Poetry in Emotion

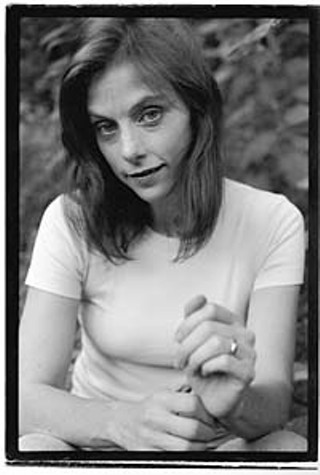

Why Katherine Catmull Is Onstage and Not in Class

By Robi Polgar, Fri., Oct. 6, 2000

It was a haunting image: a woman in an enormous white bed, in a beautiful white nightgown, ashen-faced, repetitively pawing at her cheek in an emotionally striking combination of terror and wonder. It was as if she could not recognize her face, and there were her hands, desperately trying, again and again, to understand the line of her unfamiliar cheek. Having just woken from a slumber of almost 25 years, she was incapable of comprehending that she was no longer the pretty, energetic 16-year-old putting a vase of flowers to rest in her parents' house. Here, in a foreign room, she had awoken as an adult woman -- with a different kind of beauty, a beauty of loss and wonder. In her mind, if not her body, she was still that perky 16-year-old, ready to make the marvelous transition to the rest of her life. Yet where did that life go? The unfolding tragedy of her slow comprehension that she was left behind, that she had missed her life, was made powerful and real by an actress who has undergone her own transformation into one of Austin's most sophisticated and highly literate performers.

The actress was Katherine Catmull, playing Deborah in the Subterranean Theatre Company production of Harold Pinter's A Kind of Alaska last season. "My dad," says Catmull, "he came to see [it]. And afterwards he said, 'That's the best performance I've ever seen you give.' And I said, 'Wow, thanks.' And he said, 'And it's the best performance you ever will give.' And I said, 'Uh, where did you get that?' And he said because he could not imagine a better role for me. He might have been right about that." Indeed, Catmull seems to have made a career recently of playing Pinter's mysterious women, who have full-blown lives locked inside private rooms, allowing only faint glimpses of their personal riches. In addition to Deborah, she has twice played Ruth in The Homecoming for Subterranean, and for The Public Domain she has played Emma in Betrayal and Rebecca in Ashes to Ashes, each to great acclaim.

"Pinter is just so extraordinary," says Catmull, who takes the question of what makes her an exceptional interpreter of Pinter's women and shifts it to what makes the playwright so great. "One extraordinary thing about him is, he was an actor, and he trusts actors, which most playwrights don't at all. Besides writing elegant, hilarious, needle-sharp dialogue, great words to say, he also gives you enormous room inside the roles. He does not straitjacket actors like most nervous playwrights: Now the character will explain herself and why she behaves this way; now the character will cry; now the character is happy -- emotional stage directions all over the place. Most playwrights do that -- I mean, the way Shaw puts in detailed physical stage directions. Pinter takes the straitjacket off, takes the stage directions out.

"Another extraordinary thing is that he writes as well for women as for men, if not better. He writes for women as if they were regular people with feelings, needs, passions, dark places. This, for example, is something David Mamet does not do; he writes brilliantly for men, but his women are opaque, they have no insides. So his masterpieces are his all-male shows. Pinter gives respect and freedom to two groups who don't really get a lot of respect and freedom in the theatre: actors and women. Which is marvelous. And then, on top of that, he is this brilliant playwright on every other level: dialogue, complexity, themes, structure, passion, wit, intelligence -- every way you could think to evaluate a playwright."

This is a typically well-thought-out -- and typically self-effacing -- answer from the highly literate Catmull, who brings a wealth of knowledge to bear on most questions pertaining to theatre or writing. She has the experience of working on more than 40 productions for a variety of local theatre companies since 1984. But she is also exceptionally well-read and holds a Masters in English Literature. (She's even been known to pen reviews for the Books section of The Austin Chronicle.) These qualities only enhance her gift as a wonderful conversationalist. (And I know whereof I speak. After she performed the title role in The Duchess of Malfi for The Public Domain, Catmull met me for a cup of coffee at Little City and we began what has amounted to an ongoing conversation about theatre, art, and life that's in its fourth year.)

Of course, pinning down such a cagey and smart rhetorician isn't easy. But after all her brilliant evasion about Pinter, she finally concedes, "I love to be in his plays." Then, with an afterthought that pries open the door to her own private room just a little, she adds, "I like those Pinter women because they are willful and not helpless and passive."

