Hard Water

Second Place

By Sharon L. Dutton, Fri., Sept. 17, 1999

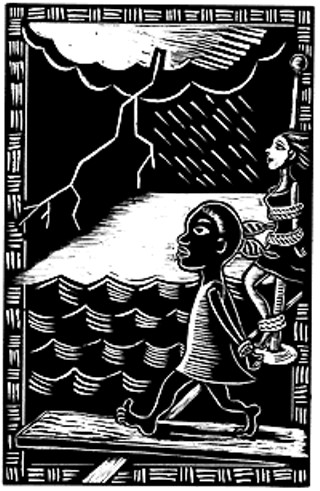

I climb up on the old wooden Coke crate and imagine walking the plank. Lightning flashes in the stormy sky. Next to me, lashed to a weathered mast, is the poor, long-suffering, achingly beautiful Maureen O'Hara. Her hair floats on the air like fiery satin ribbons. Mother insists that "impossible shade of red" can only be had from a bottle. Many nights I swim under the covers, drenched in sweat, trying to save poor Maureen. My pillow, Sugar Daddy and Barbie dolls take the brunt of kisses -- kisses from pirates, kisses from her. Kisses for me. I sigh for Maureen's courage and squirt stripes of liquid soap into the dishwater. I'm still too young to reach the old sink, but I know one thing: our fates have been decided. We will go down together. I wonder just how long I can hold my breath under water. Once I held it ten seconds longer than Terry Johnson at the Thorne Street pool. And for my prize Terry promised to kiss me "like they do in the movies." I'd had plenty of practice. When the time came, I puckered my lips Maureen-style and closed my eyes. That was right before Terry gave me a Double Deluxe Titty Twister that shot the kiss straight to hell. Of course, this is back in 1967, and my chest is as flat as an old man's ass. So here I am in my favorite red blouse and blue jean cut-offs, watching the water froth around the dishes. Doing time at the sink. Mother's carrying on again about the purifying goodness of water. Never mind that the scalding water killing all those germs is eating the skin right off my eight-year-old hands. She says water is "hard" when the soap bubbles lie flat like gray Necco Wafers. Bathtub rings are a reminder of good water gone bad. Mother, who believes cleanliness is next to Godliness, also believes in the weekly bath. We kids take turns hopping in and out of the half-filled tub of water every Saturday night. Prentis is always first, having learned early on that positioning is everything, even if you are a rent-a-kid. During the rest of the week, birdbaths are customary, but I usually wash from the sink on Saturday nights too. It's not safe. We don't call Prentis "fart bucket" for nothing. This is the same Prentis who plants boogers under the rope rug in front of the Zenith. Still, our efforts pay off. The hot water isn't all used up and the soft water man doesn't have to make any extra trips. This saves Mother money. So we're all truly saved. Amen.

"What's this word? Hmmm? What is it?"

Mother's voice gets loud. Her black licorice face is contorted, the first sign of a "blow out." While the other foster kids get ready for bed, flapping water under their wings and things, I scan the offensive word written in the corner of my Weekly Reader. Yes it's my writing; no, Ma'am I don't know why you're so angry, but I'm sure I won't be getting any dessert tonight.

"Right here -- this word!"

The red lacquered nail stabs at the paper, tears through it like a thunderbolt. Sure I'd seen the word before. Someone had written it in chalk on the sidewalk in front of the Harriet Beecher school, but I wasn't sure what it meant or even why I wrote it. Maureen O'Hara isn't helping much either. Her "delightful Irish brogue" stays locked behind her red ruby lips. Great. The hot dish water makes me want to pee. I brood, try to nurse the idea that somehow Jesus in heaven is interested in my bribe of Motown 45s.

"Do they teach you that in school?" As usual, Mother answers herself. "I'm sure they didn't teach you this filthy word!"

I look into her eyes to search for a clue to the $64,000 question, but all I see are black yolks. Her cartoon eyes beam invisible lasers straight into my brain. It's the same crazy stare she'd turned on me when I told her about Roger, the lone teenager of our bunch. During nap times, I used his diving mask for pretend undersea adventures with Jacques Cousteau. The "sea" was the green colored carpet in the upstairs hallway, filled to brimming with green-slime creatures. But the game stopped when Mother discovered the diving "mask" was really Roger's jockstrap. The perforated cup, I learned, was not meant to double as an aqua-lung.

