All the Way to State

The UIL One-Act Play Festival

By Sarah Hepola, Fri., May 12, 2000

The stage may be empty, but that does not keep Matt Humphrey from staring at it. The Bowie High School senior is temporarily held captive by its vacancy, its blank-slate quality, its anything-could-happen cachet. Any minute now, the stage will not be empty anymore, and an official with the University Interscholastic League (UIL) will make the announcement Humphrey is waiting for: which schools are going to the state one-act play competition and which schools are going, well, home. It's a simple yes or no question, really. Will Bowie advance or not? Will he be hugging neighbors and slapping high fives? Or will he sit, stony-faced, while his stomach collapses? Until he finds out, time is a buzzing, three-headed beast that is certainly not on his side. Forget the hours spent memorizing lines, forget the weeks eaten up with rehearsals (Friday nights and Sundays, too!) and the 5am wake-up calls for festival competition and the desperate, last-minute changes: That part was fun. This is the hard part. Waiting. And waiting. The lead in Bowie's production of Not About Nightingales, Matt is a tall, angular 18-year-old with bright, honest eyes and lashes many women would say are wasted on him. He has acted in at least 20 shows at Bowie, and in a few days, he'll begin directing one. Not About Nightingales, however, is his favorite. "You know, there's never been one rehearsal I didn't like," he says, cheery and polite. Cheery and polite and sort of distracted. "Not one." Last year, when he was in the one-act play competition, Bowie fell out at regionals, just shy of the state contest, and Matt is anxious not to repeat the experience. "We were devastated," he remembers, playing with an orange Slinky. Distracting things like orange Slinkys become of utmost importance in the hour or so lag time between the end of the last performance and the announcement of who moves to the next level. "That was so tough." A play advancing to state might not sound like a big deal, but it is tremendously important to Matt, to his fellow cast members, and to many of the 18,000 students in 1,200 schools across the state who participate in one-act plays every year. Let Matt tell you: "This has had more impact on my life than anything else so far."

Like most kids in this room right now, like so many of the students who have taken part in one-act in its 74 years of existence, Matt Humphrey is focused on making it to state, on being in one of the eight shows in his school's 5A division to perform at the University of Texas in Austin, on hitting the top of the largest high-school drama competition. Anywhere.

Matt starts to say something, then stops.

The stage is no longer empty.

Arriving at Bowie at 4:30 on a Wednesday afternoon, I see students spilling into the parking lot, making plans to hook up later, climbing aboard one of the yellow buses lining the curb. Just watching them, with their spangled butterfly clips and baggy pants, makes me seize up: I wonder about the clothes I am wearing, the way I should talk, the awkward in between-ness of my age -- an adult to them but not to me. Inside, the halls are emptying out -- nothing but blue lockers and the smell of industrial cleaner -- leaving the one-act play cast, just getting dressed for rehearsal, with the whole, huge place to themselves. It's a familiar feeling, like a lived-in groove, all those late-night rehearsals when the halls rang with silence. You could go to the cafeteria wearing your costume, skipping all the way if you felt like it, safe and comfortable, for once, inside the building.

For this year's competition, Bowie is mounting Not About Nightingales, a recently rediscovered Tennessee Williams play about the wretched living conditions in a Depression-era prison. Despite the "one-act" in the contest name, schools rarely compete with true one-acts. Commonly, they use shortened versions of some of the stage's longest works, severely trimmed to meet the contest's strictly enforced 40-minute time limit. As with bringing a robust, meandering novel to film, characters must be snipped, peripheral stories must be sacrificed, lengthy speeches must be compromised. A version of Hamlet that I once saw began, "Alas, poor Yorick, I knew him well," a line that occurs a good three-quarters of the way through the melancholy prince's tale. Nightingales, which ran over three hours when it premiered at the Alley Theatre two summers ago, is now clocking in at a lean 39 minutes, leapfrogging from climax to climax while still managing to make sense. Mostly.