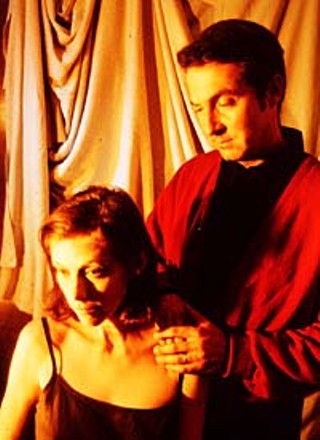

"She is the flat-out best interpreter of Pinter in town," says director Ken Webster, who is Catmull's husband and the artistic director of Subterranean, which she co-founded. "Kathy is a great dramatic actor as well as a terrific comedic actor." Webster should know. He has cast Catmull in an assortment of roles that would make the most seasoned actress jealous, from vapid traffic reporter and "primly perfect" Avery Bly in Wendy McLeod's modern morality play Sin to Pheenie in Heather McCutchen's Southern comic saga Alabama Rain to Janice, the vitriolic blond bombshell on the balcony in John Patrick Shanley's Italian American Reconciliation. Next up for Catmull: Jane, the unrepentant necrophiliac in Subterranean's latest effort, John Mighton's Body and Soul. As far as Webster is concerned, Catmull "has been making me look good as a director for 15 years."

Indeed, Catmull has been making a lot of Austin directors look good over the years. While Catmull may be best-known for her work with Subterranean, her résumé includes work for many local groups. She has performed for Frontera Productions' Vicky Boone in Wendy McLeod's searing suburban comedy The House of Yes and Elizabeth Egloff's fantasy love story The Swan, and this past summer she portrayed Li'l Bit in Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive, co-produced by Subterranean and the State Theater Company. While a standout in modern plays, dramatic and comedic, Catmull has proven herself equally adept at the classics and original work. I first had the opportunity to direct her when The Public Domain produced John Webster's Jacobean tragedy The Duchess of Malfi. In 2001, she'll return to her Jacobean roots, playing Goneril in The Public Domain's King Lear. Before that, however, she'll appear in Cyndi Williams' new play Fish, which opens at the Blue Theatre in November. Clearly, this is an actress who is very much in demand.

"When I have my playwright hat on, Kathy is one of my mainstays," says Williams. "How do playwrights write when they don't have wonderful actors to read their work for them? I can't imagine. Kathy is a great cold reader, but even more than that, she is perceptive and generous with her comments and questions about my scripts. She has the rare ability to probe my work without making me feel threatened or resistant."

Williams, herself a gifted actress with a long history on Austin stages, has worked with Catmull many times. "There are two things that always blow me away about Kathy, as an actor. Number one, she is just so damn intelligent. You hand her a script, and even reading quite cold, she has an amazing ability to find the truth of the character, instantly. Number two, she is always exploring, always questioning, always bringing something new and interesting to the table. I was so fortunate to play her sister in A Kind of Alaska. Having known her and having seen her grow as a person and a performer for so many years, I feel a deep and rather protective love for her. It was a privilege to get onstage with her and let that love out. It was also a painful challenge, because just the sight of her, looking so frail and strange in that beautiful white nightgown, brought me to tears, and to make the play work, it was important for me not to let those tears fall. We drank a lot of red wine together during that show."

One of the best things about a conversation with Catmull is that she will, eventually, answer your questions. I want to know how she goes about her work, and why the literary streak in her is so strong. Instead of answering directly, she gets me into another tangential, literate conversation, this one about the international double puns of Samuel Beckett, especially those in the names of his characters. Beckett, who wrote in French first, then translated his plays into English, named two characters in Endgame "Clov" and "Hamm." The puns? Pronounced with a long "o," Clov sounds like a spice you'd stick into a ham. (Ouch.) And knowing that the French word for nail sounds similar to Clov makes the image a Hamm(er) banging incessantly on the Clov. (Ouch again, but in the opposite direction.) Such is the duality of those characters' relationship, such is the pun, such is a conversation with Catmull.

After all that, though, and more, we get to the bottom, or near the bottom, of what makes her such the literate actress, why she pursued English for so long, and how that has informed her acting. "Actors ought to have a huge background in literature," Catmull weighs in forcefully, "and in how to read literature. Not so much in the theory and history, [but] knowing how to read. What does it mean that [words] are next to each other? I think they're similar: reading and acting. That's why English Lit: because I love reading. I'm good at reading."

