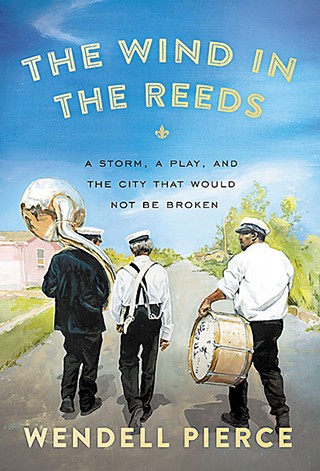

Wendell Pierce's The Wind in the Reeds

In this memoir by the actor, Godot and Treme help transform post-Katrina New Orleans

By Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 16, 2015

Maybe you thought of Treme as just another HBO show – the thing David Simon did after wrapping The Wire. Maybe that's all it was to you, but to Wendell Pierce, Treme was personal.

Just how personal is made crystal clear in The Wind in the Reeds, a memoir penned by Pierce about his life in New Orleans. The actor, who played Baltimore detective Bunk Moreland on The Wire, writes in great detail and eloquently about his family's deep roots in that city's swampy soil, his growing up there, how his family was affected by Katrina, and his decision to re-establish a home there after a profound artistic experience: performing Waiting for Godot in the streets of the Lower Ninth Ward for survivors of the storm. No set designer could concoct a setting as close to Samuel Beckett's desolate landscape as that one. Pierce wanted to be part of the rebuilding of his hometown, and Simon ended up coming with him, creating a new series about the Crescent City in the wake of Katrina's devastation. To be able to use his art to tell his city's story as it was rebuilding was, Pierce writes, a gift.

Austin Chronicle: In the book, you thank so many people in your life: your grandparents, your parents, other relatives, David Simon, actors you worked with. Did you set out knowing that you wanted to do that?

Wendell Pierce: No. That was unexpected. What I wanted to do was talk about an awakening of sorts, a reminder I received about the transformative nature of art. And [that led] me to a reminder of the power of the art in New Orleans that was a part of the culture as I was growing up. It reminded me of the sacrifice so many people made – for me, in my community, what my community was all about – and that the resilience I was searching for as a result of our city being destroyed was already in the DNA of the legacy of family and folks who had come before. It was a rediscovery of the values that were passed on in the character of the men and women who had endured what was even worse than anything I was going through with Katrina. It also made me wake up to where that resilience within them came from, and that led me back to art, how art can be the realm in which we collectively reflect on who we are and where we're going. And it all came from this one cathartic moment in Waiting for Godot.

It was the same production we had done at the Classical Theatre of Harlem immediately after the disaster. That was amazing because, without changing [any lines], to have a stage flooded with 15,000 gallons of water, with a rooftop coming out of the middle of it, Estragon sitting on its apex, and [me making] an entrance wading in water up to my chest, I realized that it was a play that resonated to what was happening in New Orleans. And when we got the opportunity to bring it to New Orleans, to the hallowed ground where many people had lost their lives, where in every direction you looked it was nothing but destruction and desolation, it was profoundly cathartic. To do that play with a collection of people from all walks of life, from New Orleans and outside the city, who understood that when I said, "All mankind is us. At this place and this moment in time, all mankind is us. Let us do something while we have the chance," it was an epiphany. It was the thing that made it clear that we could not wait for that outside of ourselves like Godot, that we had it within ourselves to do something, and we had to do something or we would be gone.

AC: You cast that play in a more hopeful and positive light than any production I've ever seen or read about. I try to wrap my head around what it was like actually doing it in the city for all those survivors ....

WP: But even more importantly, know that we literally were on the ground where hundreds had died, that, as survivors, we knew we owed a debt to them to not forget the awful end to their lives that they had to endure; that we had to, out of respect for their loss of life, rebuild a community – in essence, it would demean their death if we just said, "Hey, let's give up on this place." What it was was a call to action and an appeal to your humanity. "Let us do something while we have the chance. All mankind is us." Whether you like it or not, we have that in common, and that was the poetic truth of the disaster of Katrina.

People of goodwill came from all over the world to help us. And we knew we'd need every person and every ounce of strength because there were going to be those who didn't have our best interest at heart, who said he sees this as an opportunity to change this city "demographically, geographically, and politically," as James Reiss said in The Wall Street Journal only a week after the levees broke. When I saw that, I was like, "You know, this is not new." So much of our culture comes from fighting that battle. Social aid and pleasure clubs – we all understand the pleasure part: a good parade, having fun, good music. But the social aid part we forget. That was a social safety net for those who were denied insurance because of segregation, Jim Crow laws, couldn't get a burial plot, redlined areas. We pooled our money in social aid and pleasure clubs to make sure people were taken care of. Your mom or your dad died? We're gonna send 'em off with a jazz funeral to honor their life. That was culture in its most profoundly impactful form. It's not just entertainment. Art is not that frivolous. It is important.

Our culture is where we intersect with life. I realized that it goes back even further to the creation of jazz, captured Africans who found their freedom in their creativity before they found their physical freedom. Took the African Duh-duh-duh-da-duh-duh, combined it with the brass music of their oppressors: oom-pah-pah, oom-pah-pah, and turned it into: bomp-bomp, de-boda-bomp-bomp-bomp. Jazz, you know? Freedom and individuality, improvisation within structure and form. We are a nation of laws, but you can find your individual potential within that. That's the American aesthetic.

And that came from culture. And we lived our culture in New Orleans more than most places I know. That was the epiphany I had within the play. The storm that produced this play that produced this epiphany that reminded me of the legacy of my community and family that would not be broken.

AC: Was Treme a continuation of that ability to make a difference with your art?

WP: Absolutely. Actually, Treme was like group therapy. Around the city, people would reflect on where they were two years ago, and in the midst of their despair and depression and whether the recovery was going fast enough, they were able to look back and see: "Well, maybe I've gone a little further than I thought. I won't give up. This encourages me to go on." Look at how we honored what was going on in the culture. It was in that form of art that we found our relatives and reflection on where we'd been. Like thoughts are to the individual, art should be for the community. Treme served that role and bolsters that belief that I have of the transformative nature of art.

Wendell Pierce will speak about The Wind in the Reeds at the Texas Book Festival Sat., Oct. 17, 4pm, in the House Chamber of the Capitol, 1100 Congress.