Hang the DJ

The new political theatre wants you to join its messy, sexy conversation

By Katherine Catmull, Fri., Jan. 20, 2006

"Theatre gets to create a topic of conversation for a very small audience for a very small window of time. I think we should each use that window to talk about what is dearest to us. If that doesn't include politics at least part of the time, then I probably don't want to hear that conversation." – Austin playwright Kirk Lynn

Burn down the disco

Hang the blessed DJ

Because the music that they constantly play

It says nothing to me about my life

– "Panic," the Smiths

A year ago in London, I saw a political play called, no kidding, Myth, Propaganda and Disaster in Nazi Germany and Contemporary America. I'd read several admiring reviews – Michael Billington in The Guardian called it "fictionally gripping and politically stimulating." The story: A radical Australian professor faces career- and life-threatening danger when he expresses a few leftist ideas in the ultra-conservative post-9/11 milieu of ... a New York City university.

Okay, right away you're saying: This guy is the only liberal on the faculty of a major university in Manhattan? Wha–? But oh my friend, that was only the beginning. The whole thing was so god-awful, my companion and I walked out at intermission. Translucently thin characters; preposterous assumptions; a hilariously mysterious villain, a Texan (!) in black who materialized at key moments to beat up our hero and be all Kafka-esque 'n shit – it was unbearable. It was unbearable, and I agreed with it!

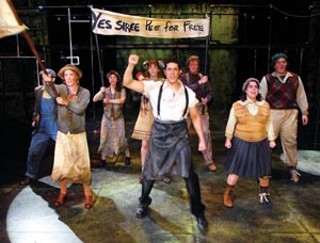

Then last spring, in Austin, I saw the Rude Mechanicals' workshop production of Get Your War On, an adaptation of the brilliant and scathing Internet comic by David Rees. It was hilarious and thrilling. The audience responded with the drunken, desperate laughter of people in a spiraling plane. I left exhilarated.

And these two experiences left me wondering: What is the point of political theatre? Who goes to see it in the first place, anyway: like six people? And isn't "political theatre" usually just a bunch of smug liberals paying to have their own bland idées reçues stuffed back down their throats?

Well yes: when it sucks. But when it's alive, when it's surprising, when it's busy doing its proper job of snapping us out of our cultural trance, then political theatre is right at the heart of the human conversation.

Since September 11 and the start of the Iraq war, we've seen a lot more political theatre in Austin and elsewhere. This week, besides a remount of Get Your War On at the Off Center, the hilarious and ickily-named Urinetown: The Musical opens at the Zachary Scott Theatre Center. So it's a fine time to think about why that is and how local playwrights and artists are finding ways to talk urgently about our world while avoiding the dangerous undertow of pretension and tedium.

All really interesting ideas are shaped like a football

"I have been thinking a lot about bowling and football. I think a lot of theatre gets made like bowling. It has an inevitability that builds but never goes away. [It] sets up the big ideas they are going to try to knock down and then sets about knocking them down. But really good theatre is like a fumble. All really interesting ideas are shaped like a football. When they get loose, there is no telling which way they are going to bounce and the whole contest is up in the air. Political theatre should aim to fumble more." – Kirk Lynn

Is that right or what? How much bowling-ball-shaped art have you seen, rolling dully toward its inevitable end, the only question whether it would knock down its intended pins – "Yay, I guess," you think, dispirited – or gutter uselessly off to the side.

Good political theatre is football-shaped. It should surprise the hell out of you. It shouldn't flatter or comfort. It shouldn't seem like Common Sense or accord with Basic Values. If it does, it's living inside the old trance or creating a new one. Good political theatre doesn't let you escape into some new half-truth. It keeps the walls down.

Under its jokey and proudly juvenile surface, Urinetown slyly subverts every cliché of the Broadway musical and white-hat political theatre. It's unpredictable: and that's key. Steakley notes that at the end of the play, "the good guys win, people can pee for free, and everything starts falling apart. It's a powerful moment handled with great humor in the show, and quite the thing to chew on in a 'blue' city like ours."

Kirk Lynn (whose conversations with me on this topic inform this piece, and who probably ought to have written it, but too bad, I did) is currently in New York City for the opening of his proudly political satire Major Bang (Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Dirty Bomb), produced by the Foundry Theatre at St. Ann's Warehouse. He says political theatre comes down to finding out "how to create a new paradigm which can fracture the onanism of it all and return us to messy, sexy conversation."

