Numerous and Curious Tongues

Two New Books Reveal the Seductive Dissonance of Latin American Art

By David Garza, Fri., March 16, 2001

Twentieth-Century Art of Latin America

by Jacqueline Barnitz

University of Texas Press, 416 pp., $70; $34.95 (paper)

Mexican Suite: A History of Photography in Mexico

by Olivier Debroise; translated by Stella de Sá Rego

University of Texas Press, 306 pp., $60

There are so many problems to resolve when constructing an adequate survey of modern Latin American art that it almost seems preferable to leave any academic treatment of the subject as it has long existed: in a vast array of smaller ventures into regions, periods, and individual artists that make no real attempt at forming a universal view of the area as a whole. Even Jacqueline Barnitz, who has spent more than 40 years traveling and researching the history of art throughout Latin America, is quick to describe these dilemmas in the first paragraphs of her own ambitious and painstaking effort, Twentieth-Century Art of Latin America. "Latin America does not have a survey of its modern art like those that exist for the art of Europe and the United States," she begins. This is an obvious problem for Barnitz. It also serves as a major symptom of the larger difficulties that Barnitz faces in her own attempt. To begin with, there is the long-present tendency in American and European criticism to experience Latin American art through inherited, exoticized notions divorced from any real social or historical context. Barnitz is also keen to point out that the region's colonial history has contributed to a lack of unbiased treatment, one that has been "subject to the vicissitudes of fashions and political as well as economic factors outside Latin America."

There's also the large inconvenience of a unified Latin American art not really existing. The numerous cultures that inhabit the land mass spread between the United States and Antarctica are simply far too diverse in their origins and in their formation and development as nations to be considered and studied as a sort of monolith gliding through time. With all this in mind, the existence of a volume titled Twentieth-Century Latin American Art is, at first, confounding. Given these mountain-high challenges, though, Barnitz still puts together a thoroughly sensible and absorbing study of the art to which she has dedicated her life and the multiple forces that shaped that art.

Studying just one medium of art in just one country might appear to be a simple affair in comparison to Barnitz's work. But Olivier Debroise, whose Mexican Suite: A History of Photography in Mexico presents a fascinating study of the nation's rich camerawork, faces problems of an entirely different nature in his own research. Consider, for example, the fact that not until 1977 did Mexico officially address its photographic history as something worthy of the title and examination of art. Even at that point, it remained unclear what exactly was photographic art and what was just a photograph. In his attempt to pull together a cohesive history of the country's photography, Debroise has had to ask himself that very question time after time while sifting through thousands of assorted Mexican photos.

Like Barnitz, Debroise reaches far back into history to examine the roots of his studied region's art. Making the case that photography in Mexico has always been distinct from that of the rest of the world, he mentions the tale of the 1531 apparition of the Virgin Mary to the Aztec peasant known as Juan Diego. The importance of the tale itself is crucial to Mexican history and the country's image of itself as a blend of Spanish and native cultures. When Juan Diego asks the Virgin for proof of her appearance, she puts a cloth to her face and hands him the imprint of her features. "She prints herself photographically on the cloth," Debroise writes. The Mexican notion of photography and the Mexican notion of identity, then, both begin with what is considered a miraculous act.

Barnitz need not reach as far back for the scope of her work, but she does well to describe the undercurrents of Latin American art and its relationship to European works in the decades before the 20th century. She chooses the dominance of a style called modernismo as a starting point for some of the trends that dominate the region's art at the outset of the century. Not to be confused with modernism in America and Europe, modernismo is a broad term describing the growing need in Latin America for a language and medium that express an awareness of a distinctly Latin American existence. Originating in literature, the basic frustration at the heart of modernismo is perhaps best stated by one of its leaders, the Nicaraguan poet Ruben Darío: "I seek a form that my style can not discover,/a bud of thought that wants to be a rose;/it is heralded by a kiss that is placed on my lips/in the impossible embrace of the Venus de Milo."

The conflict Darío displays between the need for an independent regional identity and an affinity for European art is characteristic of the modernismo movement as a whole. In her text, Barnitz even makes a coy reference to the critical work of the very European Charles Baudelaire by calling these artists "the painters of modern life." While this line may be nothing more than a literary nicety, it does lead to further elucidation about the character of the modernismo movement, and thus the forward thrust into the early decades of the past century of Latin American art.

In his essay, "Le peintre de la vie moderne (The Painter of Modern Life)," which provides a sense of what distinguishes the art of the modern era, Baudelaire lays out rules that echo throughout the work of the Latin American artists and Mexican photographers in both of these volumes. Chief among these is the need for attention to the present as opposed to classical models of art: "The pleasure we derive from the representation of the present is due, not only to the beauty it can be clothed in, but also to its essential quality of being the present." Additionally, Baudelaire further motivates the modernismo movement with his statement that "The crowd is [the artist's] domain."

What these edicts mean for artists in Latin America at the start of the 20th century is clear: The focus shifts to issues and images present in the region. The works that come out of the modernismo movement display traces of French symbolism, true, but they are also the products of new urban growth, cosmopolitanism, class formation, and independence. Barnitz dazzles with her exploration of these themes in their historical context, as she does with her selections of images. For instance, Saturnino Herrán's 1916 work El rebozo (The Shawl), takes a European stance by depicting a bare-skinned woman offering a piece of fruit to the viewer. The classic European lines and color of her face, though, are augmented by the mysterious sombrero at her feet. Barnitz points out that the hat suggests she is in the intimate presence of a Mexican man, and this blend of Old and New World elements creates an aesthetic not unlike those explored by poets like Darío and the Cuban Jose Martí.