I try to delve deeper: Why so good at reading? "I don't know why," she starts, then adds, "but I think I am a really good reader." She starts to deflect the conversation from its focus on her -- "Oh, don't put that in! I'm sure there are a million ... I think part of it is ..." -- then, finally, the door opens. "There are talents in music or talents in math, or something, and I think I have a talent for language," she says. "But also, starting really early, my mother used to read me John Donne, when I was six or seven. I think she was doing it because she was bored staying home with a bunch of small children. So she would sit me on her lap and say, 'I was in love with him before I met your father,' which really shocked me when I was seven. When I got older, I looked at his dates under the picture and I thought, 'Oh, she was just kidding.'" Catmull laughs, then continues. "I still have an anthology called Master Poems of the English Language that she gave me when I was seven. An old paperback of hers in which she checked the poems that she thought a seven-year-old would like, like the 'Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner,' some Robert Frost -- poems that were accessible to a child to a certain extent. Still, that's pretty unusual. So I never got scared of [poetry]. But it's taught so badly in schools sometimes -- poetry -- that people just form blocks against it, and I never did.

"I would teach a sophomore class in poetry where [the students] were all, 'Oh my god, now it's the poetry unit,' and nobody wanted to take it. And some teachers would go at it like, 'Let's dissect rock lyrics' or something like that, but I always thought that was backwards. I would start the first day with a really difficult-to-read poem, a poem that right off the bat the language is really hard, like a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins. I'd write it up on the board and everyone would be thinking ..." Catmull grimaces for her former students and laughs. "And then we'd spend a class or two just taking it apart. And then, I think, it helped give them confidence. 'Oh, okay, now I see how you read poetry.' And most poems we read would not be nearly so difficult to parse as that."

Catmull approaches plays the same way, seeking out recurring images or considering the choice and juxtaposition of words. In Pinter's The Homecoming, she noticed the difference in the way Ruth spoke of her time in America with her husband Teddy, using words like "desert, dryness, rocks, images of lifelessness." But when she spoke of England, the words got wetter, more boggy, "images of wetness and muck and dirt are both more disgusting and yet more full of life -- sexuality and life."

Of course, in addition to her well-honed critical sensibilities (and high affinity for puns), there is a personal quotient to her character work. Ruth's blossoming into a fecund, powerful matriarch attracted Catmull: "She just made me happy. Odd, since she is a crazy, terrible person. But I just felt so jolly and alive both times I played that part. That's what the play is about from Ruth's perspective, I guess: coming alive again after being dead, desiccated, for years. Feeling juicy again after years and years in the desert."

Catmull has always brought such intelligence to her work, but there is something, well, juicier, in her approach to acting. Actor David Stahl has worked with her, on Big State Productions' version of Our Town in 1990 and 1991, in Subterranean's Raised in Captivity in 1998, and in The Public Domain's Ashes to Ashes in 1999. "When we began rehearsal for Our Town, I was rather intimidated, she was so good and so serious. We didn't talk much to each other about personal things; whenever we did talk, it was about the characters. I learned something from Kathy that years of training never taught me about approaching character. That is: She never judges the characters she plays. In Raised in Captivity, she and I played brother and sister, Sebastian and Bernadette. Again, her ability to [not judge] her character made Bernadette a much more believable person in what seemed to be an unbelievable situation. Bernadette was very funny, but also she left one with that heartbreaking feeling. I think it's that deep well within Kathy at work."

"One of the most useful things anyone ever told me about acting was, 'When your character is tense, put her tension somewhere other than where you put yours,'" explains Catmull, winding her way, slowly, toward something more personal. "If you put tension in your shoulders, make your character have tense hands or jiggly legs or whatever. Otherwise you will make yourself tense, which will jam everything up onstage, just make everything more difficult. For similar reasons, the roles I like playing are ones with different problems and issues from me -- characters whose problems are that they are too brash and ballsy, or who don't give a damn about destroying lives as they follow their dreams." Catmull reminds me of something that happened when we worked on The Duchess of Malfi. "I asked you to put back in some lines you'd cut, all the lines where she was cranky and mean and commanding," she recalls. "You'd only cut them for space, I think, but I was so afraid the cuts left her really, really nice and sweet, when one of my favorite things about her was that she wasn't -- that besides being brave and noble, etc., she was also capable of snapping at people over apricocks.

