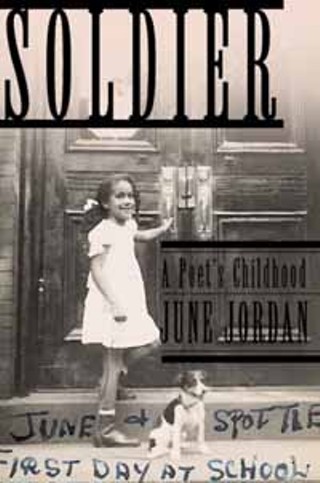

Soldier: A Poet's Childhood

Reviewed by Craig Arnold, Fri., Aug. 25, 2000

Soldier: A Poet's Childhood

by June JordanBasic Books, 261 pp., $20

Poets, we like to think, are pacifists at heart, but their lives often give the opposite impression. In his youth, the Romantic poet Wordsworth was famously enamored of Napoleon, and entertained dreams of becoming a great general. As he recounts in The Prelude, his epic autobiography of childhood and adolescence, the poet discovered his true calling only after his military ambitions were soured by the ruthless compromises of real politics.

Anticipating Freud by a century, Wordsworth's poem traces how the poetic imagination may be shaped by the redirection or sublimation of violent desires and fantasies. It's a model that poets still find attractive, as evidenced by Soldier, June Jordan's reconstruction of her own childhood in the 1940s. A noted essayist on race relations as well as a poet, Jordan is as committed to political activism as she is to art. Her emerging sense of herself as a "warrior," of being armed and toughened up for a battle, colors every episode of her childhood, from her early memories of the Harlem housing projects to her coming-of-age in a more upscale Brooklyn neighborhood -- a "great big painting of a new life that never fit inside its frame."

Jordan's war is domestic and civil, a pitched battle between the conflicting ambitions of her West Indian immigrant parents. Her father, overbearing in both affection and severity, seems to want quite literally to make a man of his daughter, and an educated white man at that; he beats her, without mercy and often without warning, for behaving like a "damn black devil child." Her long-suffering mother, on the other hand, sees her daughter as a modern prophet, "a great help to her people." At times, Jordan's parents feel more allegorical than real, mere mouthpieces for the poet to articulate her more mature perspectives on class and race. Still, her primary interest is the dynamic and dynastic struggle of a family drama. As she puts it, "I had become the difference between them."

Such muscular plain statements are Jordan's strength as a poet, but they don't feature prominently here. Jordan is also a professor (at Berkeley), and her writing style reflects an academic's self-consciousness, a syntax put through a variety of gymnastic routines. Paragraphs breathlessly unbroken by punctuation are backflipped into one-liners that owe as much to the clipped delivery of children's fiction as to the verses of the Old Testament. At its best, the shape-shifting narrative possesses the ingenuous goofiness of a child's viewpoint, the sound of little mouthfuls of experience being bitten off and chewed. At times the wandering right-hand margin seems a bit contrived, an adult's studied imitation of a kindergarten crayon drawing. Jordan is quite adept at enlisting the devices of poetry or fiction without such distraction. Take, for example, her account of a deep-sea fishing expedition with her father, intercut with a family outing at the beach. The counterpoint between the two episodes is superbly suggestive; although less cutting-edge, it's eminently more satisfying.

Deliberately sketchy, Soldier is the portrait of an activist-in-the-making: self-assertive and scrappy with a taste for violence. As Jordan muses at the tender age of four, "a really excellent way to stop somebody from hitting you is to hit them back." She seems less interested, however, in communicating her affinity for language, for its "regular feelings of agreeable intoxication." In one passage, "the split between religious and regular words disappeared": An accidental rhyme between "merrily" and "verily" sends Jordan into a fit of giggles, as the child discovers the pleasure and power of messing around with the significance of words. Elsewhere Jordan captures the sense of dissociation or detachment from conscious experience that most poets experience. "I developed a way of dreaming all of the time, no matter what," she writes:

I could even talk or listen and keep on dreaming.It wasn't so much a dream about anything.

It was more like staring at a stain on my mother's apron and then not forgetting that stain as I walked to school or went out to play.

But Jordan's love for poetry, for its particular focus of attention, is as ambivalent as her love for everything else in her childhood, and such flashes of insight seem almost uncomfortably hidden.

In the end, Jordan is her father's daughter, inclined more toward action than introspection, and although she tries to strike a balance, it's her father who dominates the account. His boundless energy, his pungency of speech and gesture, are related with obvious relish, and loving attention to detail, whether he is stringing a clothesline, or simply eating a grapefruit over the sink. In contrast, Jordan's dutiful sensitivity to the stained apron, to her mother and all that she represents, looks tiring and uninspiring.

Like Rilke, whose mother dressed him as a girl for most of his early years, Jordan's story supports our intuition that poetry begins with bent gender, with the tomboy as well as the sissy. If Wordsworth's poet is a failed warrior, Jordan's is a successful one.