Directing the production are Kris Andrews, who came to the school from Pflugerville two years ago, and Bowie's grande dame of theatre, Betsy Cornwell, who has run the program for two decades now. Like the world's best teachers, they neither talk nor act the way you expect teachers to ("Your diction sucketh," Cornwell notes to the cast), and they maintain a steadfast devotion to a job you couldn't pay people enough to do, although it would be nice to see someone try. As coach, confidant, and even parent, they work out of that sometimes dangerous gray zone in which they must balance being a friend and maintaining authority, cutting loose and taking work seriously. If they are successful, they can create a sacred space where students will crawl out of their comfort zones, take risks, and make startling things happen. For 20 years, Betsy Cornwell has been doing just that, and as evidence of her success, the department has grown to include a staggering 375 students, who participate in nearly 18 plays every year. What Betsy Cornwell has never done in those 20 years, however, is bring a one-act play to state.

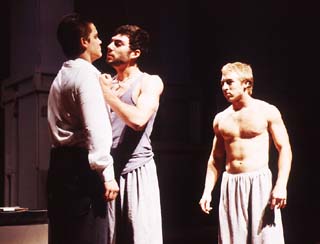

Eventually, the Bowie students begin to trickle onstage. Jordan Arredondo, a senior with close-cropped black hair and a dark, scruffy beard, announces his entrance with a cartwheel, bouncing lightly on his toes, all coiled-up energy waiting to spring. He has the unmistakable swagger of a popular high-school boy, and it's no surprise he was voted Mr. Bulldog -- the Bowie contest to determine the best-looking senior. When Sean Harrison walks onstage, still talking to someone in the wings, Jordan finds his opportunity -- hiyaw! -- pouncing onto his back. Without blinking, Sean leans over to one side and tosses him off, the way mothers continue conversations as their babies grab handfuls of hair and earring. At another time, it might be met with a withering look, or a sharp indictment -- "Boys!" -- but until rehearsal begins, it is tolerated, watched with amusement even. Together, Jordan and Sean run through some of the moves they've been learning lately: Along with a few other cast members, they've been trying to nail the dance to 'N Sync's latest video "Bye Bye," which they offer as nerve-settling distraction during the tedious backstage downtime of competition. Sometimes, Chris Velez whips out the harmonica and plays some Dylan songs to pass the time. Even when the curtains are closed, they're still performing.

Jordan's pinwheeling adolescent rowdiness, however, is focused in his performance. As Butch O'Fallon, brutish leader of Cell Block C, he is all machismo and rage -- grabbing someone by the collar, spitting in his face, letting screams rip raw from the back of his throat. In his dreams of the future, as hazy and cinematic as any 18-year-old's, Jordan sees himself living in New York, a struggling actor coasting by on odd jobs and bit parts ("like Joey on Friends"), hungry and beaten and close to calling it quits until -- Bam! Discovered. If he stares into the distance, he can see it, like a drifting perspective point at the end of a road. But at this moment, there is only one thing on the road, and that is UIL one-act play.

"I'm all about the Big W," he tells me later, meaning, of course, the win. "Maybe it's the testosterone, I don't know." Having traded in sports two years ago to devote himself fully to drama, this is some of the only competition Jordan gets, and he is sinking his teeth in deep.

He was in the cast last year, when they didn't advance from regionals. "That night, I said: Next year. Next year we're going to state."

At district competition, on April 1, Bowie High School takes the first step there by advancing to area.

A week later, on April 8, I am curled up in the surprisingly comfy auditorium chairs of Pflugerville High School, waiting for area competition to begin. Having nothing better to do, I attempt to handicap the competition using a complicated, utterly unreliable algorithm based on: each company's UIL history (have they been to state? how many times?); the director's history (which I rarely know, so it might as well not be included); the pathos, amount of screaming, and opportunities to stretch (i.e., handicap, cancer) allowed by the play; and the perceived "artsiness" of a school's name -- for instance, Dallas' Bryan Addams tanks in this category, while Bowie (as in David!) tops the scales.

Any one-act play veteran knows certain shows make it to state every year: Children of a Lesser God, The Diviners, The Crucible. Often, that's because the scripts provide opportunities for young actors to flex their chops, and the students seize those opportunities. It's the same principle at work in the Academy Awards, where the Oscar consistently goes to the actor playing someone dying or saddled with some disability. Another common trait of successful one-act plays is their generous use of atmospheric fog. Lots and lots of fog. If success in one-act has anything to do with fog -- and often it seems so -- Bowie is a shoo-in this year. Believe me, Not About Nightingales has fog. Before the show began at district competition, the school's hissing machine was issuing so much fog through cracks in the curtains that it appeared as though something backstage was on fire. When the curtains opened, the fog billowed out into the first two rows. Of course, it's a grand, dramatic visual, with all the white clouds backlit by blues and reds, meant to evoke the unbearable heat and stench of Klondike, the prison hole where corpses lie at the beginning -- limbs intertwined, mouths agape -- a glimpse at the play's eventual tragedy.