"Characters who have the same problems as me are more difficult and not quite as much fun to play. There's this constant struggle to deal with things I don't really want to deal with in my own life -- although it can still be very fulfilling. Right now I am rehearsing two characters, one obsessed with guilt over something she can't change and that wasn't entirely her fault, and one who is defiantly proud of the fact that she sleeps with dead bodies. They are both great parts, but the second one's more fun."

It's just after the final performance of How I Learned to Drive, Catmull emerges from the dressing room at The Hideout in what appears to be starched, new hiking gear: an Oxford shirt, pleated khaki shorts, thick socks, and a brand-new pair of boots, which she has been breaking in for a few weeks in anticipation of a much-deserved vacation to Yellowstone. It's a rather jaunty, outdoorsy look -- a neat, action-oriented costume that suits the smiling, generous, and genuine actress, who would rather extol her cool new boots than talk about herself.

But it's easy to forget we're trying to do an interview and to settle into an engaging, multi-faceted conversation with Catmull. She's smart, disarming, and charming. On the balcony of the Stephen F. Austin Hotel bar, we chat about all sorts of things, but especially her upcoming trip to Yellowstone with Webster and her family: five siblings (she is the eldest), her parents, and assorted in-laws, aunts, and uncles. The Yellowstone trip is both restorative and something of a reminiscence: Her actor grandfather, Joseph Catmull, was a park ranger during the summer months, when he wasn't acting or teaching acting at the University of Utah. There are reminders on the trip of what appears to be a theatrical lineage -- a sense that, with so much theatre in her family's past, there was almost no way she could avoid becoming an actress herself.

Catmull's grandfather was a gifted Shakespearean actor. He was renowned for his interpretation of King Lear, although Catmull never saw him act that part, and has only a hazy recollection of him performing at all: playing Santa Claus once. "But we had a record, an LP, of him doing bits of King Lear with other people. It was like an abbreviated King Lear. I don't know whatever happened to that record, but it was great." Her grandfather also fought, and lost, the battle to avoid acting. "He had kind of a thing for my grandmother. She was in her dad's acting troupe." The troupe, the Farnsworth Players, traveled around the country and when it found itself stuck in Rupert, Idaho, the couple met. After that, her grandfather became something of a constant presence around the troupe. "Finally, my great-grandfather, O.L. Farnsworth said, 'Why don't you be in one of the shows?' So [my grandfather] got into acting because he had a big crush on grandma. He never really liked acting; he wanted to be a lawyer. He tried really hard to go to law school, but they kept dragging him back into acting." When the head of the department at the University of Utah offered him and his wife free room and board if he'd stay and act, his fate was sealed.

"Mother's side of the family also worked in amateur theatre and cabaret," says Catmull, taking care to give family members on both sides their due. "My mother's father worked briefly for George M. Cohan, as a sort of secretary of something." Catmull smiles: "My mom says, 'Oh, he makes too much out of that: I think he held his horse for him once.' It's not like when I was a kid I thought, 'Oh, all this theatre in my family, I must ... I will go forward in it.' I never had thoughts like that. It just worked out that way." Was she doomed, like her grandfather? "Doomed." She laughs. "Yes."

"I have no idea why I started, actually," she says. "I wrote for the school paper when I was a sophomore (yes, yes: nerdy), and I asked to write a story about the final dress and opening of a school play. And it was exciting. So, though plain, extremely shy, and slightly pudgy still, I auditioned for the next play -- Dark of the Moon -- and was cast as the Fair Witch.

"I acted through the rest of high school. We did ridiculously excellent plays, very badly -- Pirandello, Lorca, Giradoux, Ionesco, Synge. Actually, the Lorca we did decently, considering I was playing a 70-year-old. Anyway, I determined not to be drawn into such a hopeless career in college. I was very academic, and theatre isn't very -- at least acting isn't very. I studied English Lit, with a minor in languages, first at the University of Chicago and then at Reed College [in Portland, Oregon]. At Reed, to fulfill my fine arts requirement, I allowed myself one acting class. The teacher asked if I would like to play Nina in The Seagull the next semester, but I shied away. Not doing that! No!"