The real science came when Roger showed me how he made "ice cream" come out of his thing. We often played with this amazing wonder, him trying to push it in without much success, while I rocked to an fro. All that rocking only made me sleepy for the nap I wasn't getting. Afterwards, we'd slurp ice cream sundaes topped off with Hershey's syrup and Planters nuts. I'd come to realize "doing it" was not something Roger cared to broadcast. He paid for my silence with those sundaes. This was my initiation into the secret world of adults. Adults always had their secret clubs. Mother was an Eastern Star, but that's all she'd say about the matter. There were secret books with no titles and mysterious badges, rings and funny looking hats. But my membership into this world was revoked the first time Roger refused me some of his sundae. I turned stoolie. No ice cream for me meant no ice cream for him. The next thing I knew, Dr. Trope was examining my thing and declaring it whole. "Just potent imagination," he'd said.

Abracadabra, presto-change-o. Just like magic, Roger and his mysterious ice cream making thing vanished, along with my piggy bank full of Kennedy half dollars. This is how I first made sense of the word "fuck," which looks a lot like the word luck, but add the offending hook and crossbar and everything changed. At that moment, I draw a Crayola line from the whole Roger episode to the word mother's glaring at. We stare at each other until Mother blinks and sends me to bed. Somehow it's over, but I know I've gone deep behind the line of adult territory again. I'm scared, intrigued. And to my way of thinking, the word needs further testing. What better place to try it than one where its evil powers can quickly be contained? That place is the HouseoftheLord, which I later learn is NOT the name of our church.

I enlist the help of my new foster sister Tammy. Her father died with a purple heart in some place called Nam. One pack of strawberry Now Or Laters deals her a hand in the caper. We wait for the right time to cluck the word that will transform Mother into a screaming meemie. Reverend Wright is just getting started in on his favorite sing-song-y prayer. The congregation is feeling the groove:

Well, well Lord (yessuh!)

The day is passed and gone (un huh!)

The evening shade's appeared (tell it!)

Might we all remember well (preach!)

The night that death drew near (Amen!)

This was the cue. Tammy and I set off an explosion of rapid fire "fuckfuckfuckfuckfuckfucks" over the bowed, collective conked head of God's children. Several people nearby think we've "gotten the spirit" and start speaking in tongues.

"And a child shall lead them!" shouts sister Buford. (Amen!)

Mother, who doesn't give a hang about Dr. Spock, (what does he know about kids anyway?) swiftly prescribes the dreaded leather strap to my things, right there in the third pew. Tammy's backhanded smack-dab into Prentis, the booger-bucket-boy, who's keeling over with laughter. We're wailing and crying, slinging snot everywhere. All the excitement kicks Reverend Wright into high gear.

And as we draw our garments by (Whack!)

Upon our beds to rest (Preach it! Preach it!)

We know Death (Whack!) has disrobed us all (Whack!)

Of what we have possessed!

The usher hands me a Kleenex with a solemn look, as if she knows my spirit's in a "whirl of trouble." And if the strap doesn't do the trick, Mother threatens to send me to a "psych-trish."

Mother Benson always had her own brand of language which tested the limits of my Weekly Reader. Let's face it. She had trouble saying certain words.

"Will you kids stop streaming?"

"Stop banging that streen door!"

"Oh, that's just a stratch! Stop streaming!"

Needless to say, it twisted us a little for schooling, but having learned the key to Mother's language we were able to decode other things. A "good cooga mooga" was Joanie Taylor, who lived across the street from us. She was the color of butterscotch. Mrs. Taylor wore rows of pink sponge curlers and chain-smoked Lucky Strikes. A "good boon coon" was any good friend of the "knee-grow" persuasion who played pinochle and drank Johnny Walker Red before falling down. None of these words ever appeared in the Weekly Reader, so I practiced writing them with a fork in the dishwater.

