A Shared Vision

Combining generosity and hard work to build the Institute of Hospitality & Culinary Arts at Travis High School

By MM Pack, Fri., Oct. 11, 2002

During the last week in October, the brand-new Institute of Hospitality & Culinary Arts at Travis High School will mark its grand opening and dedication with a series of celebratory events. This past year, I've watched the development of this impressive program with interest, happy to live in a city where the professional culinary arts are taken seriously enough that students can begin studying them in high school. The inauguration of another high school culinary program in Austin is indeed cause for celebration. Bowie High School has had a vibrant and effective program in place since the school opened in 1989, and Del Valle High School has a program for that district. However, an additional reason to celebrate the latest institute is the story behind its development, a story about a vision of improved education for Austin students, and a community's combined efforts to make a piece of the dream real.

The new Travis Institute absorbs two prior programs at Austin and Crockett high schools that moved to the Travis campus in the fall of 2001, where classes became available to all AISD students who want to study hospitality or culinary arts. There was one significant obstacle, however; there were no teaching-kitchen facilities at Travis. The program existed, but there was no place to put it.

And this is where the story gets good. A consortium composed of AISD, the nonprofit Travis Education Foundation, the Austin food service and hospitality industry, the local building industry, and many interested individuals all worked together to plan, design, fund, and build a 6,600-square-foot, state-of-the-art teaching facility that includes a commercial kitchen, a dining room, and classrooms, all in less than two years. And amazingly, fully 70% of the funding, services, building, and materials for the $1.3-million-dollar project were donated.

The Process

How did this remarkable feat occur? In a nutshell, it was through the efforts of a handful of dedicated people who saw the need and had the energy and conviction to spread the vision and convince the necessary players to join the team. The Travis Institute first evolved from collaboration between Patricia Bell, AISD career specialist in careers and technology, and John Blazier, an Austin attorney who is president of the Travis Education Foundation.

Bell, a woman of seemingly boundless positive energy, has been involved since the 1970s in cutting-edge development of school-to-work culinary education in New York, Ohio, and Michigan schools before coming to AISD in 1981. She taught the innovative and successful culinary curriculum at Bowie for 10 years prior to taking her current position in school administration.

Now, as career specialist, Bell serves as district-wide advocate, facilitator, program developer, team leader, and tireless promoter for family and consumer science programs, which include culinary arts and hospitality. "Part of my job is to show community and business resources what's going on in AISD. It's a two-way street: to get information about school programs out to the community, and to solicit community support for school programs," she explains. "There's a long history of the local food industry working with AISD's culinary program. They've always been involved in what we do; we go to them for direction, vision, and forecasting about what students need to know to enter the working world. Because of them, we've been able to keep programs current and viable, so kids graduate properly prepared for jobs or for further culinary education."

A couple of years ago, Bell looked at the existing culinary and hospitality programs at Austin and Crockett high schools and realized that for maximum effectiveness they needed to be combined and upgraded in a central location with more conducive facilities. Travis High School had the location, real estate available for new facilities, and importantly, an active education foundation. The Travis Education Foundation, under Blazier's leadership, is a nonprofit organization of businesspeople interested in improving Travis High School; their mission is to help upgrade the competencies of all students there and to create a better school experience for them. Other AISD schools (Austin, Johnston, and Lanier, for instance) have similar foundations; each works as a partner to help meet goals that the school sets.

As an example, the foundation has been instrumental in getting Travis up to speed with sorely needed computer labs, obtaining critical equipment and assistance from local high tech businesses. These 630 networked computers are used not only by Travis students, but also for evening computer literacy classes attended by more than 2,000 adults. The foundation also spearheaded the effort to instate a popular ROTC program at Travis.

And now, the foundation -- with the collaboration of AISD and the assistance and encouragement of the Austin food service industry -- has accomplished the unprecedented project of housing and supporting the Travis Institute. "Such a symbiotic model exists in many communities, where business resources help schools, and schools provide graduates trained and ready for work," Bell says. "What's unique about the Travis Institute is that a private foundation signed on to build a new facility on a public school campus, and to provide ongoing funding for its operation. To my knowledge, this is the first time in the country that an education foundation has made such a commitment."

John Blazier is a soft-spoken man, but the force of his personality is unmistakable, as is his ability to make things happen. He has a long history of community service in Austin, particularly in the areas of equal opportunities and resources in public education. Although an attorney, he also has a personal understanding of food service; as a young officer in Vietnam, he ran a kitchen that fed 1,500 people three times a day. As president of the Travis Education Foundation, Blazier seems to have an uncanny ability to get people to see his vision for students, and to commit their time, energy, services, and money to the cause. As Bell says of him, "He's a great motivator; he hits you at the level of, 'This is what we need to be doing as a society, what we should be doing as good citizens.' And most of all, he walks the walk."

When I asked how he managed to get such a high level of corporate, political, and individual buy-in, Blazier put it very succinctly. "Show successes, be passionate, let people know they're a necessary part of the process, don't ask for something if you don't really need it, and lead by example. You can't ask other people to give if you don't give yourself," he says. "Most people want to make a difference, to look at a situation and be able to say, I did something and now it's better. Also, we must give a lot of credit to Superintendent [Pat] Forgione and the school board, who had the courage and trust to enable such an out-of-the-box solution."