At graduate school at the University of Texas, she says, "I started to feel slightly disenchanted with academics. And whenever I went to see my brother Joe in a play -- he was in the UT drama department -- I would feel all stirred up and wild with envy. I took a seminar called Jacobean Literature in Performance, something like that, which had the radical (for English departments, back then) idea that you can learn a lot about plays by performing them. We worked up several scenes, sometimes the same one from different viewpoints. One of the ones I did was [from The Duchess of Malfi], the duchess's proposal scene to Antonio, which I did with my friend Bill [Friedman]. The Royal Shakespeare Company had a little tour over here, a five-person Measure for Measure, I think. And one of them, Julian Curry, agreed to come look at our scenes and talk to us. And he really liked our Malfi scene and told me and Bill that if we liked, he would get us roles in this Macbeth he was going to do at the Santa Cruz Shakespeare Festival that summer. No pay. In fact, we'd have to sign up for summer school to be eligible; still it was very flattering and exciting. So we did."

The rest is textbook Austin artist: "I came back and did 'Tis Pity She's a Whore on campus with a slightly mad British visiting prof and a bunch of ex-Winedalers. Got my MA and decided not to go further for my doctorate." She stayed in Austin and "auditioned badly and unsuccessfully for lots of things around town." She met director and future husband Webster when her friend Bill talked the self-described "gloomy, pessimistic" actress into auditioning for Webster's production of Sexual Perversity in Chicago: "Ken was directing and saw on my résumé that I had the same address as Bill. He assumed we were lovers (we were just housemates) and decided despite my crummy audition that maybe it would work out, somehow, if he cast us as lovers. No one else had auditioned well either, so he cast me."

Since that production 16 years ago, Catmull has acted in over 40 productions for a variety of local companies, growing more and more comfortable onstage, more precise, stronger. "Every play -- like those early plays, I think back, 'Oh my god, I had no idea what I was doing' -- but each one you learn some new thing. The second one I did with Ken was Kennedy's Children, which is all monologues and talking to the audience. We did it at Liberty Lunch. I was really uncomfortable talking to the audience the first weekend. I'm looking at them; they're looking at me -- Aaaah! I can't pretend I'm somewhere else! But then I realized, it's like this great power. I had this great power. It was a huge revelation: that I have power over the audience. That is such an obvious thing about theatre, but it was a big revelation to me."

What makes an actor truly exceptional, offers Catmull, "is some good combination of riskiness and control. It's a balance of those two things. You feel that you are really on the edge, and the audience can feel you are on some kind of edge, but at the same time you actually have control when you are out there. That's really cool when that happens, that's the best.

"You're so much more personally involved in theatre, that's why it's far more exciting to watch theatre than movies when it's going well. When it's going badly, it's much more distressing. It's incredibly painful watching acting going really, badly wrong. It's incredibly thrilling to watch it go really, really right. It's hard to watch Nicolas Cage and be thinking, be worrying -- and not just worrying for him, but worrying for me, too -- 'In just a minute I'm going to feel really bad because you're going to be horrible.'" She laughs, then continues: "You never have that worry with Vanessa Redgrave. All the time she's thrilling you, you never have any worries. It's hard to explain. She's so open; also, she's so surprising. You know she has that long, aristocratic -- long bones -- she's not girlish at all, but she often plays really girlish characters, charmingly, openly. She's amazing. I love her."

This description of Redgrave brings back an image of Catmull in that great bed, her long fingers stroking her face, girlish yet aristocratic, authoritative yet helpless. The contradictions are completely in keeping with Catmull's approach to acting: boldly searching out roles that aren't "nice" or easy; a willingness to get into the "muck" of a character's darker, rougher parts, while simultaneously creating characters who are almost luminous in their beauty. She haunted as Rebecca in the Ashes to Ashes I directed -- strong enough to bear a nightmare of Holocaust proportions, yet serene, even pure, as she sat, so still, on a darkening stage. She was searing in The Public Domain's staging of The Possibilities last spring, playing characters who faced impossible odds, did horrible deeds, and had horrible things happen to them, but who still chose hope over despair. Throughout her career, it seems that Catmull has embraced the life in her characters, no matter their situation, finding beauty in horror, poetry in adversity, humanity everywhere. Onstage, she is poet-like, capable of creating passionate, deeply wrought characters, even with the smallest flick of her actress-imagination. Or perhaps she is a poem herself. One that at first glance seems daunting and deep, with hard edges and difficult passages but, which with a little time and effort, proves to be smart, endearing, funny and, finally, ever so accessible. ![]()

Body and Soul runs October 5-28 at Hyde Park Theatre, 511 W. 43rd. Call 444-4553.