And yet

I read that, and I want to reserve my seat for the messy, sexy conversation right this second. And yet ... I was so traumatized by that god-awful play in London. Bad political theatre is so specially, radiantly bad – what's up with that? Ask around, and you'll find playwrights and directors can eloquently finger several culprits:

Preaching to the choir. In a New York Times interview last year, Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner called this "the experience we have all had, sitting in a theatre being told over and over something we already know." (But Kushner also notes that this syndrome is misnamed, since "a good preacher rattles her congregants' smugness and complacency.")One of the few political plays in recent years to be a success with large mainstream audiences, Urinetown "lays out its premise brazenly in the opening song," says Zach Artistic Director Dave Steakley. "'It's the oldest story/Masses are oppressed/Faces, clothes, and bladders all distressed/Rich folks get the good life/Poor folks get the woe/In the end, it's nothing you don't know.' It's very Brechtian to be so forthright; the difference here is the humor with which this story is buoyed throughout."

Evangelism. Austin playwright Lowell Bartholomee says, "If I detect that someone is trying to push some particular message on me, I have a strong tendency to reject it and resent the play." Kushner zeroes in even further, calling these "plays which try to woo and seduce hostile, recalcitrant people, people less enlightened than the playwright – plays of condescension, in other words." Overexplicitness. Steven Tomlinson, the economist and monologist who most recently performed his tender and politically questioning American Fiesta for the State Theater Company last fall, says, "I consider a political play 'bad' when it leaves little to the imagination. When a play 'makes a point' without doing the hard work of finding a compelling metaphor ... that is, without respecting the imagination."(My favorite line in American Fiesta comes after a party in the protagonist's new, more decisively Democratic neighborhood, where people need "constant angry reassurance that you're even more worked up than they are" about the state of the world. The line is "No more one-party parties!" I feel this should be the rallying cry for the new political theatre. That should guarantee some fumbling.)

Idiotic oversimplification. Cyndi Williams, author of the post-apocalyptic and politically charged American Arcana, which has been produced twice in Austin in the past decade (most recently by Refraction Arts Project), says, "The political theatre that enters my personal moan zone tends to be the more black/white, good/evil, Jesus figure vs. bad guys pieces." Recalling a play whose general point she agreed with, she says, "I wanted to strangle those people for giving validation to such simplistic canonization of the noble hero/vilification of vile villain crap! It's the same kind of thinking that Bush indulges in, and look where that got us."Of course, simplistic art can still be politically effective art. Uncle Tom's Cabin is not treasured for its literary quality, but it changed the world – a bowling ball that bowled a perfect game. But that works better in, say, a song. Steve Earle's "Jerusalem" may not repay careful logical analysis, but it moves me and gives me hope. Stretched out over the course of two hours and played out before me with actors solemnly dressed as lions and lambs, lying down together – well, I expect that my head would slowly, slowly explode.

The human conversation and how to squelch it

"I think we live in an era when people are desperately trying to shrink the parameters of dialogue. I think that is the real goal of terror. I think that is the goal of a lot of talk that masquerades as conversation on morality. I think all good theatre should aim to expand the parameters." – Kirk Lynn

And that conversation is something we desperately need. Because just about everything else in our society – in our society, not just Soviet Russia or Iran – is geared to shutting it down and shutting us up.

In the über-privileged U.S., that lockdown takes the form of a cozy, superinsulated trance. Playwright Robi Polgar, whose 2004 The Road to Wigan Pier (on which I worked) translated George Orwell's book about unemployed British miners into a skewed musical-satirical statement on 20th-century political science, observes blackly that Americans "are so insulated, we wouldn't know good art if it walked into a bus and blew itself up."

What political theatre at its fiercest can offer is something like a chance to break out of that insulation, break out of the cultural trance for a bit, to see things fresh and in a much bigger space. Political theatre can dislodge our true conversation from beneath the boulders piled on by terrorists and moralists and a mocking or soothing media.

That's a pretty subversive thing for art to do – to offer what the radically strange British playwright Howard Barker calls "a freedom from the moral consensus" – which may explain why good political theatre is so hard to achieve.

But it's worth it. Exploding the walls of conventional thought produces a deep joy – the joy I saw in the Get Your War On audience, or the pleasure that rippled across the country when Jon Stewart went on Crossfire to say, this show is hurting America, and by the way, Tucker Carlson's a dick.

"That Smiths song 'Panic' kept going through my head, thinking about what I was going to say about this. The line about, 'The music that they constantly play says nothing to me about my life.' That's how I feel about apolitical theatre. What is theatre that's not political? Normal. I hope not." – Kirk Lynn

The mirror slaps you

But it's hard to let go of that sweet cultural trance. The Austin-celebrating Keepin' It Weird, which closed last month at Zach, took a sober turn in the third act, with police department transcripts from the Midtown Live nightclub fire and a frank discussion of Austin's race relation problems. Director/creator Dave Steakley says, "I had a TV interviewer say to me ... that the first part of the play feels like Austin being so self-congratulatory and preening in front of a mirror loving itself endlessly, and then the mirror slaps you."

