Such Stuff as Screams Are Made On

Austin punk gets the museum treatment, but does the scene come off as dead or alive?

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., March 20, 2009

The sound is what hits you first: guitars in full thrash mode, a furious jackhammer drumbeat, and, bodysurfing on top of both, a voice that's screaming more than singing. It's raw and urgent, and it's there the instant you open the door at Arthouse, your raging musical introduction to a museum exhibition about punk rock in Austin.

As there's something dangerously oxymoronic about punk rock in a museum, no matter how contemporary it may be, the presence of that pounding soundtrack is somewhat reassuring, a signal that this institution hasn't completely drained the subject of its red, raving vitality and just propped up the embalmed corpse of punk for our academic scrutiny and appraisal. Though, in most of the gallery, this music isn't as loud as punk should be – only because it's really just sound bleed from the gallery where a film is running on a loop – its propulsive energy still gives you the confidence to dive into this investigation of the local punk scene by a Brit, rising art star Matt Stokes.

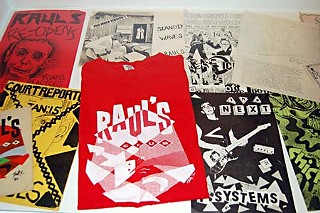

And dive in is pretty much what you have to do with "Matt Stokes: these are the days," because its creator has provided the viewer with no curatorial direction, no guidance into or through the exhibition. You'll find no wall text supplying context for the scores and scores of objects he's assembled from three decades of Austin punk, no annotations for any of the items themselves. For the most part, you just get shelves and shelves of CDs, fliers hanging on the walls, and glass cases packed with zines, T-shirts, videos, and print articles laid out without any overt sense of organization. It's as if you've stumbled into the bedroom of a longtime fan of local punk, one who's been compulsively collecting and preserving everything about it for years and now has all this stuff that he keeps on display for his own gratification, organized according to some internal logic that he doesn't need to explain. Maybe Stokes is deliberately evoking that fan-ish devotion, with its powerful personal bonds to a subject and its impulse to acquire and be comprehensive, as a way of linking the exhibit with the spirit of the scene it describes, one launched with intensely personal passions and sustained by them. Or perhaps he just wants every visitor to make his or her way through the exhibit and draw meaning from it without direction from a curatorial authority. In other words, Do It Yourself.

My path started with the display case directly to the right of the gallery information desk, where I found myself confronting what might be considered the Big Bang of Austin's punk scene: the appearance of the Sex Pistols at San Antone club Randy's Rodeo in January 1978. The gig, one of only seven dates the band played in the U.S., exploded into a riotous face-off between band and audience, and the effect on the Austinites who attended – and even those who didn't attend – was profound. A feature in the Austin Sun told the story, and a copy of it is included under glass here and can be read almost in its entirety. It's one of the canny ways that Stokes gets around having to articulate Austin punk's history himself: Alongside the historical posters, fliers, and albums on display, he sets old newspaper stories that are themselves historical documents and that tell the story of the scene for him from a contemporaneous perspective. Turn the corner to the right of that case, and you'll find newspaper accounts of the first major punk controversy in Austin: the arrest of Phil Tolstead during a performance by his band, the Huns, at Raul's on Guadalupe. Beside it is a monitor showing video about the band Reversible Cords, aka Re*Cords, which got into hot water for making fliers for a concert out of IRS forms. One of the videos is a local TV news report describing the band's trouble with the law and showing them protesting in the Capitol rotunda. Displayed near it are zines and fliers that also address these incidents and the fallout from them. And in other cases you can glean information about the scene and its development in zines such as Contempo Culture, Sluggo!, Peek-a-Boo, Geek Weekly, and Xiphoid Process, as well as in articles from mainstream publications such as the Chronicle. The context isn't missing after all; it's simply layered in among the other artifacts.

