The "Master of Disaster"

By Clay Smith, Fri., June 4, 1999

|

|

In 1971, at the age of 26, Cuny founded Intertect (short for International Technical Consultants in Emergency Management) in Dallas, where he grew up. Cuny's goal was nothing less than to institute a "radical restructuring of the way the disaster relief system operated throughout the world," Anderson writes. That self-directed edict took Cuny to Managua, the capital of Nicaragua, in late 1972, when a powerful earthquake killed some 6,000 people and left many more homeless. It took him to disasters the world over: in Guatemala, Sarajevo, Somalia, Kurdistan, and, finally, to Chechnya. In that time, Cuny became something of a boon and bane to the disaster relief community. He could be turned to for directions not only on "how to signal a helicopter in an emergency landing, or the best urinal design for the tropics, or how to thatch a roof when only short-stem palm fronds were available" but also for less practical advice, like insight into warring factions or why the color of a tent in a refugee camp might offend a refugee. But if Cuny was a source of knowledge for the disaster relief community, he wasn't necessarily loved by that community. "He wasn't there to ingratiate himself with the disaster relief fraternity, but rather to give it a good spanking and then reform it," Anderson reveals.

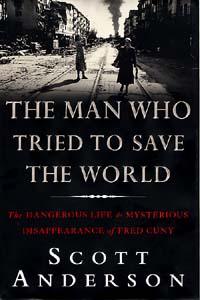

Though Anderson's portrait of Cuny is favorable, it's clear from The Man Who Tried to Save the World that Cuny was a complex, even self-aggrandizing, figure. After Cuny disappeared from Chechnya, where he was dispatched by financier and philanthropist George Soros' Open Society Institute to assess the level of damage in Chechnya's war for independence from Russia, news reports of his disappearance regularly featured Cuny as a "larger-than-life figure, a swashbuckling Texan with a renegade streak." Fiercely ambitious, Cuny chose work over family again and again, which in his case meant that he had a mostly detached relationship with his one child Craig Cuny, who now is grown with a child of his own, and who lives in Austin. Anderson, who has made his name as a journalist covering war zones, is a contributing editor at Harper's who writes frequently for The New York Times Magazine, and is also the author of a war novel published last fall, Triage. "The first war I went to was Beirut in 1983 before the Marines got blown up and of all the 15 years I've been going to war," Anderson says, "there have been five times in my life where I really thought I was going to die and three of those five happened in Chechnya, in two and a half weeks." He has said that he writes primarily from images rather than from other literary catalysts. I was curious how the impetus of images worked in the case of a subject like Fred Cuny, who had disappeared (and is presumed dead) before Anderson even began working on The Man Who Tried to Save the World.

Scott Anderson: In this book, I felt a bit ham-strung. At least what I tried to do with this where possible was to kind of tell stories, maybe the most in the chapter where I talk about Kurdistan and Somalia and Bosnia. I think that's one of the things I chafed under a bit with this book, frankly. If the story had been simpler, I think I would have written it in a different way. But because it was so complex, both what happened in Chechnya and his life, that it kind of imposed a rather traditional journalistic approach.

Austin Chronicle: You dedicate The Man Who Tried to Save the World to Craig Cuny and you consider him a friend. While writing the book did you wrestle with that journalistic axiom that forbids you to get too close to a subject?

SA: Well, it's funny, I'd never really gotten close to a subject before and it created for me, I think less so for Craig, it created a lot of weird issues because I didn't want to trade on our friendship to get access and what actually ended up happening was that for about a year and a half I kept coming down to Austin for like a week at a time to hang out with Craig and I'd leave New York and I'd always say, "Okay, this time you've got to interview him. Just sit him down for five or six hours and get it all on tape and then you'll be done with that." And there were probably about six or seven trips that I came down to Austin and instead we just drank and played and I got back on the plane to go to New York. It went on for like a year and a half. And finally the only time Craig and I -- we didn't sit down -- we talked on the telephone about five or six months ago when I had a semifinal draft and we spent about three hours on the phone going through stuff and for me it was just a very strange thing, that whole journalistic thing the way you would ingratiate yourself with people and pull confidences out of them and because of the friendship with this, it was very hard for me to do that. ... The thing is, we never talked about his father. Craig doesn't like to really talk about him and I think that it's not so much what I said because it's a very favorable portrait overall of Fred but I think what had to have weirded him out is that here's a guy who's a friend of yours but who's just been so analyzing of your life and your family chemistry the last two years. I think that would have to be a weird experience.

AC: The idea of Texans being larger-than-life plays a pretty prominent role in the book, and Fred Cuny proudly wore that badge. How did that influence his relationships with people in war environments?

SA: Everybody I interviewed, all said that within 10 minutes of meeting Fred, he let everyone know he was from Texas. ... He would use being from Texas the way people would say, "Well, you know, I have a Ph.D. from Harvard." ... He used the fact that he was from Texas as this authoritative credential.

AC: One of Fred Cuny's high school friends speaks of him as never being conscious of limitations. Did you sense early on in this book that that element of his personality might lead you into a never-ending morass of investigations?

SA: I'm not sure I wholly agree with that. I think he did [have a sense of limitations]. The thing that I think is particularly poignant about the story is that when he went back to Chechnya the second time, this kind of toss-off explanation that his friends and colleagues gave was that "Well, Fred had been doing it so long that, you know, maybe he just didn't think that anything bad could happen to him." And that has run opposite to everyone I know, including myself, who gets into situations like this -- that the more you're exposed to combat, that in fact the more cautious you become, the more frightened you become. And I think Fred was very clearly frightened going back to Chechnya a second time and yet went anyway. He had been involved in a lot of situations over the years ... and he charmed his way out of it. He was incredibly charming, this big ol' Texan who could find a way to deal with most people. A very sort of personable, affable guy. And it had always put him in good stead, and in Chechnya, that stuff just didn't count.

Scott Anderson will read from and sign The Man Who Tried to Save the World on Thursday, June 10, 7pm, at Book People.