El Quemado

After 40 Years, José Francisco Treviño Is Still Exploring Art

By Mary Jane Garza, Fri., Dec. 31, 1999

When José Francisco Treviño was around 15 years old, his art teacher and mentor at Fulmore Middle School on South Congress gave the young artist all his oil paints and old brushes. The teacher, Mr. Bozart, was leaving town for other opportunities and wanted to make sure that his student used the talent he clearly saw within him. It was a fateful gesture, one that turned Treviño firmly down the road to a career in art. Soon after, the young man produced his first painting, which he still has. Now, more than 40 years after producing that first artwork, the prolific Treviño is enjoying a retrospective of his art at Mexic-Arte Museum. With more than 130 paintings, drawings, and sculptures covering Treviño's work from his high school days to the present, "Raices Sin Fronteras -- A Retrospective" is the largest exhibition of this kind the museum has ever presented. Thanks to the artist's careful preservation of his work, Mexic-Arte was able to create a unique opportunity for art lovers to see the development, interests, and personal life of an artist over a span of several decades.

Born and reared in Austin, Treviño clearly remembers the city of a half-century past. Downtown was different then. Sixth Street had bars and stores for the working class and for those who came in from the outlying communities for supplies. As a kid, Treviño would hike to downtown, sometimes walking into the building that now houses Mexic-Arte, which used be a furniture store.

"My art reflects experiences that I had then and that I have now," Treviño noted in a lecture he gave at the museum in November. "I reflect back and see things and compare the past and now. I see the changes, and in my art I try to reflect that. I have been drawing since I was a kid. I remember always drawing [from a young age]." While at Travis High School, he won an award for another oil painting, and the teacher would sometimes let him teach the class. Upon his graduation from high school, though, his formal art education stopped.

With an intense desire to produce art, Treviño then learned by observation, going to galleries and studying different artists' techniques and approaches. Through trial and error, he taught himself their techniques. The styles of some of the European masters he studied during that time period are evident in the works he created -- for example, in the exhibit is a painted profile of a man inspired by Rembrandt. "That's the way I learned," explains Treviño. "By copying."

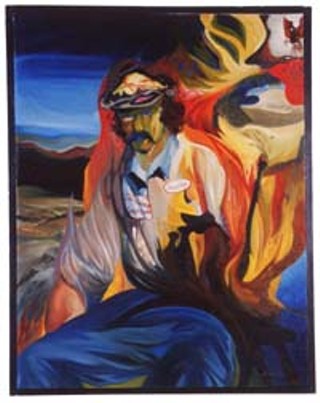

The Austinite also followed the example of the masters in painting from the world he knows. Like the famous French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Treviño began painting bar scenes, street scenes, the everyday worker in his environment. He even incorporated his personal life into his work. In one painting, the artist depicts his difficulties with alcohol, with two men situated around a table offering advice to a third, who doesn't seem to be taking it. In another, the self-portrait Uno de Los Quemados, Treviño depicts himself in the work uniform of the job he had at the time, sitting in a landscape inspired by his trips to Mexico and partially engulfed in stylized flames. Here Treviño chronicles that period of his life when he was part of a controversial Chicano art collective, Los Quemados. Made up of such prominent artists as Santa Barraza, Carmen Lomas Garza, Cesar Martinez, and Amado Peña, "the burned-out ones" referenced the artists' nonconformist, political attitude toward the established art world of the time, when it was difficult for many of them get exhibited in mainstream institutions. "I paint myself into my art a lot," explains Treviño. "And I think it is because I'm still trying to figure out myself."

Treviño's life changed profoundly in 1973; that's the year the artist met his future wife, Modesta. She bought one of his paintings after taking a class on Chicano art history in college, and it was natural that the admirer and the artist would come together, deeply influencing each other. Modesta also became active in the local Latino art scene, and she and José have been involved in many exhibitions, conferences, and organizations throughout the years.