Last week, Nightingales advanced from district with Austin High's production of Reckless, a bravely dark comedy by Craig Lucas which follows one woman's careening, 15-year path to happiness. At district, Reckless dominated the awards, taking the lead actor award for Travis Fowler and the lead actress award for Dorothy Harrigan, a young woman that Austin High director Billy Dragoo will later describe as "the finest actor I've ever seen." Watching Dorothy at this competition, I am again floored by the effortlessness of her performance -- not just her dopey, flighty delivery but the way she ages herself and manages to make me doubt the one thing I know about her: that she is in high school. A teenager? No way. These are the moments at one-act play that are most shocking -- that someone so young, and presumably inexperienced, could convey such depth.

The Bowie performance, on the other hand, is cursed. During a fight scene, Matt smashes his fingers into a brick wall, so that they start dripping blood. Worse than that, though, is that Jordan and Matt's poignant goodbye is interrupted with a swift, swiveling flash and a piercing alarm. Whoop! Whoop! Whoop!

"Warning!" a robotic voice announces. "A danger has been detected in the building. Please leave the building immediately."

"Do you think this is part of the play?" whispers a woman nearby.

Onstage, the actors -- Matt, Jordan, and female lead Virginia Kull -- are frozen in place, mid-handshake, mid-sentence, mid-cry. The room is suddenly prickly and hot. After a moment, Matt (his fingers still dripping blood) begins again, only to be cut off.

"Warning!" Swift, swiveling flash.

"I don't think this is part of the play," the woman adds. But no one moves from their seats.

"Warning!" it threatens, three times, maybe more, the actors locking eyes, waiting for it to pass. The tension grows so unbearable, I almost want one of them to drop their guard, turn to the audience -- "Okay, can we start this again?" -- just to end this bizarre, awkward stalemate. But they don't.

They wait for the alarm to stop, and when it finally does, they finish the play. It turns out all that fog, atmospheric though it was, tripped the smoke alarm.

At the end of the day, however, the beleaguered Bowie cast is rewarded for its trial: This time, it sweeps the awards, with medals going to Jordan, Virginia, supporting actor Matt Gee, and, collectively, to all the prisoners. Matt Humphrey, his fingers wrapped in a bandage, wins Best Actor.

Bowie High School heads for regionals.

"It's rare that you have so many boys that can act," says Shirley Arredondo.

"And that look so good," adds Donna Kull, to which both women laugh.

Donna is the mother of Virginia, the sweet-faced, ivory-skinned redhead who plays Eva Crane, a woman so desperate for work that she accepts a job at a prison, only to fall in love with Jim, one of the inmates. Donna has not missed one level of competition, and for the regionals at Baylor University, she is joined by Shirley Arredondo, mother of Jordan, an elementary-school teacher who missed last week only when a convention kept her out of town. In five months, their children will load up a car and ship off for the next phase of life, but in the meantime, these moms are soaking up their last few chances to be a spectator -- however silent -- in their children's everyday lives. A year ago, Donna and Shirley were in the same place: watching their children, then juniors, compete at regional one-act competition with The Tempest, an extravagantly staged version of the Shakespeare play, complete with actors on stilts and a turning, curtained set. That year, Bowie looked on longingly as Westwood's Much Ado About Nothing and The Woodlands' Caucasian Chalk Circle (both schools back for the competition this year) continued to the state meet. This year, the women are crossing their fingers that things will be different.