It's three years after Roger's disappearance, and we get another teenager. Marion is her birth name; she's from the South. Marion is "tired of eating pinto beans for breakfast, lunch and dinner." I figure the reason her family's packed her off is to make my life a living hell. It isn't by random choice that we share a room. I eye her coolly as she sings along with Sam and Dave, doing some dance called the Boogaloo. She says they're "boss" and switches dances. Now she's doing the Cool Jerk. Marion has an underarm problem, so Mother says. They try razors first, baking soda second. This, of course, does not prevent me from calling her "maggot." Maggot hates her pet name, especially when spoken by me, her arch enemy. She seeks revenge by routinely slipping a black and white photo of the Wolfman under my pillow. This paralyzes me and riddles my sleep with scenes from Creature Features. It stunts my growth. Another means of torture Marion uses is the hot comb whenever she presses my hair. Mother thinks I'm just "tender-headed." Then a miracle happens. God sends the Afro to set the hair slaves free.

Somehow I don't quite master the hairstyle. David Williams, my first official boyfriend, takes great delight in calling me "scare-fro." He gives my bushy "do" two quick yanks every chance he gets. I think I love him. He snaps my training bra because he says I'm frigid and don't know how to tongue-kiss. David Williams doesn't have "the informer" for a little sister.

Years twelve through fifteen are a hyper-blur. We move to the suburbs, where we are one of only six black families. We are no longer Negroes, we're black and we're proud! I am the talk of the pool, in my hand-me-down black swimsuit with built in titties and my Confidets pad sticking out the leg. No matter what the Confidets people say, you cannot go swimming in their pads. Our dog likes to fish the little blue bags out of the garbage and tear them to shreds. That's when I have to explain to stupid Prentis why girls bleed.

My bed-wetting habit develops right around the time my foster father takes up where Roger left off. The daily birdbaths don't do much to mask my problem, because Maggot and the Osgood twins always ask "who smells like pee?" Between all the bleeding and peeing I think I will die an early death. Surely he was just patting you on the bottom to get to bed. Lon Chaney, Bela Lugosi and Vincent Price star nightly in my dreams -- all the nightmare faces of my father. David Williams is wrong about me. I do learn how to tongue-kiss. Abracadabra, the bed-wetting problem disappears at thirteen, owed to Mother's strap and me setting the clock every two hours. I let Prentis torch my Barbie Dream House in exchange for his cool Captain Crunch mood ring.

The Jackson Five and the Osmonds battle it out on the charts. We are now proud Afro-Americans. Janet, my-best-friend-who-is-white, likes Donnie and I like Michael. We plan to name our children after them. Now there are only four of us kids left. Mother Benson says state dollars don't stretch that far. The informer-turned-pyro discovers matches. As Samantha and Darren Stevens argue with Endora, the fire in the coat closet ends up eating half the house. We become guests of the Mark Twain Hotel because our father's a big-shot head waiter. Each morning food's brought under warm silver domes to our suite. Mother saves the sticky buns from breakfast for our after school snack. All our teachers, friends and neighbors chip in and give us a record-breaking Christmas. Miss Read, my hated math teacher, even brings us used china. Mother wraps all the gifts in newspaper. Even the Kiwanis Club goodies that come already wrapped.

The Masons hold a big ceremony for my foster father, who is finally done in by unfiltered Camels. The fraternal brothers come dressed up in their fezzes and sashes; one carries a deer's leg and hoof, crisscrossed over his chest. Weird. They mouth mysterious things over his mummified remains. Blah, blah -- Howard was a master, third degree Mason. Blah, blah "-- a wonderful civic leader." I force myself not to cry; he doesn't deserve my tears. The monster is dead. I know because mother makes me touch him when I go by the casket. Later, in the limo, I stare out the window while Mother Benson "lambastes" me for "being a strange child."

Larry Simmons and I slow drag under blue lights in the basement, but I don't let him "french" me. I can see every piece of lint on his clothes, every bit of dandruff in his 'fro. It takes five more years before I can kiss anyone.

Eventually, Mother Benson gets a job buying "better dresses" for an upscale store. She even finds time to take sewing lessons at night. Now there are only three of us. We're trying not to disappear. Prentis masters beans and franks as his dinner specialty. Laurie, the informer, excels at dance lessons and discovers the joys of weed. I retreat to my books. Live other lives, invent other worlds.

We all found ways to make it through. When I look back into the space between me and those sometimes difficult years, I think about slate sidewalks with big chalk hearts drawn around words, or getting rug burns in my undersea world. I think about sitting bug-eyed in front of the double feature, eating homemade popcorn from greasy brown bags. It still makes me laugh to think about my first real spelling lesson. But mostly, when things get tight, I'm comforted by the thought of Maureen O'Hara and me braving the hard water. ![]()