"I feel my life changed into a different phase when I met my wife," says Treviño. "She showed me a lot of things I didn't know about, and my art starting reflecting that. At that period, we did a lot of traveling into Mexico and Guatemala and saw a lot of things. I started seeing things in a different way because of her experiences. Our two experiences together kind of gelled to create this new vision I had on my part." Treviño pays homage to his wife in his art -- but not always with sweetness. A large humorous painting of Modesta titled Little Miss Self-righteousness is part of the Mexic-Arte exhibit. Done in the 1970s after the two had a disagreement, it shows Modesta with exaggerated features, the mood of discontent captured clearly in her face.

In one of his self-portraits, Treviño has placed himself walking down road with the hills of Ixtapa, Mexico, in the background. He explains the painting and the enduring relationship he still has with his wife this way: "I've always felt my life as if I was on the road. And I used to do lots of roads in my paintings after I met my wife. This road represents the road of life to me. The time I am awake I'm going through a journey in life and this [little fairy-like creature] represents my wife. When I met her, she said, "This way.' And she still says that."

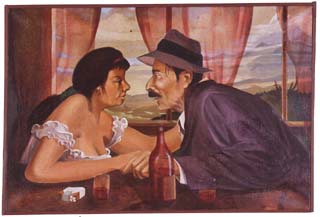

With the large number of works on display in the Mexic-Arte retrospective, the different styles and techniques that Treviño has used are available to see. One technique that he uses often is glazing -- putting layers and layers of oil paint thinned with linseed oil on the canvas so that the painted object projects depth while revealing the layers underneath. It works well in interior scenes with glasses and bottles, to give them a sense of translucence. In Treviño's painting Mira te Voy a Decir, the beer bottle in the foreground and especially the red sheer curtains over the window in the background provide excellent examples of this technique. Not only do the curtains draw attention to the seated figures, but they frame the blue sky perfectly, giving an even greater depth to the composition.

Another technique that is a constant in Treviño's work is one he calls "reality breaking away" or "cyberspace." For it, the artist paints a gauzy and spotty membrane-like substance over a portion of a piece. The effect is like focusing your vision on something so that your peripheral vision is like spots or grains of reality. As you move away from the subject, you can't see anymore until everything disappears, reality disappears.

Treviño takes a developmental free-form approach to his art. "I have the imagery in my mind and the composition to start, but sometimes I don't have the ending" he says. "It's like we take a trip without thinking where we're going. We just want to take a trip, so we get away and take the trip and go where we feel like going. Well, I just start painting. I start with the faces, then I move away. Like I didn't really intend to have someone sitting inside a bar, but that's what came out. And sometimes I start something and I don't get finished for a long time."

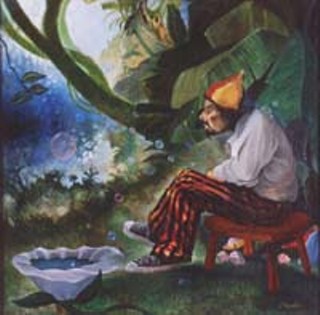

The work that's perhaps the best evidence of Treviño's self-professed slowness is the exhibit's largest painting, The Peephole, which took the artist more than 20 years to finish. He began in the late 1960s with the face of a man, then progressed to the checkered pants he's wearing. Looking sort of like a court jester, the old man is sitting in deep contemplation, out deep in the woods. "I put all these bubbles and dots around him, so he's like materializing and fading away. For some reason, he's looking a certain direction, so I didn't know how to finish this. I opened the reality here and made him looking into cyberspace, looking into the cosmos, this hole in the reality. It would be like standing around daydreaming -- we're looking into some focal point, our mind is somewhere else -- so that's what he's doing. He has his moments of contemplation."

After creating art for so many years, Treviño realizes that the more techniques and styles the artist learns, the more freedom he has to express his ideas in any style he feels like. "It's like a musician that knows how to play a lot of instruments," he says. "He can play classical or he can play ragtime or comical little things. I don't like to be just standard. Like the title of my show, there's no border. I can't be contained in one thing because it all interests me. It's part of my spirit, not being contained. I know we are all contained in a sense, but in my art I kinda fight it because I don't like to be put in one category. When the artist stops exploring, he becomes stagnated. He doesn't excite anymore." ![]()

"Raices Sin Fronteras -- A Retrospective" is on display through January 14 at Mexic-Arte Museum, 419 Congress. Call 480-9373 for information.