Next Edition

After 13 years of making exquisite prints, Flatbed Press ponders what's to come

By Madeline Irvine, Fri., June 13, 2003

Ink hits paper every day. We sign our names, jot down a phone number, make lists, write in a diary. Newspapers and books are printed. Each resulting artifact has a different life span; grocery lists and newspapers are momentary compared to great books, and signatures on a marriage license or a mortgage live longer than those on checks. Just as rocks and fossils contain much of the history of the earth, the union of ink and paper, whether entered by hand or printed on a press, contains much of the history of the man-made world.

When ink hits paper at Flatbed World Headquarters, it is meant to last, and it is meant to be exquisite. Flatbed trades in images, specifically collectible prints by contemporary Texas artists. It is a fine-arts printmaking press that has been producing some of the finest work of its kind for more than 13 years. Flatbed editions have ended up in several major institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum of Art (work by Michael Ray Charles) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (work by Trenton Doyle Hancock).

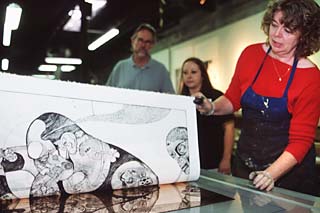

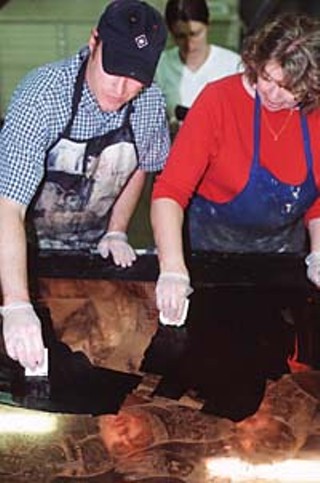

The myriad artists who work with Flatbed are not the only reason its prints are prized. Following in the footsteps of other print workshops in the United States and Europe, Flatbed is a collaborative workshop where artists, often from other disciplines such as painting or sculpture, collaborate with master printers. The process, as described by Katherine Brimberry, one of Flatbed's founders, "is exponential. You and the artist get more than you could alone."

Each of the master printers at Flatbed brings his or her own brand of printmaking to the process, and that contributes to a feel (rather than a look) embedded in many of the prints that Flatbed has produced through the years. In a collaborative workshop, the aim is to help the artist achieve his or her vision, not to make prints that look like they come from the specific press. That feel may be magnified with Flatbed because the press' partners choose the artists with whom they work, and the sensibility of the artists may dovetail or be heightened by a particular master printer's skills.

For instance, one signature quality of a Flatbed print is the way it stimulates the senses of vision or touch. This, more often than not, results from the way the plate was developed and the way it was printed, both areas in which the master printer is the most influential. (See "Technique Made Easy," p.34.) Another distinctive element in certain Flatbed prints is a kind of black that is more velvet than ink. It beckons and seduces; it is soft and mysterious. It draws you in and massages your senses. It is the black of sleep, safe and warm, in between dreams.

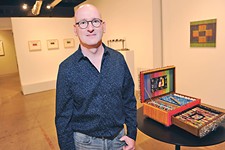

If, by these descriptions, you feel a sensibility at work in Flatbed, then you are connecting to the life of the print shop. Influential organizations are made so by the people who make them go, and at Flatbed, the founders are still running the show. Flatbed Press, the shop's original incarnation, was the brainchild of Mark Smith, and it started to coalesce a few years after Katherine Brimberry moved to Austin in 1983.

In the mid-Eighties, Smith was working as a corporate art consultant in Austin. It was boom time, and business was good. Brimberry moved to Austin with her husband, who hails from Vernon, Texas, the town in which Smith grew up. Smith took a look at Brimberry's prints and was impressed. They were "freer and more painterly" than most he had seen in Austin, and he placed them in corporate collections easily.

Smith, an artist and art historian by training, is an idea generator. He became interested in producing a "deluxe artist book," an unbound boxed suite of prints combining text and image, and asked Brimberry to be the master printer. As they talked about that project, other ideas came up and overlapped. Brimberry wanted a space where printers could come to work. (Printmaking is one of the more social artmaking activities, in part because the equipment is large, expensive, and frequently shared.) Both wanted to expand the audience for art and to create an informed audience for prints.

