Writing in Tongues

The Art of Translation

By Belinda Acosta, Fri., Jan. 12, 2001

There is an episode of the former NBC sitcom Mad About You in which Paul Buchman (Paul Reiser) promises to meet a translator and escort him to a reading featuring a celebrated but little-known Chinese poet. He makes this promise to his wife Jamie (Helen Hunt), whose injured back prevents her from doing it herself. The translator is the only person who can understand and translate the obscure dialect the poet speaks and writes. Paul sets off on his errand, but is sidetracked, looking for an obscure (there's that word again) Italian bakery that specializes in hand-dipped, chocolate-covered strawberries. He is obsessed with buying some for his wife, since he caused her back injury. In spite of Paul's good intentions, and because this is a sitcom, he fails to meet the translator. In the closing moments of the episode, Jamie is propped up in bed with Paul, dumbfounded as she watches the reading on TV. Her husband is translating for the poet (did I mention this was a sitcom?). Just as Jamie begins to scold her husband, he stuffs one of the succulent strawberries into her mouth. Another happy ending.

Perhaps it seems strange in a piece about translation to spend so much time talking about television. But if television offers, as I believe it does, a gauge of the popular perceptions of larger issues -- in this case, the foreign and especially the non-English-speaking world -- this is as good a place to start as any.

On television, and especially in sitcoms, foreignness -- the Chinese writer, the peculiar translator, the oddball family friend who follows the work of the Chinese writer and quotes slightly absurd literary allusions from the writer's work (which Paul works into his "translation"), and later, the temperamental Italian baker -- are presented as something difficult to fathom, and once encountered, decidedly strange.

The final image of the couple, cozy in their bed, their sweets spread before them, is a good way of describing how many in the United States feel about all that is foreign: It's fine at a distance, or if it means getting something yummy to eat. Although Paul Reiser's performance is charming, there is something not quite right about how his role as "translator" is treated as something laughable and unnecessary. Nothing, in this day and age, could be further from the truth.

"According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census," Barbara Wallraff writes in her article, "What Global Language?" in the November issue of The Atlantic Monthly, "ten years ago about one in seven people in this country spoke a language other than English at home -- and since then, the proportion of immigrants in the population has grown. ... Over the same decade the number of speakers of Chinese in the United States grew by 98 percent. Today, approximately 2.4 million Chinese-speakers live in America, and more than four out of five of them prefer to speak Chinese at home." Perhaps some of those 2.4 million Chinese-speakers even watched Mad About You.

Here in Texas, as in much of the Southwest and Florida, bilingual education, access to human services for non-English-speaking immigrants, and other language-centered issues have created bitter debates. And though English is touted as the "global language," the language of commerce and political wheeling and dealing, as Wallraff notes in her article, it is hardly the prevalent language in the world.

Which means that there is potential work for a legion of freelance translators who live and work in Austin. There are many types of translators: literary, technical (medical, legal, high tech), and some who only translate work from English into another language but never in the other direction. Others translate from another language into English but never vice-versa. There are some who translate in "both directions," say between English and Spanish. Some prefer to work with the fiction of authors who are no longer living. Others translate the fiction of living authors who work side-by-side with the translator, or at least have their eye on the process. Whatever the approach, one thing is clear: There is an art to translation.

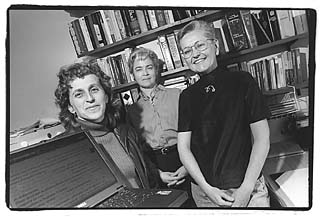

Different Minds

"Different people's minds work differently," Liliana Valenzuela explained quite simply when asked why she chooses to translate from English to Spanish. She rarely works in the other direction. For Valenzuela and other translators, it's a matter of choice as much as natural inclination. A Mexican-raised poet now living in Austin, Valenzuela translates literature and some technical documents. Her translation work includes Sandra Cisneros' Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (El Arroyo de la Llorona), several children's books, and brochures for art exhibits, textbooks, and test materials for the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills. She is also a member of the AATIA (Austin Area Translators and Interpreters Association; www.aatia.org). It's an eclectic, high-spirited group, if meeting with only three of its members at a local coffee shop late last year is any indication (there certainly seemed to be more than three of them). Other AATIA members in attendance included Marian Schwartz, who translates from Russian into English, and is currently at work on a new translation of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina; and Maria "Ria" Vanderauwera, who translates technical documents in both directions from English to Dutch. Arturo Salinas, a professional composer from Mexico, who enjoys translating poetry and songs from Mexican-Indian languages into Spanish, was visiting Austin as a guest lecturer at the University of Texas and participated in the energetic discussion.

The work of a translator goes far beyond simply understanding words and grammar in one language and translating it into another. Translators, in a very real sense, must be cultural guides, social chameleons, and diplomats. To illustrate the spirit of what it means to be a translator, Valenzuela has a line drawing of the Mexican interpreter Malinche on her résumé. Malinche was the subject of Valenzuela's dissertation, but more importantly, Malinche had a way with words.