Moving around the room, one passes flier after flier for the bands that rose up and raged in this surprisingly fertile soil for punk music (surprising because at the time Austin music's other claims to fame were the hippie cowboys of the progressive country movement and quintessential yacht rocker Christopher Cross). It's an honor roll – dishonor roll? – of our town's hardcore bands: the Dicks, the Skunks, the Big Boys, the Violators, Standing Waves, Terminal Mind, the Next, D-Day, Scratch Acid, Sharon Tate's Baby, Boy Problems, Jerry's Kids, Toxic Shock, Power Snatch, the Hickoids, Gomez ... the list goes on and on. And beneath their no-budget, clip-art-studded, crazily creative handbills are cases dedicated to the places they played, clubs that were instrumental in supporting the punk scene and allowing it to grow: Raul's, Club Foot, Duke's Royal Coach Inn, the Blue Flamingo. They're long gone, as are most of the bands, and for the person who was present for their heyday, the sight of Guy Juke's logo for Raul's or a Club Foot T or a Woodshock flier may inspire the inevitable flutter of nostalgia – a sentiment so antithetical to punk and everything it's always shrieked about that it feels somehow traitorous. And if you recognize that, then you have to ask yourself: Is this what that once-seething, surging impulse has come to? The fact is, the original generation of punks are in middle age now, with kids if not grandkids. The glass cases, the albums in plastic sleeves – it's like we're scrapbooking rebellion. It's punk domesticated, the snarl of the wolf reduced to a whimper.

And yet, that scream is still present – the one that greeted you when you walked in and has been clawing at the back of your ears ever since. Follow it to its source, and you'll find yourself in a dark room facing a two-channel film on a continuous loop. On the left are images from a free, all-ages punk concert at the Broken Neck in East Austin; on the right is a performance by four musicians at Sweatbox Studios. The foursome, all in current punk or hardcore bands but who don't play together, created an original song based on the footage on the left and recorded it in one take. Here you can experience the music at something more like an appropriate volume, the drums like a semiautomatic nail gun firing in your ears, the guitars like redlining engines, Yoshi Okai's vocals like someone furiously ripping up carpet. Their music and the intensity with which they're making it are in striking contrast to the concert images, which concentrate on the audience and have been slowed down slightly, generating a dreamlike vision of this communal experience. As you watch these young people moving in a circle, bumping into one another, tossing back beers, you can glimpse something ancient at work, that kind of ecstatic ritual in which music takes people outside of themselves and also binds them together. But what's maybe more significant is that it's happening now. Maybe what's been collected in that other room are relics of a once-vibrant past now petrified and inert, but in this room is the present. The screams that started at Raul's 30 years ago are still being screamed today at the Broken Neck and in Sweatbox Studios, and they're being heard.

After watching the film, I pass back through the other galleries and, going past all those records and fliers and zines again, am struck by a new sensation: What a prodigious amount of material this is, how many people were active in this scene and how much music and art they generated in a relatively short span of time, and what an impact it's had on this city for more than a generation. The sense of nostalgia may be there, the air of faded glory, but that isn't all there is to it. There was a coming together and a founding of something consequential, something that seeded change that is still being felt today.

I make a final stop at a section focused on Huns frontman Phil Tolstead. On one wall, footage of him and his band is projected. Opposite it is a video monitor playing a clip from The 700 Club in which a born-again Tolstead describes his days of sin and his redemption from it by Christ. It's a fascinating footnote to that first era of Austin punk: its most notorious figure rejecting his past so radically, so publicly. You have to put on headphones to hear the audio from the television clip, and as I was listening, I realized that I could still hear the soundtrack from the film in the other gallery. I was focused on the past, but the present kept bleeding through.

The scream is still here, is always here. Not for nothing did Matt Stokes want us to know these are the days.

"Matt Stokes: these are the days" is on view through April 5 at Arthouse at the Jones Center, 700 Congress. For more information, call 453-5312 or visit www.arthousetexas.org.