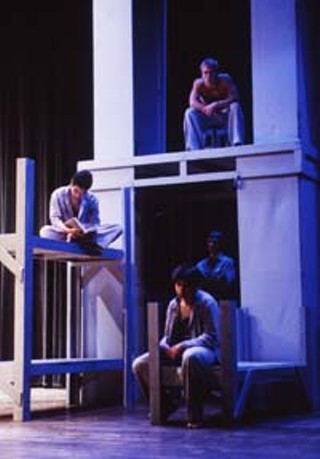

At five o'clock, when the Nightingales cast comes onstage to build their set, it seems at once too soon and about time. Like all one-act contest productions, Bowie's stage will be created from what is known as a unit set, a standard collection of flats and pylons and two-step stairs, like giant gray Lincoln logs that can build just about anything. In this case, they create an impressive, two-story prison, complete with bunk beds and benches. To build it, boys move across the stage carrying each other on their shoulders, a breathtaking performance in itself, but slowgoing, with snags. Baylor's unit set isn't exactly fitting right, and when boys jump up on the bunk beds, the whole contraption sways ominously. Backstage, Donna's daughter Virginia has misplaced one of her costumes, and she is hurrying around the stage, all business. More nervous than any of them, however, are the parents watching it from the audience. It makes for sharp inhales and crunched brows, because whatever happens today is out of their control. Despite the fact that they are programmed to do so, they cannot leap to their children's defense, fight off the enemy, or even stand nearby, screaming their support from the sidelines. In fact, Jordan's mom decides she is entirely too close to the stage.

"Jordan knows I'm wearing this bright yellow dress," she says, picking up her purse. "I don't want to do anything to mess up his concentration." And then she moves off, burying herself several rows back.

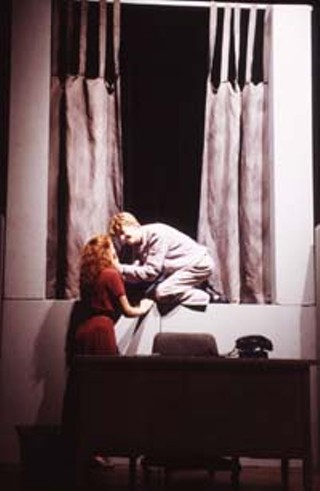

After the performance is over, and the set is being dismantled and cleared away, Donna will exhale a shuddering sigh and place her hand lightly to her chest. "It gets harder to watch every time," she says. In the show, Virginia must give in to the advances of the lecherous warden, played by T.J. Linnard, in order to keep from being thrown in prison. He angrily drags her back to the office, ripping off her dress and thrusting his body angrily into hers. "When they took Virginia off this time," Donna will say later, "I thought: Where are you going with my baby?"

But the fear wears off, and when it does, it is replaced by pride, radiating off her like a blistering sunburn. She stands up and turns to make eye contact with other parents sitting behind her. They share thumbs-up signs and encouraging nods of approval. When Shirley Arredondo comes back down the stairs, the two women walk to each other, relieved that it's over, and hug: They nailed it.

Lou-Ida Marsh has been a one-act play judge for 16 years and has judged 105 contests. In UIL terms, that makes her a legend; in Lou-Ida terms, that makes her an old biddy. Now that the last show of the regional contest is over, Lou-Ida is somewhere in the building, scribbling out her award choices -- eight honorable mentions, eight all-star cast selections, best actor, and best actress, divvied among 62 students in six shows -- as well as the decision on which schools will advance. It's a daunting task, so to score each play she uses the contest's standard guidelines, which allot 60% for acting (with categories such as voice, characterization, movement, ensemble, motivation) and 40% for directing (set, lighting, sound, make-up, costume). But she knows that judging productions isn't really a function of math; she's the first to admit it's all subjective. "Honey," she tells me, her expressive voice rising and falling as if she is reading a poem, "a different judge may call a contest a different way. I may call a contest a different way on a different day."

The relativity of it all is a sticking point for some, and Lynn Murray knows that all too well. A deeply Southern gentleman with white hair and a beard that recall none other than Colonel Sanders, Murray has been the contest director for some 30 years now. He knows all the complaints; he's the one who takes the phone calls. Although he occasionally tinkers with the idea of using a panel of judges, there's simply not enough money and not enough bodies to go around. "If it were a utopia, we'd have a panel," he admits. "And we'd have three teachers in every classroom, too."