This approach certainly seems to work. Some -- but by no means all -- of the services donated to building the institute were the architectural design by Jim O'Neil of Pfluger and Associates; kitchen design by Michael and Joanne Counihan; general contracting by F.T. Woods (who bid the project at cost and asked all the subcontractors to do the same); structural engineering by Rick Guerra of Jose I. Guerra Engineering, civil engineering by I.T. Gonzalez; stone and concrete products by Texas Building Products; and concrete work by Juan Rangel & Family.

It also seems that such an approach breeds continuing goodwill. I spoke with some of the design and construction team members; they had nothing but praise for one another, as well as for the AISD construction office headed by Hector Hinojosa and the various city of Austin building inspectors. "On this project, there was none of the adversarial relations, the finger-pointing, that can sometimes happen among architects, engineers, contractors, and suppliers," O'Neil told me. "We became a team with a mission to accomplish, and we'd say to each other, 'Wouldn't it be nice if every project went like this?'"

The Facility

So now the Travis Institute for Hospitality and Culinary Arts is built and it's most impressive, indeed. Any restaurant would kill for its spacious new kitchen. It's all there, from a prep kitchen to dishwashing space to large walk-in refrigerator and freezer to ample worktables and storage space. Much of the equipment, from stoves to industrial mixers to pots and pans, is recycled from the earlier programs at Austin and Crockett.

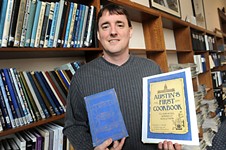

There is a classroom shared with the sister Hospitality Program, and a dining room that can seat 80; it will be used for special events and a future fine-dining lunch program similar to the one now at Bowie. Chef Instructor Olivia Balderrama (see "Olivia Balderrama Comes Full Circle") is working to find space for the culinary library; she's already gathered a substantial collection of books and periodicals.

There's a snazzy new POS (point-of-sale system -- those computer touch screens you see waitstaff using in restaurants) that transfers order information into the kitchen and into inventory. IBM donated the hardware and Aloha Technologies donated the POS software. There is built-in capacity for distance learning through video.

The Program

The Culinary Arts program is based on the existing one at Bowie High School; chef Balderrama works closely with Bowie's chef Richard Winemiller to develop a consistent, systemwide approach. The biggest difference is that the institute is open to students from any AISD high school and the Texas School for the Deaf; there is a capacity for 200 students, which they expect to be filled by next year.

The chef-instructors teach to TEKS (Texas Essential Knowledge Skills) that are established by the Texas Education Agency. Students spend their first six weeks in the classroom learning kitchen safety and sanitation. They are eligible to take a national exam to get certified by the National Restaurant Association, and most of them pass it.

After that, 75% of students' time is spent hands-on in the kitchen, where they learn knife skills, food preparation, measuring, recipe development, food costing, front-of-the-house operations, and more. Once they've completed the program's two years, they know basic kitchen skills and they're eligible to test out of some classes in professional programs, such as ACC and other schools. The program places much emphasis on presentations by industry professionals and includes site visits and tours for work-based learning. There are ample opportunities for students to work with professional mentors and to shadow chefs as they work, as well as for summer internships around town. Some of the professional partner/sponsors are the Austin Hotel/Motel Association, Texas Restaurant Association, Driskill Grill and Bar, Hyatt Hotel, Four Seasons Hotel, St. Edward's University, Texas Culinary Academy, Whole Foods Market, Word of Mouth Catering, and Buca di Beppo Restaurant.

As well as Culinary Arts, the institute contains a hospitality track, taught by Jayma Vaughn. This program is less direct instruction and more like an apprenticeship with working professionals. Students work their first year at the Hyatt Hotel; they spend the second year at the Four Seasons, rotating among all of the hotels' departments. Culinary and hospitality students work together on special and community events.

The Students

Who are the students at Travis Institute? Currently, there are 40 studying culinary arts; half are second-year students, who take greater responsibility in the kitchen, performing leadership and peer-mentoring roles. This year, there are five "traveling" students who come from other schools -- Austin, Crockett, Anderson, and the Texas School for the Deaf. These travelers spend half a day at their home campuses and half a day at Travis.

According to Balderrama, the culinary program includes all types of students, including those in gifted-and-talented and special education classes. She says that an important element is how they all learn to work together, collectively channeling their incredible adolescent energy. "The students really bond and learn to respect one another's abilities, as well as each other's space. They also get really motivated by being surrounded by other students who are intensely interested in the same things they are."

About half the students come into the program because they love to eat or think it might be fun and interesting, but the other half already know that a culinary career is what they want to do. They all quickly realize the importance of math, science, and communication skills in the kitchen. I asked Balderrama about what I call the "yuck factor"; most teenagers I know are not exactly adventurous eaters. She laughed and said, "It's definitely there, but I tell students that unless they're allergic to something, they have to taste it. I also ask them, 'What don't you like about it? The flavor, the texture? What would you change?' They do learn to respect other people's work, and that it isn't acceptable to dismiss someone else's food without tasting it; they don't like it when someone does it to them."

And what's next for the Travis Institute? The foundation and the school district have big plans for expanded student and community use. "Now that we have the best high school culinary facilities in the country," Blazier says, "our next goal is to build the best public school culinary program in the country." ![]()

For more information about the Travis Institute for Hospitality & Culinary Arts, visit www.austinschools.org/ culinary or contact Patricia Bell at pbell@austin.isd.tenet.edu or 414-2679.