Malinche was the Indian slave, translator, and mistress of the Spanish conqueror Cortés. She has been fiercely maligned in Mexican history for her role in the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521. Because she had children with Cortés, she's often referred to as the Mexican Eve, though in less polite language. But Valenzuela, along with other modern-day scholars, feminists, and translators, have re-visioned Malinche and claimed her as their own.

"I admire her because she knew her native Nahuatl, later learned Maya, and quickly learned Spanish. I think she must have been incredibly smart to not only learn three or more languages fluently, but also to speak eye to eye with the conquerors, the chieftains, and the kings of all the indigenous nations ... while excelling as an interpreter, guide, strategist, negotiator, and political go-between. The indigenous people considered her one with Cortés, and [she] is often represented as a duality with him. They thought of her as his 'tongue,' another word for interpreter," Valenzuela said.

"Every culture has its own aesthetic," Schwartz said. "For example, from Russian to English, it's necessary to make the text accessible to the English reader while keeping the flavor of the original. To the English-speaker, a direct Russian translation would sound over-dramatic, overstated, and repetitive. English tends to be understated and favors condensation," she said. "The task is to find the strengths of each language; to hear the 'voice' of the original author and re-create that 'voice' in English."

Capturing the intent, and more importantly the cultural context, takes a great deal of skill. Sometimes the smallest word can cause an entire day of head scratching and consulting with other translators.

"Concepts may exist in one culture, but not in others," said Esther Diaz, a bi-directional translator who works with medical texts in English and Spanish. A co-founder of the AATIA, she's taught classes on translation at Austin Community College.

"Take the word 'geek' for example, or 'nerd,' or 'jock.' Those words are so much a part of our culture, but it may be difficult if not impossible to find a similar word or concept in another language. When you get into things like sayings -- "a rolling stone gathers no moss" -- translated into Spanish, it wouldn't make sense. In other cases, there are some things in Spanish that have similar meanings in English. The goal is to find footing in both cultures," Diaz said.

Technical translation poses a different set of challenges. While the aesthetics of a technical text are not at the forefront of the technical translator's mind, accuracy and style are.

"In technical translations, you cannot afford mistakes," Ria Vanderauwera said. As a translator of manuals for medical devices, software interfaces, and other instructional material, precision in language is paramount.

"I'm not worried as much about cultural flavor, I just need to give the information. But, between the Dutch and English, there is a different style in giving instruction. English tends to be flashier, a style the Dutch do not swallow."

Capturing and understanding the technical nomenclature is also of utmost importance. Fortunately, for Vanderauwera and other translators, a host of Internet sources provide opportunities to check sources and discuss translation conundrums with colleagues from all over the world. The AATIA alone has several sub-groups defined by language, genre, literary or technical, and other areas of interest.

Learning the Ropes

How translators get into their line of work seems to be as varied as the translators themselves. While there are few formal programs offering training in translation in the U.S., many translators go through a grueling process of getting accreditation from the American Translator's Association. (Vanderauwera attended a translation school in the Netherlands.) The ATA test includes translating three out of five passages within a three-hour period, by hand. Two trained graders evaluate the work, and if they agree on the result, the translator receives accreditation. It is not uncommon for aspiring translators to fail the first time out.

Although a degree in translation is not required to practice translation in the U.S., "some organizations are now requiring some proof of accreditation," Diaz said. As a consultant, Diaz now travels around the country training medical interpreters on how to communicate with non-English-speaking patients. The request is in response to a nationwide discussion of the need to comply with Title Six of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which provides for clear and accurate information about health care, in addition to the care itself. It's work Diaz finds very satisfying because she knows accurate and understandable information about health care can literally help people's lives.

For translators of literary texts, the benefits seem less tangible.

"In the past, some of the poetry I saw translated was done by anthropologists or linguists, who did not have an ear for poetry. I knew I could do better," Salinas said of his translation projects. In addition, working with another writer's work, or having another translator translate your work, as Valenzuela has experienced, provides opportunities to "hear" the work in a new way.

"It is not only a pleasure, but also much more rewarding -- and in some ways easier -- to translate good, to say nothing of great, literature," Schwartz said.

But perhaps the true gift of the literary translator is in the desire and ability to bring a piece of work to an audience that would ordinarily not have access to it, to bring the literary treats of one culture to another reader's lap, bedside, or desk, and have them savor it in the same way a reader of the work in its native language might.

"It used to be that people could live in ignorance of one another, but in the 21st century, it is going to be necessary to have one foot in each culture, in order to have a true understanding of each other," Salinas offered. "As translators, I believe we have to do what the Navajo call 'speaking in between the languages.'" ![]()