As Lou-Ida is racing to finish the awards, the students are biding their time in the auditorium. Out of their costumes, they are almost unrecognizable. The girls, so recently saddled with dowdy frocks or period dresses, wear clunky black heels and clothes that cling to their figures, their faces still gloppy with stage make-up. Boys who so recently appeared 40 years old, dying of cancer, father of four, come close enough to reveal a constellation of pimples on their cheeks, a flash of silver in their smiles. These figures, so large and vital and strong onstage, seem suddenly small, vulnerable. They seem like kids.

Mostly, the schools stick to themselves, each taking over its own small section of the auditorium. The students talk to parents, share Game Boys, give each other shoulder rubs. In the Bowie section, parents sit a cautious two rows behind the students. If approached by their children, they report on the day's other shows, which the Bowie cast missed while they were backstage rehearsing. The Woodlands' Shadow Box was good, they say, full of great acting and nicely directed. Klein's Beauty Queen of Leenane was harrowing and creepy, although it's rare to see a four-person cast advance to state. Westwood's Much Ado About Nothing was even sharper than it was the previous week, when Bowie competed against them at area. The students nod thoughtfully, soaking it in, gauging their chances. "It's only one person's opinion," a mother reminds her son. "You just never know."

But in a moment they will. The stage, so recently empty, is empty no longer. Everyone in the room stops talking, almost at once.

Stan Denman, a Baylor professor who also happens to be the person who judged Bowie at the district contest, will announce the acting awards from smallest to largest. The cast hopes, for example, that Matt's name is called for an award. However, they don't want it to be called too soon. Last would be nice, actually. Matt's name called last would be very good.

"Whatever happens in the next 10 minutes," Stan Denman announces, "you still had a good time." All down the row of cast members, knees are bouncing compulsively, fingernails are being chewed. "If you came here to win today, the odds are against you. If you came to learn today, the odds are in your favor."

The second award is announced: Honorable Mention, Matt Humphrey.

Names are being called way too fast. Jordan is called to the stage soon after Matt for an Honorable Mention. Virginia receives an All-Star cast award, but that means Best Actor and Best Actress will go to other schools. The company members begin to trade glances, sometimes worried, sometimes consoling. Behind them, the parents cluck tongues but are otherwise silent. One of the actresses leans her head on her boyfriend's shoulder, and he begins to stroke her blond hair tenderly. Clapping for every name called, the Bowie actors all smile that crooked, heartbreaking smile of disguised disappointment. Then Stan Denman makes official what they already, in their gut, suspect: The advancing schools are Klein High School, with The Beauty Queen of Leenane, and The Woodlands' The Shadow Box.

And like a Band-Aid being ripped off, it is suddenly, strangely over.

The state meet is swarming with people. Schools with names I've never heard of -- Humble, Whiteface, Louise, Comfort -- crowd Bass Concert Hall in their team T-shirts, flirting and gossiping while their directors reunite with old colleagues to talk shop. I invited the Bowie students to join me here, but tonight is their prom, and they have things like corsages and boutonnieres and the perfect color of nail polish on their mind. Regionals was a disappointment, yes, but they're moving on to the next thing. The Monday after the competition, they were already back in the theatre, working on more one-acts -- this time directed by seniors, and just for the school's, and their own, enjoyment. I go to the state meet by myself -- in fact, I go every year, not so much out of nostalgia as out of sheer appreciation: for the talent, the passion, the way the kids set their sights on something -- all the way to state -- and follow through on it. They're not holed up at home, sneering and bitter and terrified to fail. They go after what they want, full-throttle, without irony and without fear. And if they don't make it? They deal. I'll be honest: Sometimes the shows aren't all that great. But often they are. Often they are amazing, and when they are, my heart starts pounding and I forget where I am and I can't shake it for the rest of the day. I love it. I don't know why.

I lied. I do know why. The reason I love going, the reason I return every year, is because it inspires me. I would watch 50 shows, back to back, just to feel the way my heart pounds when it really gets going. It's not that it makes me want to be young again or that I mourn my wasted youth or anything like that. It's that it makes me want to take risks, makes me want to embrace things, makes me want to fall in love. I may not be an actor, I may not even want to be, but like so many other people who went through one-act play, theatre is in me, and through me, in my laugh that is too loud, and the way I use silly accents, and the way I am drawn to people who do the same.

The stage may be empty, but not for long. ![]()