Page Two: The Moment Belongs to the Music

John Sayles' 'Honeydripper' takes flight

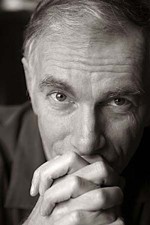

By Louis Black, Fri., Jan. 18, 2008

– Michael Ventura, "Hear That Long Snake Moan," Letters at 3AM: Reports on Endarkenment

"'I played what the sax man played,' says the old man. 'Only I played it on my guitar. There was a hole, see, and I had to fill it. I'm slidin' the notes, bendin' them around, playing blues riffs and harmonica runs and Sunday preacher Hallelujahs and it's all squawking out of that box of mine and it's starting to distort – but in the mood right? – and I can feel the people are with me. ... Maurice he's laughing over at his piano and I go till I burn that amp down.'"

– John Sayles, "Keeping Time," Dillinger in Hollywood

The music has always been there, has always been within us, pushing through our veins and in our heads. The very first attempts to release and invoke the music was done by banging branches and smashing rocks. It progressed from there. There's probably plenty of music we've all never heard trapped inside of us, carried by mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers, by the young and the old.

In the 1950s, in a rural black community in Alabama, there is a building nearly falling down but still standing. It is not too far from the crossroads long said to be the very one where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil. Almost every crossroads in the Deep South has been said to be the one where that bargain was struck.

In American movies, the greatest acts of redemptive transcendence are often personal: Fred Astaire starting to dance or John Wayne standing in the road, holding a rifle. In great rock & roll movies, this moment belongs to the music. Obviously there are folks playing instruments who are a crucial part of the magic. But the music is what causes a film to take flight, becoming greater than itself.

At the Toronto Film Festival, I saw John Sayles and Maggie Renzi's new film, Honeydripper, in a large theatre, with a completely racially mixed audience, which is more common to Toronto than Austin. At the end, the entire audience jumped up, giving the filmmakers a standing ovation that went on and on. As much as anything, they were applauding the power of music and the humanist beauty of its history.

The Honeydripper of the movie is the name of the club run by Tyrone "Pine Top" Purvis (Danny Glover). Maceo (Charles Dutton) works for him, as does his wife (Lisa Gay Hamilton) and his stepdaughter, China Doll (Yaya DaCosta). The Honeydripper has fallen on hard times. The club features female blues singer Bertha Mae (Mabel John, Little Willie John's sister), backed by Glover playing piano. As she seems almost anachronistic, folks no longer come to see her. A drifter (Gary Clark Jr.) passing through stops in, looking for a job, while an enigmatic street musician (Keb' Mo') playing guitar comments on life.

In the Deep South, everything is set against cotton. There is nothing quite as lovely as endless, powerful, white fields of blooming cotton. That lasts just a few weeks before it is picked – first by machines, then hand-pickers. Only you never really pick a cotton bush clean; there are always wisps of white decorating it. As lovely as the landscape briefly is, afterward there are tens of thousands of acres of bare brown bushes with bits of white all over; being there, you feel you are in the elephant's graveyard of toilet paper. In ways, looking fire-scarred, the fields are constantly whispering about the ghosts of history, of slaves and a civil war.

The movie is set in a time of change. Jim Crow (legalized segregation) is still very much in effect in the South, but the nascent civil rights movement is beginning to come into its own. In the age of the jukebox, live music is overshadowed. Even when there are musicians, rather than being piano based, the blues are becoming dominated by the sharper, more stinging sound of the electric guitar.

Adding to Pine Top's woes of being at the wrong end of this transition, just down the road a short piece is Toussaint's: a newer, sizzling, neon-highlighted club that is attracting the weekend crowds he used to see. Homey, warm, and well-worn, the Honeydripper is a distant, not really attractive relative of the newer club. Nothing there has gone right for a while. Glover, in serious trouble, knows what he has to do but has only one Saturday night in which to do it.

Sayles is a huge music fan; listening to the car radio, talking about new releases, or even just checking the soundtrack album for any Sayles movie is a dead giveaway. Given the way he looks at the culture, the people, and the flowing patterns of that relationship, he never gets caught up in the minutiae but is almost always more interested in the greater panorama. In a way, it is almost surprising, especially in light of the knowledge that an important part of Sayles is always working, always writing. Over the years, I've been to many concerts with the Sayles and Renzi team: Isaac Hayes, the Flatlanders, Lucinda Williams, and Lyle Lovett among others. Both of them love music, but after the show Sayles usually goes off to write while Maggie and I hit the bars and clubs. Around them, there is always music from car radios or home stereos. Another part of John is always carefully listening, and it almost doesn't matter what genre of music it is – jazz, rock, country, conjunto, polka, blues, or something else.

Still, this is the first film by Sayles in which his love of music dominates the whole film. Music is not simply the blood pumping through the body, but the body itself. Honeydripper is a great blues song: There is woe and there is hardship, but in the end there is redemption and glory.

There are many arteries pumping blood through American fiction in all media. Two of the most important themes, in direct opposition to each other, are tragedy and redemption. In order for a work to be tragic, the characters' possibility for redemption must exist even if it is never achieved.

Honeydripper has more power, grace, and delights than my critic-speak indicates. It is a film to watch over and over. Austinite Gary Clark Jr. shines, but the blues end up winning out over everyone. The film is set against the tragic. Issues of economic hardship, questions of faith, and the powerlessness of blacks in a world where they are rendered legally inferior, rather than being ignored, are crucial to the film. Hope struggles, and prayer is a common tongue. Whites hold the power, but blacks have largely learned how to navigate around them.

But Honeydripper is a joyous film, not a tragic one. It is much more a celebration of redemption than a depiction of oppression. As with all Sayles' films, it is about people and their lives – but here that's set against the spontaneous, "just grew" spread of the people's music, "and they called it rock & roll!"

In the moment when the pounding of the drums is inside you, rushing through you, the guitars and horns ripping – in that moment there is redemption. Some call it the devil's music, declaring that it is a blasphemous invitation to sin. But this is not the devil's music; this is the music of the soul and of redemption! The music strained through tribes and slaves, farming and industry, through Christianity and voodoo, is the music of America. Within us all is the power and the glory. Music brings this out, which is really what Honeydripper is about.