Good for the mirror. Theatrical alienist Bertolt Brecht put up signs ordering his audiences, "Glotzt nicht so romantisch!" ("Don't stare so romantically!"). Open your eyes to reality, he meant; let go of the misty dream, even the one this play is creating.

Little Sally: I don't think too many people are going to come see this musical, Officer Lockstock.

Lockstock: Why do you say that, Little Sally? Don't you think people want to be told that their way of life is unsustainable?

Little Sally: That, and the title's awful.

– Urinetown: The Musical, Mark Hollmann & Greg Kotis

Of course, there's more to it than kicking down walls. Playwright Steve Moore says, "At its best, political theatre takes the world we live in, lifts it off the ground, and sets it down whole on different pilings." Moore wrote Nightswim (produced by the State Theater Company in 2004), a curious, slightly surreal, and entirely beautiful piece about Roy Bedichek, J. Frank Dobie, and Walter Webb, the three men on Philosophers' Rock at Barton Springs. It is not overtly political; and yet more than one person I interviewed named it among their favorite political plays.

Good political theatre changes the way you see things. Dan Dietz wrote Americamisfit (produced this past fall by Salvage Vanguard Theater), which suggests that, as he puts it, "maybe we as Americans are addicted to revolution, choosing quick, often violent means of change rather than building more slowly on what we have." He says "all good theatre (and good art, for that matter) alters one's perception of the world – even if only slightly. And that includes political theatre."

And Moore adds that "Political theatre that actually succeeds ... makes an effort to rehumanize the conversation."

Why conservatives don't write plays

"Henry Luce, the founder and publisher of Time and Life, was once asked why he hired so many liberals to write for his magazines, given that his own political views were unabashedly conservative. 'For some goddamn reason,' he replied, 'Republicans can't write.' Well, they've learned how, but for some other goddamn reason, they don't write plays." – Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout

Yes: Why is it only liberals? "Because conservatives don't do theatre" just begs the question.

Political theatre, in order to work, must be in some sense subversive. "Tear down the walls!" is not the typical cry of the Republican. Kirk Lynn describes Major Bang as "a conversation between fundamentalism and enlightenment and seeks to give the audience comfort with the notion that there really isn't historically any great fundamentalist – or for that matter, conservative – moment. All the great moments of history are based in enlightenment."

Not that conservatives have a monopoly on rigid thinking. When liberal/progressive thought becomes rigid and dogmatic, then it, too, becomes ripe for satire: thus the sly political theatre of the Soviet era. When American liberals grew staid and self-satisfied, a hundred Rush Limbaughs bloomed.

It's alive

"Someone made a comment at the club, going, 'We don't come to comedy to think.' Gee, where do you go to think? I'll meet you there! We don't have to do this here!" – comedian Bill Hicks

Why political theatre, then? Why not film? Why not TV? Why not Jon Stewart, since I brought him up? Well: I could in fact expand my definition of political theatre to include film and TV (and don't think I won't, if you kids keep arguing back there). But I am interested in what theatre offers specifically that film and TV don't.

TV is a sales pitch. Film is a brilliant, flickering dream. Theatre is living alchemy, and you are one of the ingredients.

It offers the uncomfortable shock (or is it thrill) of any live interaction. It is unmediated. The audience at a play is vulnerable; there is nothing between you and the performers. It's the same quality that makes bad theatre so painfully bad – that raw, tangled-in-each-other's-vibes quality.

But also, and maybe even more essentially, when you get down to it there's not as much money in theatre. Only the most expensive theatrical production costs as much as a modest film. And if you've seen any theatre at all, you know that as the productions get more and more expensive, they also tend to grow more ponderously bowling-ball shaped. Luckily for football fans, there is still plenty of fringey cheap theatre, especially here in Austin.

So go out and see some political theatre. Or better yet, hang the blessed DJ and make some. Something alchemical happens when a bunch of bodies are in a room together: The space turns into a cauldron where juices and ideas and people on both sides of the stage edge are transformed.

Or else it turns into a painful hideous mess, of course; or else, I won't lie to you, nothing jells at all and the ingredients sit there inertly, staring at each other. But when it works, when you can finally admit, "I'm in a spiraling plane," and be grateful and joyful for the news, then there's nothing like it. ![]()