So Smith sold a beloved, restored 1950 Chevy for $5,000, and Brimberry took out a personal loan for $5,000, and Flatbed Press was born. The first incarnation started life in December 1989 with three presses, one of which Brimberry brought with her. One of the other two is still considered to be the largest press bed in Texas (a real draw for artists). It is capable of printing images as large as a sheet of plywood: 4 feet by 8 feet.

Now, fine-art presses are a bit like musical instruments. The lifetime of the equipment is longer than that of a human, so they end up having several owners. They are used to create art, but any art that comes out of them depends on the quality of the individual instrument and the skills and talents of the artist. Like a violin or piano, each press has a temperament that interacts with the sensitivity of the person using it. And with each "performance," the press acquires a patina that can only accumulate through time and use and which can somehow be felt in the next performance.

Flatbed was launched in the sleepy downtown that not so long ago was Austin. Located in an isolated leftover row of old warehouse and production buildings on West Third Street, just east of Lamar, the shop overlooked wild grassy fields spilling down to Town Lake just beyond the railroad tracks. It was a terrific space, large enough for the activities envisioned by the founders: a bright, long front room for hanging and showing prints and an expansive back room for housing the presses, creating limited-edition collaborative prints, and leading classes in both printmaking and connoisseurship. A year or so after Flatbed opened, the founders were joined by a third partner, Gerald Manson, who had been running Third Coast Press since 1982 and had occasionally been hired by Brimberry as a master printer when she needed help. When Manson joined Flatbed as partner, he closed Third Coast.

Each year, Brimberry and Manson published two to three artists, whose work was characterized by what Smith calls "Texas grit." In 1994, the shop opened a gallery as a way to get people more familiar with prints. With shows that changed every six to eight weeks and various other activities that drew artists and galleries to the overlooked strip, the out-of-the-way location transformed into an arts nexus. The good energy that Flatbed generated there continues in renewed form today, in venues such as Gallery Lombardi.

After a successful decade on Third Street, rising rents and lack of space led Flatbed to consider its future elsewhere. While the partners liked the "buzz and energy" of the creative community that had grown up around them, they had outgrown the 2,000-square-foot space and decided it made more sense to find someplace larger. For six months, they looked at spaces with a commercial realtor. Then they found an 18,000-square-foot building on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

At first, the space did not seem ideal. The ceilings were too low, the square footage too big, and refurbishing the space would require them to borrow money. But their friends in other print shops advised the Flatbed crew to get more space than they thought they would need, and the idea of being able to lease some of that space to others began to seem like an opportunity, perhaps providing Flatbed with more stability and allowing them to establish a built-in arts community. They signed a seven-year lease and, after months of renovation, began turning heads from downtown to East Austin.

In the new building, Flatbed started printing Texas artists that more fully reflected the art world today. After a time, they downsized their own gallery space, enabling others to take over, and a new synergy has formed around them.

Flatbed has three years left on its lease, but the partners are already pondering the next phase in the future of their organization. As of December 2002, Manson officially retired as partner, although he is still a welcome presence at Flatbed, where he makes his own prints and still works on print editions.

A few years ago, Brimberry was diagnosed with cancer, which gave her family and loved ones pause, but she has been treated for it and is now in remission. And having learned that being a landlord can occupy more time than you think, Smith is re-evaluating his goals. The two founders are not thinking of leaving Flatbed, but they are planning for Flatbed, like all good presses, to outlast its current owners. They have a vision of Flatbed eventually sustaining itself with a new generation at the helm.

Unlike most arts organizations, Flatbed was founded as a for-profit business. But in many ways, it is more like a nonprofit than a business. The third incarnation may be a hybrid -- perhaps a business with a nonprofit component. Smith talks about how hard it is to have a for-profit print shop. "You need a day job or subsidy," he says. "It is extremely rare to make a profit." One of the ways in which Flatbed is currently subsidizing itself is through a connection to the University of Texas: It rents exhibition space to the College of Fine Arts' Creative Research Laboratory and studio space to the art department's graduate students and faculty. Whether the ties with UT will grow is not known, although most successful collaborative workshops in the U.S. have ties to universities. But whatever Flatbed's next incarnation will be, it will be one that can continue when Smith and Brimberry have decided that it's their turn to retire. And in the meantime, the fine-art prints that the three partners have produced leave a record of the life of the organization. ![]()