Shakespeare at Winedale and learned more than literature through performance or the basics of theatre production. I played the ghost of Hamlet's father to Lana Lesley's Hamlet and Madge Darlington's Horatio. I discovered that there is a kind of person that I can work with, drink with, argue with, and never feel anything less than love for. Theatre is a particular fetish for long hours which offer nothing more than long odds on no better prize than obscurity. It is a ludicrous proposal that Shakespeare either can or should be performed by kids in a hick town in Texas at the height of the summer's battering heat. The spirit of that proposal lives on in the Rude Mechs' hope that the American avant-garde theatre can and should have home in Austin, Texas. – Kirk Lynn; '93

Madge Darlington

It was a particularly hot summer with temperatures reaching well above 100 on many days and a heat index high enough to be considered hazardous on most days. As much of the work we did was outdoors or in the non-air-conditioned barn and often in costume – mostly tights overlayered with Elizabethan-looking attire – keeping hydrated was essential to everyone's health.

At one point, the class was struggling with Hamlet, and Doc told us that he could not see any evidence that we were going to overcome our struggles because we were not working as a group; we were not listening to each other, we were letting personality conflicts interfere with our work, and each of us was so absorbed with our own personal struggles that we couldn't possibly come together as a unified ensemble to tell the story of the play. In addition, we were struggling with the weather. The heat, along with our poor morale, drained us of our physical, vocal, and emotional energy.

I don't remember how it started, but at some point members of the class tacitly decided to start handing each performer a cup of Gatorade and a frozen towel as he or she exited the stage. Suddenly we were racing each other to see who could be first to offer a colleague a drink and some needed relief. Our personal conflicts did not disappear, but those conflicts were no longer our focus. We were on the same team, working together to stave off heat exhaustion, taking care of each other in a way that allowed us to focus on the work of the play and the playfulness of the work. Our individual and collective performances improved immediately. We had begun listening to one another to know where we were in the scene in order to know when to position ourselves for the next exit by a performer. By the end of the summer, we had formed an incredibly tight ensemble, simply by caring for one another. – Madge Darlington; '89-'90, '93-'99

Anne Engelking Earvolino

The whole philosophy for Bedlam Faction from the get-go was über-Winedalean: Get folks together and play! We (Robert Deike, Rob Matney, Andy Bond, Matt Kozusko, Shanna Smith, Mike Mergen, Mark Lovell, myself, and others) each contributed $50 of our own moolah to "get in the box." And it went from there. Some Winedale-influenced moments from those early days:

We had no "director."

We started each meeting/rehearsal in a circle.

We sang during every intermission.

We held our first "performance" (run-through) outdoors, offsite, away from the "world."

We required that we have our lines memorized before the first rehearsal.

We (John Botti) wrote our own music.

We (Shanna Smith, Susan Baker) put together our own costumes.

We played like there was no damn tomorrow (a line from our first mission statement), and we gave ourselves to anyone who wanted to see theatre for a reasonable price.

I think it's important that each of those lines begins with "We." There was no other option but to act as a collective, for without the collective, as Winedale taught us, there was no play, or play, in the true sense.

The play's the thing ... – Anne Engelking Earvolino; '94-'95, '98