New schools of thought and practice come with the following decades, of course, but the main tenets of modernismo, if not their techniques, represent ideals that persist in the painting and photography of Latin America to this day. Take, for example, the photography of Edward Weston and Tina Modotti presented in Debroise's study. Their most remarkable works, dating from the 1920s, serve as icons of the Mexican character. Modotti's photo Campesinos Reading "El Machete" is an unassailable example of the artist using the crowd as her domain. Using an overhead vantage, the photographer captures a group of peasant workers huddled around a Spanish Communist newspaper whose headline reads, "Toda la tierra, no pedazos de tierra! (All of the land, not parts of the land!)" Her attention to the issues and people of her present tense are balanced by the rustic grace of the peasants' hats and the geometric arrangement of their stance. Additionally, she and Weston round out their body of work with several striking still life photographs that follow Baudelaire's assertion that beauty combines what is present with a notion of the unending past.

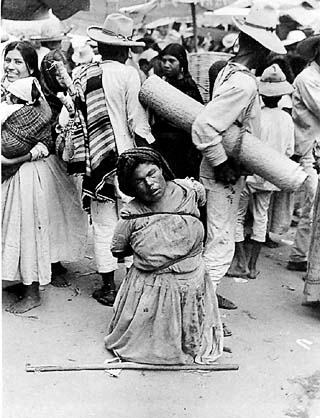

Debroise is far more comprehensive in his approach to these works, though. While they may reflect some persistent ideals of modern art as exhibited by Baudelaire and the artists of modernismo, their photographic nature also brings into play other factors. First, photography is much more easily used as a weapon for social critique, and in some cases, propaganda. When Modotti presents that face of a peasant, she has not created the image as an argument of theory or historical tradition; instead, she is issuing a form of reality that demands a reaction from its audience. Mexican photography heightens this phenomenon with its recurring usage of real figures. Debroise places this Mexican tendency toward the documentary and the nonmanipulated image at the center of the struggle to define what is artistic and what is not throughout the history of the nation's camerawork.

When the leaders of Mexican culture convened in 1977, after all, to discuss the possibilities and expectations of their nation's work, they saw their photographic history as a tool that would "force confrontation with European and North American influence." This is where the powers of painting and photography differ in Latin American art. While the modernistas forged an independent identity by combining elements of European art with new tropes from their own lands and lives, Mexican photography was able to use its own body and land to argue against artistic traditions in an entirely new language. While techniques and perspectives in Mexican photography may share similarities with photos from America and Europe, its subject matter is by necessity unique.

Another movement that Barnitz explores is the wave of art known as "indigenismo." Generally used to describe art depicting the lives of native and indigenous classes in countries like Mexico and Peru, the term has a more extensive meaning that Barnitz expertly details. While much of the art of the indigenismo movement includes pre-Columbian motifs and native subjects, its real aim is to find a national identity rooted in its history. For a country like Mexico, that search often leads to explorations of Aztec and Mayan cultures, but in countries like Argentina and Brazil, the search leads to much different forms of expression. An interesting fact of indigenismo is that even as it occasionally portrays native subjects, the leading artists of the movement tended to be from the nonindigenous upper class.

Perhaps the most famous and resonant art to include early elements of the indigenismo movement (though Barnitz classifies them as the "avant-garde movement") is the work of the Mexican artists Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, Jose Orozco, and Rufino Tamayo. Barnitz's classification is appropriate, as the painters' early work grew out of European travels and studies that introduced them to such ideologies as cubism and futurism. Indeed, Rivera's early paintings, such as Paisaje zapatista (Zapatista Landscape), display an undeniable kinship with Picasso and almost no indication of the epic murals that would come later.

The Mexican mural movement is a fascinating case of government-funded art that Barnitz explores in great detail and lucid language. The undertaking from the perspective of the Mexican government was fascinating -- the goal was to transform the aesthetic of the country to promote the unstable post-revolutionary government as the natural outcome of a centuries-long progression. As any visitor to Mexico City can easily see, that transformation has occurred. Expansive and brightly colored stretches cover buildings from hotels and government palaces to the towering library of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (truly astounding to view). What the government could not anticipate was the social and political growth that the muralists would spur. As many know, Rivera became one of the leading proponents of Marxism in Latin America, and with his growing fame came a more prominent voice on the world stage. Any harmony between the Mexican government and the muralists was short-lived, as most of the painters ended up leaving the country for various stints to create their art in less oppressive environments.

The final triumph of Barnitz's work is that she is able to present the complex issues of artists like the muralists and their contemporaries (among them the overanalyzed icon Frida Kahlo) in a manner that is both comprehensive and digestible. She is also careful to place these currents within their temporal and political contexts. For example, there is no blanket discussion of Kahlo's superb paintings without equal discussion of the painters Remedios Varo, Maria Izquierdo, and Leonora Carrington. Their work, too, reflects much about the social climate of the time as well as removing Kahlo's topics from the realm of the intensely personal to one of more universal discourse. Similarly, Debroise's work is adept at providing a chain of frameworks that is infinitely useful without attempting to be a fluid and all-inclusive continuum of artistic progression. The works of Mexico and Latin America splinter into so many directions and fall out of so many differently colored skies that it would be a mistake for either academic to take such a futile approach. What they arrive at instead, like the most chaotic of the Mexican murals, is a body of work that is crammed full of dissonant faces and lives while telling a seductive tale in numerous and curious tongues. ![]()